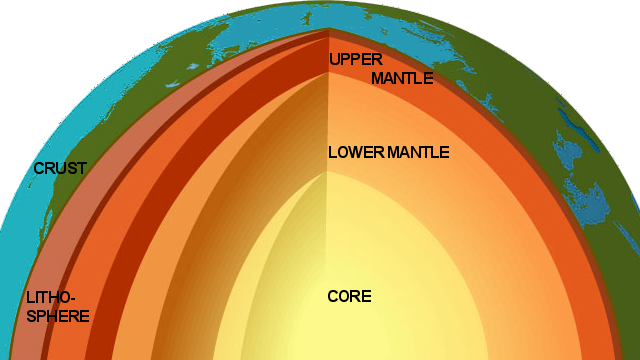

Water is part of Earth’s very definition as a planet. Clouds of water fill its atmosphere, oceans cover most of its surface, and groundwater is found everywhere underground. For the last century, geologists have been tracing the influence of water deeper and deeper into Earth’s interior. During the last year, whole oceans worth of water have been found in the mantle, hundreds of kilometers below the crust. And a paper in today’s issue of Science traces water’s influence all the way down to an important boundary inside the Earth, the top of the lower mantle.

The study, by a team of five scientists led by Brandon Schmandt (University of New Mexico) and Steven Jacobsen (Northwestern University), combined high-pressure experiments on minerals with high-precision seismic observations to argue that large amounts of melted rock—magma—exist far deeper than the magma feeding volcanoes on the Earth’s surface. Their research involved the transition zone, the bottom part of the upper mantle between 410 and 660 kilometers deep.

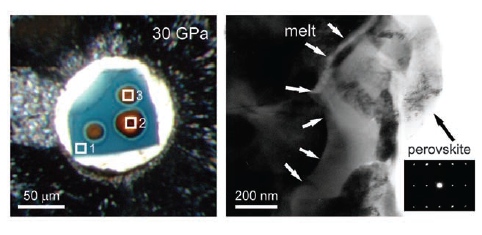

A paper earlier this year in Nature reported that ringwoodite, the most common mineral in the transition zone, can contain more than 1 percent of water inside its crystal structure, a significant amount. Schmandt and Jacobsen’s team did an elegant experiment to show what would happen to ringwoodite as it hits the bottom of its comfort zone at 660 kilometers depth. At that depth ringwoodite breaks down and forms two new minerals, neither of which can hold as much water. They laser-heated tiny spots in a water-bearing ringwoodite sample, forcing it to form the two higher-pressure phases, and showed that the water expelled during this process formed a thin layer of melt around the edge.

Next, they analyzed the high-quality data from the great USArray seismic experiment, a 10-year project that has been mapping the mantle beneath the United States with a set of hundreds of seismometers, moving from area to area like a doctor using a stethoscope. The behavior of earthquake waves down at the base of the transition zone matches what would be expected from large areas of melt. More precisely, these would be large areas in which a small fraction of the rock, consisting of the hair-thin spaces between mineral grains, is molten. Just as dry sand behaves very differently when it has a small amount of water between its grains, so too does the rock of the mantle. Wet sand is stiffer than dry sand, but wet mantle is the opposite—softer and more pliable. The slippery layer in the uppermost mantle that allows the tectonic plates to move about—the asthenosphere—that’s wet mantle.

The picture Schmandt and Jacobsen’s team present in their paper is one in which the stirrings in the mantle, caused by plate tectonics, move large volumes of rock into and through the transition zone. As these move down through the 660-km level, most of the water they contain is released and left behind. A similar reaction is already known to take place as rock moves upward through the upper edge of the transition zone, leaving water behind. This new paper puts the lower boundary into the story too, suggesting that the transition zone tends to retain water over geologic time. It may even function like the asthenosphere higher up in the mantle.