If you imagine the San Francisco Bay as a bathtub, sea level rise means the bathwater is rising. A new study published today in Science Advances finds the tub is sinking too, and in some places, more than others.

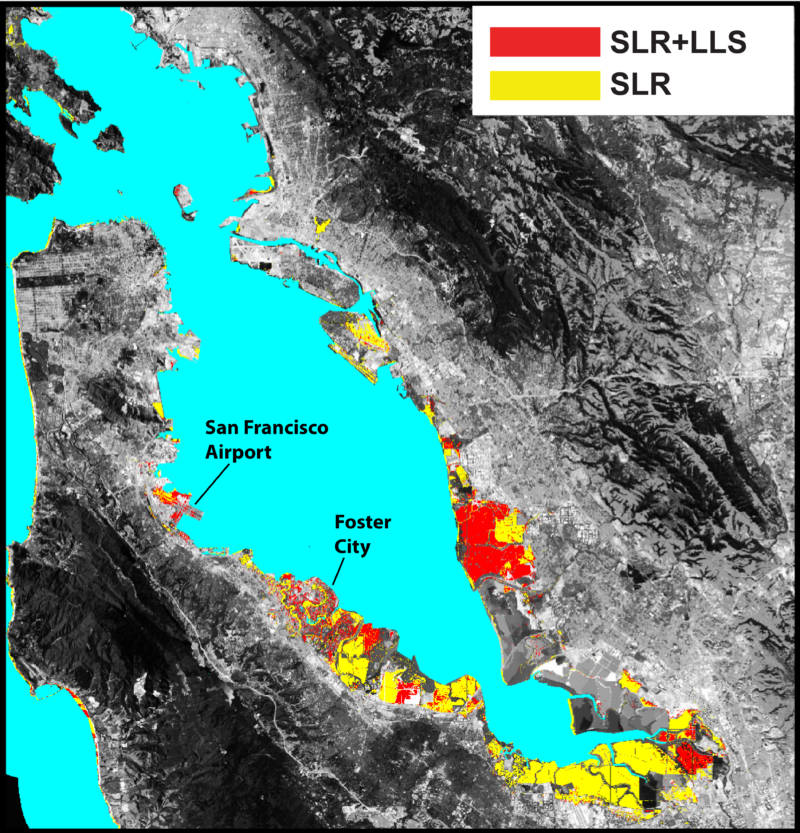

Where Bay Area cities have built on landfill or newer mud, that land is compacting, and sinking faster than other places. This subsidence is a problem for, among others, Foster City, Union City, San Rafael, and the land around San Francisco Airport.

“The northwest corner of Treasure Island is subsiding really rapidly – half an inch or so per year,” says UC Berkeley geophysicist Roland Burgmann. He’s a senior author on the study and worked with Manoochehr Shirzaei, a former postdoctoral fellow at Berkeley, now at Arizona State University.

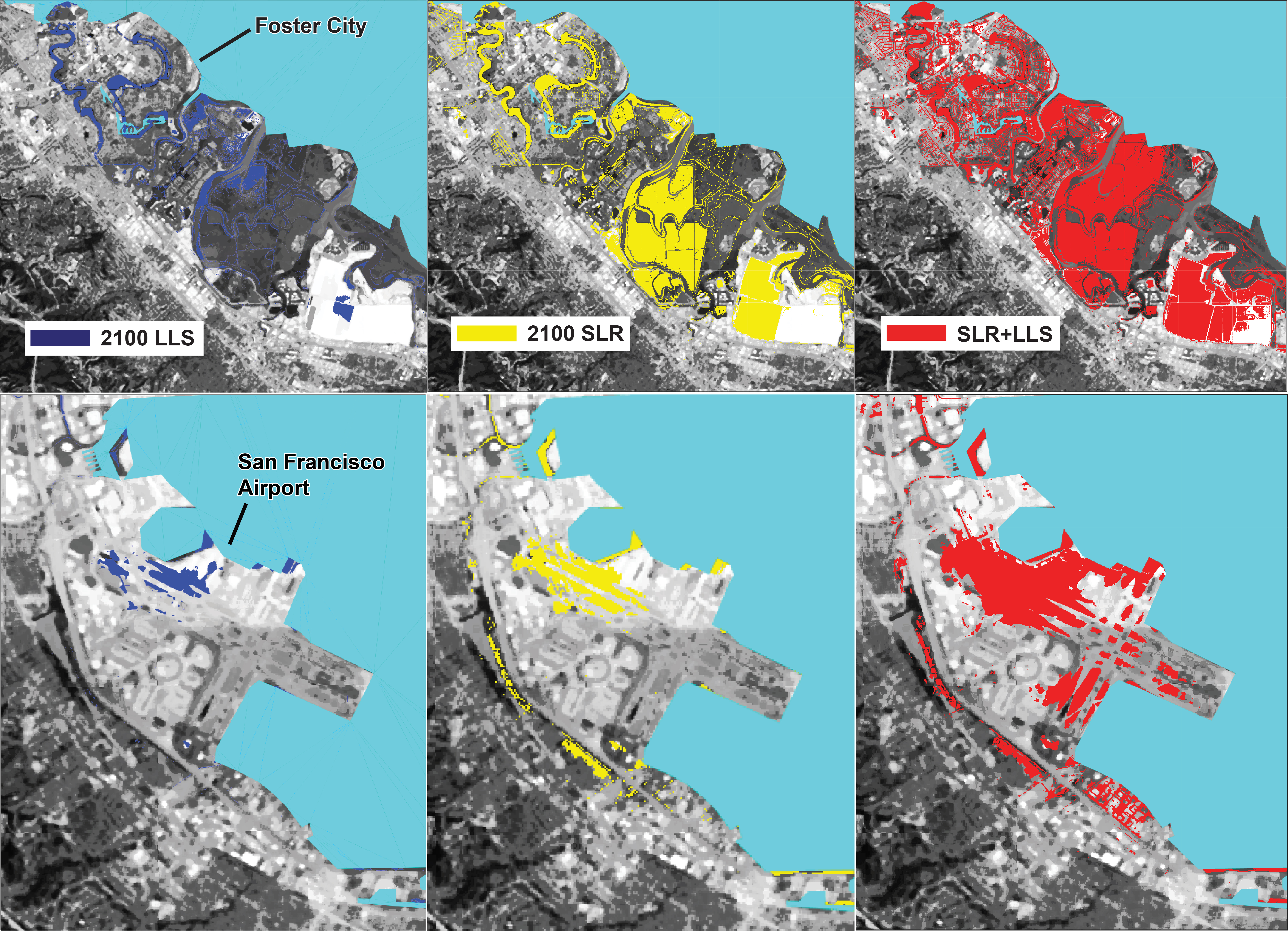

Burgmann and Shirzaei used an ultra-precise satellite radar system to map, for the first time, Bay Area land loss with exacting resolution. By combining projected land loss with sea level rise, the team concludes that by century’s end, 90 percent more land could be at risk of flooding than from sea level rise alone.

“These maps show where we should be pretty much underwater all the time on average,” Burgmann says. He cautions that the work only addresses flooding related to sea level rise and subsidence – essentially, what happens when you raise the level of bathwater while lowering the tub itself.