What kind of medium could this be? Stumped, the greatest physicists of the 19th century came up with a wild idea: Imagine that all of space is filled with an imponderable medium called the ether. What it was, no one knew. Its sole purpose was to allow light to propagate. With hindsight, we could call it magical stuff. Even as attempts to find it failed, physicists would not let go. The alternative, having light propagating in empty space, sounded even crazier.

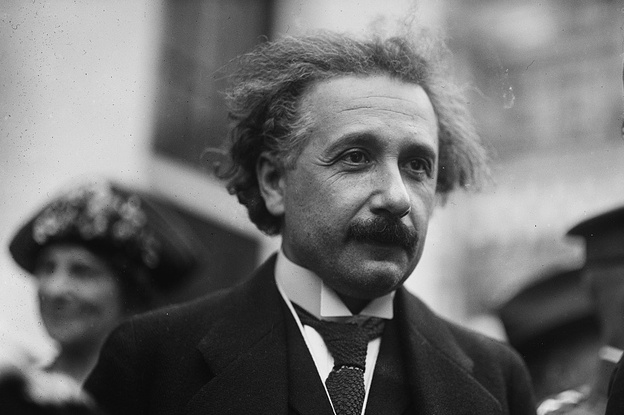

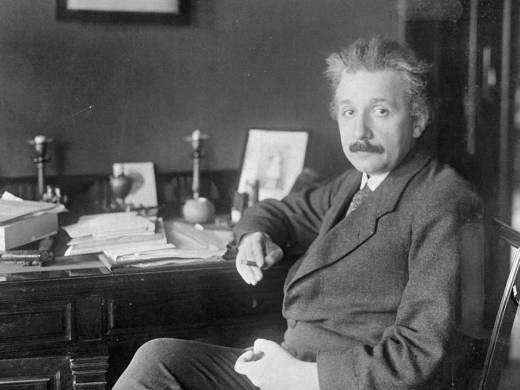

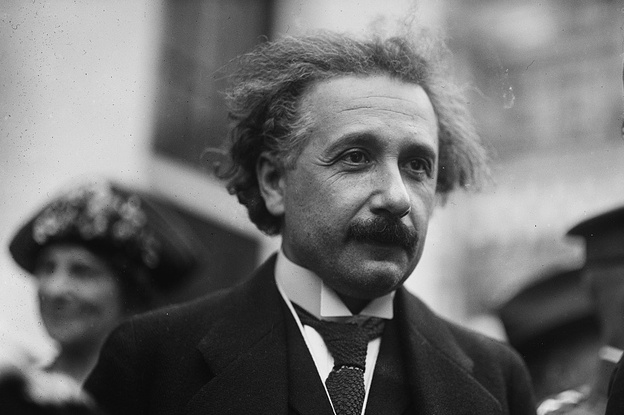

Enter Einstein. In 1905, he proposes his special theory of relativity, whereby he singlehandedly destroyed the notions of absolute space and time, and the need for an ether. According to the theory, now one of the greatest success stories in the history of thought, the notions of space as a rigid stage at which things just happen and of time as a steadily flowing river, are just an illusion caused by our myopic view of reality. And it’s all light’s fault.

Space would only be a rigid stage and time would only be a steady river if light could travel from Point A to Point B instantaneously. (That is if light traveled with an infinite speed.) But it doesn’t. Our illusion is corrected once we incorporate the fact that light has a finite speed of propagation, even if it’s so ridiculously high. (In fact, it is its enormous value that makes our illusions so persistent and convincing.) Once the correction is factored into our studies of motion, everything changes. An observer at rest that measures the length of a moving bus will obtain a different result from the passengers in the bus. To her, the moving bus will be shorter. If she also saw a clock attached to the bus, she would notice that the seconds pass slower for it than for the watch on her wrist. Amazed, she would conclude that moving objects shorten in the direction of their motion and that moving clocks tick slower.

The effects, called length contraction and time dilation, become more pronounced as the speed of the moving object approaches the speed of light. Remarkably, Einstein also showed, in a second paper he wrote that same year, that no object with mass could ever reach the speed of light. Mass itself grows with speed and becomes infinitely large at the speed of light. Only light itself, or another entity with no mass, could travel at light speed. And by the way, all this is perfectly consistent with light traveling in empty space. No ether. Light is like nothing else in the cosmos.

The effects, called length contraction and time dilation, become more pronounced as the speed of the moving object approaches the speed of light. Remarkably, Einstein also showed, in a second paper he wrote that same year, that no object with mass could ever reach the speed of light. Mass itself grows with speed and becomes infinitely large at the speed of light. Only light itself, or another entity with no mass, could travel at light speed. And by the way, all this is perfectly consistent with light traveling in empty space. No ether. Light is like nothing else in the cosmos.

In 1915, Einstein expanded his theory to include motions with variable speeds (i.e., with acceleration). His theory of general relativity, arguably one of the towering achievements of the human intellect, imprinted the plasticity of space and time into the fabric of the universe itself. Now, the presence of any material object (or merely energy) could bend space and alter the flow of time. Space and time became literally pliable. For example, a light ray from a distant star would be deviated from a straight line as it passed by the sun. (It does as it passes by you, too, but the bending is so small as to be literally immeasurable.) In 1919, two expeditions were sent to test Einstein’s prediction of this phenomenon. Their data, despite bad weather and measurement issues, were conclusive: Einstein was right.

Later on, Einstein’s prediction for the flow of time was also confirmed: Time slows down in strong gravity. A clock on the top of the Empire State Building ticks faster than one on the ground. But the effect is tiny: If you were to spend your lifetime on top of the Empire State Building you would lose 104 millionths of a second. Even more fun: In a 79-year lifetime, the cells in your brain age faster than those in your feet by about 45 billionths of a second.

Einstein was the first to apply his ideas of space and time plasticity to the universe as a whole. In 1919, he devised a model for the entire universe: a static, spherical, perfectly symmetric cosmos, with matter homogeneously distributed everywhere, reflecting a mix of Platonic perfection and of Ockham’s Razor. That first model, even if wrong, became the inspiration for all the work on modern cosmology that followed it, including the now widely-accepted Big Bang model, whereby the universe emerged from an event 13.8 billion years ago and has been expanding and cooling ever since. Black holes, gravitational waves, all of this follows from Einstein’s general theory. Oh yes, and so does the accuracy of your GPS, which needs elements from both the special and the general theories.

Remarkably, all this relativity stuff was only one of Einstein’s playgrounds. The other, his muse and demon, was quantum theory. Next week, I’ll take it up from here, and explain why Einstein got his Nobel prize for his ideas on the nature of light (being both a wave and a particle) and not for relativity. And why he was haunted by the quantum ghost to the end of his life.

Note: As this article was being edited, we learned of Stephen Hawking’s passing. An uncanny coincidence, he was fond of telling that he was born on the 300th anniversary of Galileo’s death; and now, he passes away on the 139th anniversary of Einstein’s birth.

Stephen Hawking was one of those rare life heroes who shone above all of us as a beacon. Not just as a brilliant physicist whose contributions to our understanding of the universe and of black holes will remain forever in the annals of science, but also as a life-loving, amazingly resilient person. He had the generosity of heart to share his knowledge and inspire millions of readers around the globe. His love for life must be celebrated and remembered by all of us, scientists or not.

The effects, called length contraction and time dilation, become more pronounced as the speed of the moving object approaches the speed of light. Remarkably, Einstein also showed, in a second paper he wrote that same year, that no object with mass could ever reach the speed of light. Mass itself grows with speed and becomes infinitely large at the speed of light. Only light itself, or another entity with no mass, could travel at light speed. And by the way, all this is perfectly consistent with light traveling in empty space. No ether. Light is like nothing else in the cosmos.

The effects, called length contraction and time dilation, become more pronounced as the speed of the moving object approaches the speed of light. Remarkably, Einstein also showed, in a second paper he wrote that same year, that no object with mass could ever reach the speed of light. Mass itself grows with speed and becomes infinitely large at the speed of light. Only light itself, or another entity with no mass, could travel at light speed. And by the way, all this is perfectly consistent with light traveling in empty space. No ether. Light is like nothing else in the cosmos.9(MDAxOTAwOTE4MDEyMTkxMDAzNjczZDljZA004))