Slow-moving earthquakes along the San Andreas Fault can trigger bigger, more destructive quakes, according to researchers at Arizona State University.

A new study published in the journal Nature Geoscience suggests that this slow movement, which can last for months at a time, calls into question current models of earthquake forecasting that may be underestimating the risks.

Many scientist have believed these gradual movements provide a safe and steady release of energy, helping to reduce the risk of a huge quake. But the new findings indicate that the motion of this continuous creep is in fact not steady, but rather consists of episodes of acceleration and deceleration.

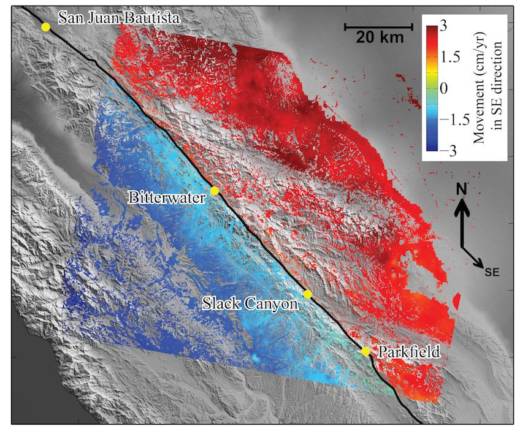

These stop-and-go movements along the central section of the fault line can place a lot of stress on the locked segments along the fault’s outer portions, according to Manoochehr Shirzaei, co-author and assistant professor at ASU’s School of Earth and Space Exploration.

“We found that movement on the fault began every one to two years and lasted for several months before stopping,” Shirzaei said in a statement.