This weekend, members of the Winnemem Wintu tribe wrapped up a 300 mile trek, from the mouth of the Sacramento River north to Shasta Lake. Dozens of Winnemem, indigenous activists and allies walked, ran, biked, boated and rode horses along the way. The event, called Run4Salmon, is part of the tribe’s plans to change the course of history for endangered Chinook, once plentiful in this part of the world.

“We’re here … in an effort to wake the people up to what’s happening to the water systems here in California and also to restore our salmon,” said Winnemem Chief Caleen Sisk.

Winter-run Chinook salmon have been blocked from native spawning habitat on the McCloud River above Shasta Dam for decades, but Sisk wants to change that. Run4Salmon, now in its third year, is meant to raise awareness about the region’s imperiled salmon.

Chinook were once a dietary staple for the Winnemem, but after European settlement in the 19th century, overfishing, dredge mining, and dams on the Sacramento River and its tributaries caused salmon populations to plummet. Today, climate change is expected to warm waters, making Northern California even less hospitable to salmon. Many populations appear on the Fish & Wildlife Service’s endangered species list as either threatened or endangered. Winter-run Chinook face “immediate risk of extinction,” according to a 2017 report from the conservation group California Trout and the University of California-Davis Center for Watershed Sciences.

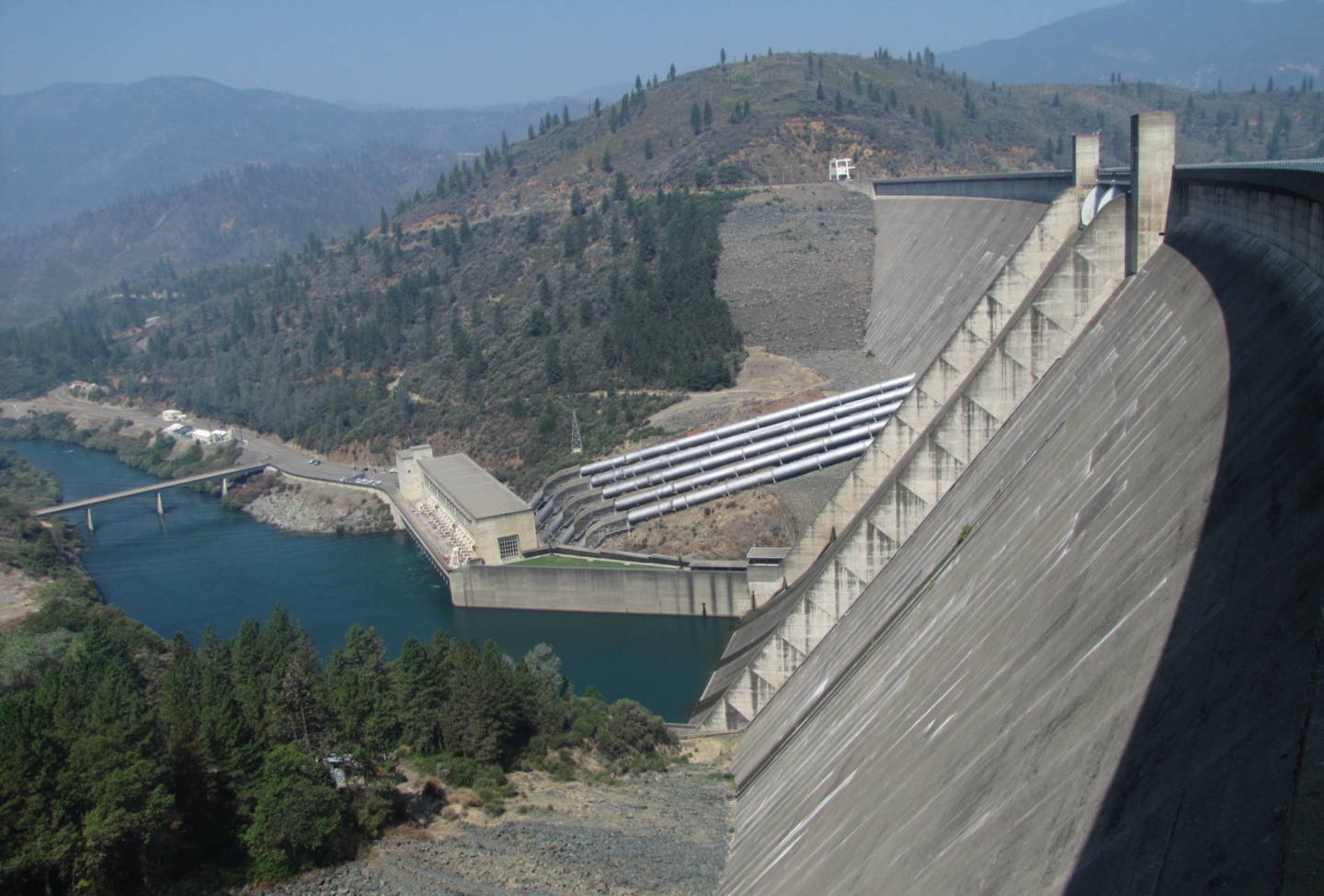

Shasta Dam is perhaps the biggest obstacle to salmon restoration in historically Winnemem territory. The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation built the dam just north of Redding in the 1940s to store water for California’s growing cities and agricultural industry. Today, it’s a linchpin of the state’s sprawling water system and creates California’s largest reservoir. The Bureau of Reclamation plans to raise the 602-foot dam another 18 ½ feet to store an additional 630,000 acre-feet of water.