Reporter Molly Peterson conducted a 5-month investigation into heat in California, in partnership with KQED Science. In a series of stories, we will examine who’s vulnerable and why, and what it will take to protect people who are vulnerable to heat illness and death at home or on the job.

Last year, as a Labor Day heat wave descended, Claudia Hernandez was trying to pry open the windows of a house in San Francisco, from 400 miles away.

That weekend, San Francisco hit 106 degrees, an all-time record. After two straight days topping 100, Hernandez, who lives in Orange County, pleaded with her godmother, Colleen Loughman, to open her windows and let a breeze through.

Like most in the city, Loughman’s home lacked air conditioning. “A fan, an old school fan, that’s all she had,” Hernandez said. “And her windows were like maybe one-eighth open.”

Talking with her 82-year-old godmother, Hernandez felt something was off.

“You could hear that she was, I don’t know, like, drained,” she says.

Colleen Loughman died the next day, in the house her parents had built. She was at risk because her aging body couldn’t acclimatize to intense, fast-arriving heat. She was vulnerable in her home, without a way to cool down. And though she was loved, she was isolated.

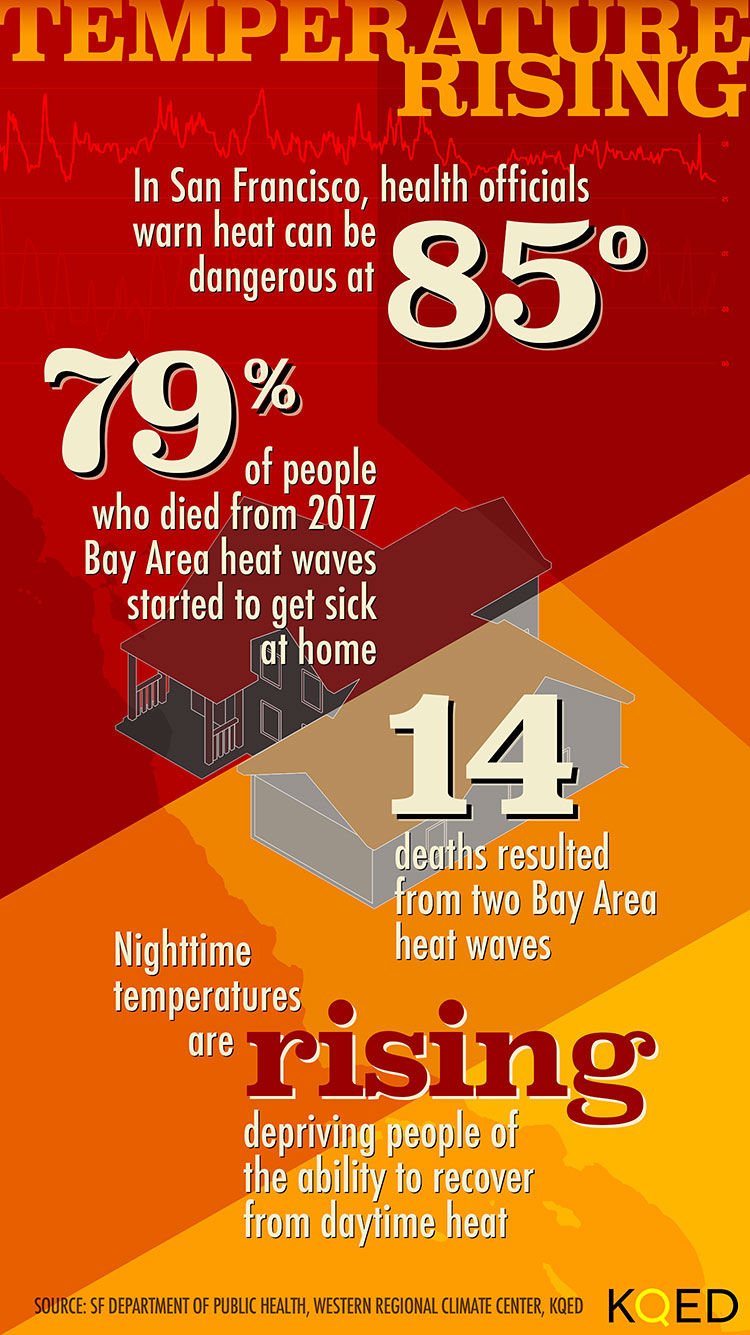

In June and September of 2017, two heat waves killed at least 14 people in the Bay Area, and sent hundreds more to the hospital.

San Francisco was caught off guard, says the city’s deputy director of public health, Naveena Bobba.

“What we were seeing is really a huge health emergency,” she says.

The past five summers have been California’s hottest on record.

Even in cool, coastal parts of the state, heat, a sneaky and growing threat, is now one of the state’s top climate-related public health risks.

Why Older People Are At Risk

Last September, Loughman wanted her windows closed because she had been having lung trouble, and she feared smog and smoke would make it hard to breathe. She had heard air quality alerts on the news, issued by regional regulators.

Spiking heat worsens asthma and lung conditions and raises risks for older people in particular.

Older people have to work harder to stay cool, says Dr. David Eisenman, who directs the Center for Public Health and Disasters at UCLA.

“When your body normally gets hot, it cools down by transferring heat inside its core out to the skin.”

For most people, sweat cools the body well, but not for older ones. “They have a less effective ability to sweat,” he says.

Older bodies hold less water than younger ones, putting older people more at risk in a heat wave. And older people are less sensitive to becoming hot and thirsty.

Over several hot days, all of that means physiological heat can build up without relief.

And Colleen Loughman wasn’t prepared for that in her foggy Parkside neighborhood.