In recent decades, San Franciscans have embraced the reborn Embarcadero waterfront as kind of front yard, and at noon on a weekday it crowds with tourists, skateboarders, entrepreneurs and other locals. But underneath wheels and feet, three and a half miles of seawall is cracking and crumbling, vulnerable to rising waters or a major earthquake.

Proposition A would authorize a $425 million general obligation bond to shore up the aging seawall, most of the money needed for initial repairs to its weakest sections.

If voters approve it, this bond would be merely the down payment on a multi-decade strengthening project, aimed at the acute risk of earthquakes and the creeping risk of rising seas.

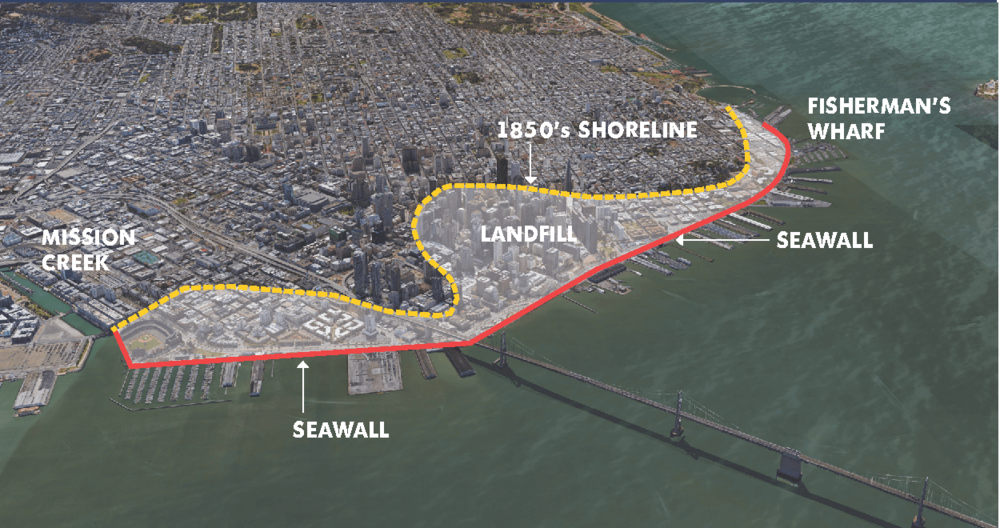

One hundred and sixty years ago, the city’s natural shore was a muddy crescent, arcing nearly a half-mile inland from the current waterfront. The Transamerica Pyramid, had it stood at that time, would be waterfront property.

Those mud flats became a problem after the Gold Rush. Ships, whose return passage to home ports were funded only with prospectors’ dreams, were abandoned in shallow water. Some became saloons, or makeshift hotels. Running a ship aground intentionally helped build up sediment and bolstered legal land claims.

“It was just a mess,” says Lindy Lowe, resilience program director for the Port of San Francisco.

To tame this wildcat scene, the state of California began filling in coastal flats in 1878, and over 40 years pushed the waterfront farther into the bay.