Update May 14: A little more than three months after this story first appeared, the State of California and more than a half-dozen fishing and conservation groups sued to stop Westlands Water District from working to advance the Shasta Dam expansion project.

Original post:

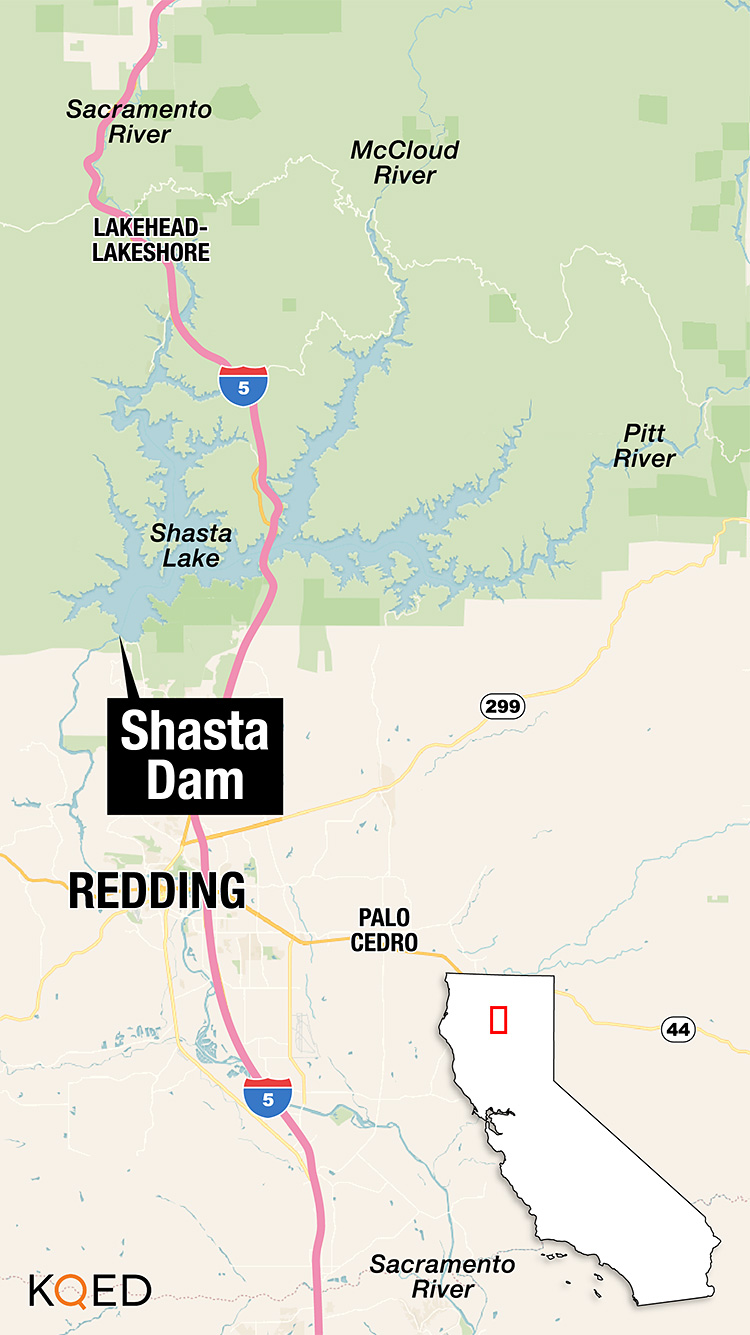

The Trump administration is laying the groundwork to enlarge California’s biggest reservoir, the iconic Shasta Dam, north of Redding, by raising its height.

It’s a saga that has dragged on for decades, along with the controversy surrounding it. But the latest chapter is likely to set the stage for another showdown between California and the Trump administration.

Last fall, crews already had drilling rigs in place, taking core samples from the earthen banks around the 600-foot dam. That process was part of testing to see if its World War II-era foundation can support additional bulking up of the dam.

Taller Dam Means a Bigger Reservoir

This is what the federal Bureau of Reclamation calls “preliminary construction” work. For now, that’s all they have funding for, but the Trump administration is keen to press on with a $1.3 billion project to add more than 18 feet to the top of the dam, which is already taller than the Washington Monument. That would increase the size of the reservoir, Shasta Lake, by 14 percent.

“We’re extremely confident that there’s a lot of momentum behind this right now,” says Don Bader, area manager for the reclamation bureau, which operates the dam.

“We’re extremely confident that there’s a lot of momentum behind this right now,” says Don Bader, area manager for the reclamation bureau, which operates the dam.

But that momentum is coming from Washington, not Sacramento.

“The new administration came in and they’re looking to add storage in California,” Bader explains, “and this was the one project that was ready to go, so that’s why it’s got most of the attention right now.”

Wild & Scenic

The project has also caught the attention of California officials, who say it violates the state’s Wild & Scenic Rivers Act, which protects one of the three major rivers that flow into Shasta Reservoir.

“The California Legislature protected the McCloud River from any construction that would expand the reservoir,” says Ron Stork, of the advocacy group Friends of the River. “It’s been illegal to expand this reservoir since 1989.”

Environmentalists say that the $1.3 billion dollars could be better spent on more creative ways to conserve water, such as recycling, stormwater capture, and storing more water in underground aquifers. But President Trump is on the record promising Central Valley farmers more water.

“Any bean-counter would say this is crazy,” says Stork. “But this is a political dam.”

The additional 630, 000 acre-feet of capacity would be like taking Hetch Hetchy Reservoir — the Sierra lake that supplies San Francisco — and dumping it into Shasta … twice.

But nature is not likely to fill that order every year. Stork says the project would likely yield only about 50,000 acre-feet of water on average, annually. That’s a drop in the bucket relative to California’s water budget.