These Hairworms Eat a Cricket Alive and Control Its Mind

The rains in California bring out more than mushrooms and newts. If you’re looking down at the puddles this winter or spring, you might spot a long, brown spaghetti-shaped creature whipping around madly in a figure 8.

It’s a hairworm — also known as a horsehair worm or Gordian worm. Good news: It isn’t interested in infecting or attacking humans. But if you had happened on the puddle a few hours earlier, you might have witnessed a gruesome spectacle — the hairworm wriggling out of a cricket’s body, pushing its way out like the baby monster in the movie “Alien.”

How a hairworm ends up in a puddle, or another water source such as a stream, hot tub or a pet’s water dish, is a complex story. A young hairworm finds its way into a cricket or similar insect like a beetle or grasshopper, and once it has grown into an adult, it takes over its host’s brain to hitch a ride to the water.

Scientists are slowly unraveling the details of the hairworm’s and cricket’s relationship. What they learn could shed light on parasites that impact human health, such as toxoplasma, which is transmitted in the feces of cats and lodges in the human brain. That parasite can cause brain damage in the babies of infected mothers.

“Toxoplasma is one that gets into your brain and changes your behavior. And that’s really hard to study in humans,” said Ben Hanelt, a biologist at the University of New Mexico who researches hairworms. “So we need models to study that, and we know that the horsehair worm system is one where the worm does manipulate the host to do certain things for the worm. And so it’s interesting to sort of look at exactly how this manipulation takes place.”

Researchers have described about 350 species of hairworms around the world. Different ones infect different hosts and have slightly different life cycles. But in general, a hairworm’s journey starts in a river or stream, as one of many eggs in a long, whitish egg string laid by a female hairworm.

The eggs grow into squiggly larvae, which get eaten by other developing insects at the bottom of the river, like mayflies. Once inside a mayfly larva, the hairworm larva burrows into the mayfly’s flesh. Then it curls up, grows a hard shell and waits. But the mayfly is just an intermediate host; the hairworm can’t grow inside it. It can develop only inside a cricket, its final host.

So the hairworm sits tight while the mayfly larva grows into an adult and heads to dry land. Crickets like to eat dead mayflies, and that’s how the hairworm gets inside the cricket, uncurls and starts feeding on fat inside the cricket’s body.

“When they’re infected, the worm takes over and the worm grows, and those crickets are in a developmental hiatus,” said Christina Anaya, who is writing her doctoral dissertation on hairworms and crickets at Oklahoma State University.

Anaya found that over the course of the month it took hairworms to grow inside crickets in the lab, the hairworms absorbed all of the crickets’ lipids, which are the insects’ source of energy. As a result of this deprivation, crickets stop growing and reproducing.

Male crickets infected by hairworms even lose their chirp, said Hanelt, who studied this phenomenon with a team at Texas A&M University-San Antonio. Chirping is the sound male crickets create by rubbing their wings together to keep the competition away and attract a mate. By preventing crickets from chirping, hairworms minimize the amount of energy the crickets need and also protect them both.

“When the male chirps, he draws in predators, possibly,” Hanelt said. “The worm wants to just shut all that down and ensure the survival of the host.”

So even as the hairworm is hurting the cricket by absorbing all its energy stores, it’s also keeping it alive. In fact, Hanelt believes that the hairworm transfers its own immune system to the cricket to keep it healthy.

The hairworm needs to keep the cricket alive to hitch a ride to the water. Crickets usually avoid bodies of water — they’re not great swimmers and become an easy target for birds and fish.

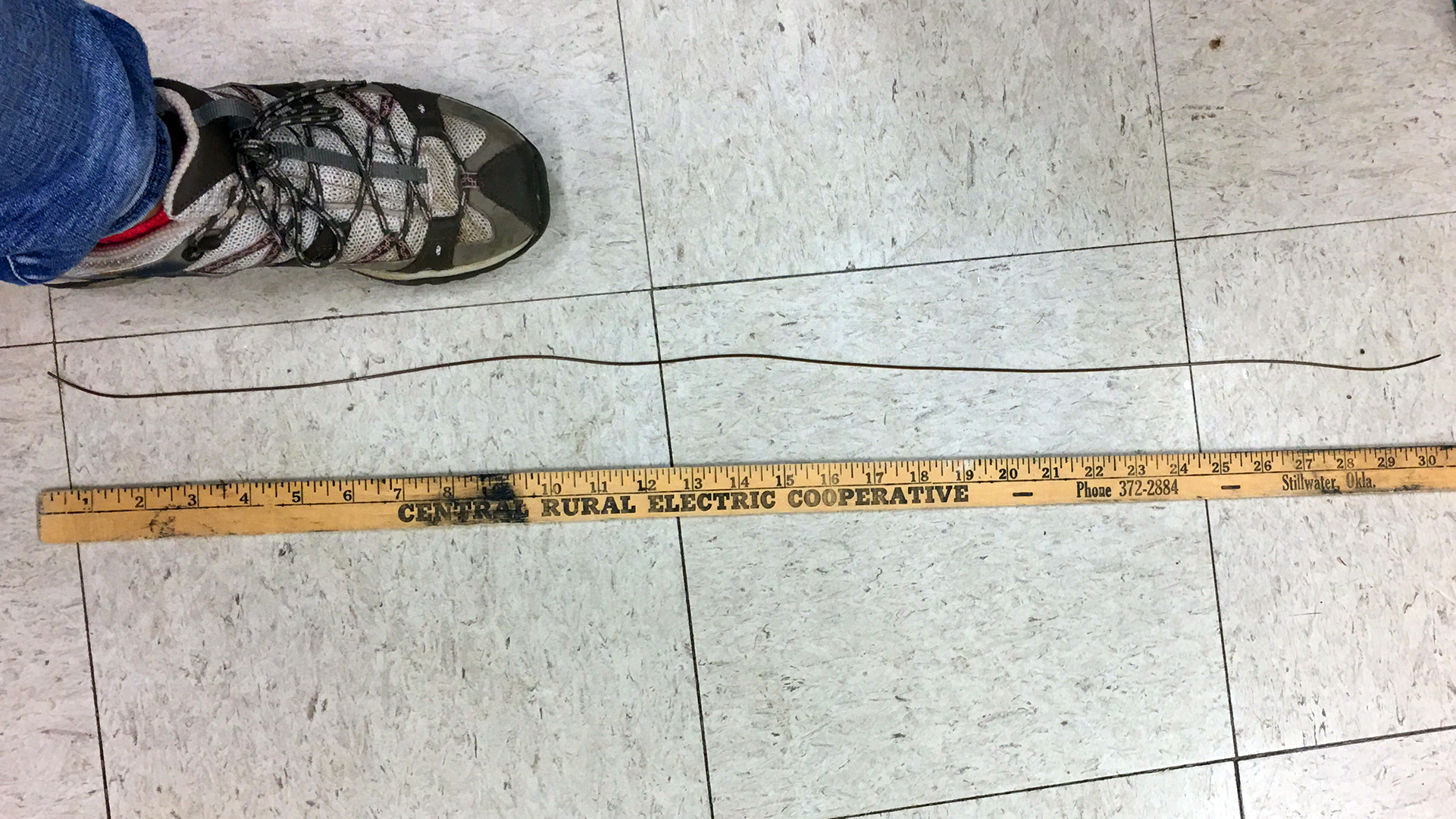

So after the hairworm has reached adulthood — growing from 1 to 2 feet long — it takes over, boosting chemicals in the cricket’s brain that make the cricket walk around mindlessly, until it happens to reach water.

It’s not that the crickets can smell the water, or sense it from far away. Frédéric Thomas, of the IRD research institute in Montpellier, France, watched and performed experiments on crickets infected by hairworms in a forest in the south of France. After two summers, he and his colleagues concluded that infected crickets weren’t somehow detecting water from afar. Instead, the researchers believe that the hairworms made the crickets walk around erratically so that sooner or later they would arrive at a body of water. Once the crickets were close to the water — a thermal pool, in one experiment – then they jumped in. In video recordings, the hairworm bursts out almost immediately from the cricket and, after thrashing around to extract itself, swims away.

Sometimes more than one hairworm is inside. And when several emerge from a single cricket, they don’t waste any time, curling around each other to mate, even before they’re fully outside the cricket. Then they lay egg strings and the cycle continues.

As for the crickets, if they end up in a stream, the current can carry them away and they’ll drown. Researchers believe that some hairworm hosts, like Jerusalem crickets, die when the hairworm emerges, regardless of whether they drown or not. But Anaya, at Oklahoma State University, has done research that shows that, in the lab at least, most crickets actually survive after the hairworm emerges.

Anaya tested female house crickets — the kind that are commonly sold at pet stores and widely used in the lab by hairworm researchers. All but one of the 22 infected female crickets survived after a hairworm, or several hairworms, had grown inside them and emerged.

“Once those worms emerge, then they can start being a cricket again and growing and living a daily life, so to speak,” Anaya said.

Whether the male crickets ever get their chirps back remains an open question.

Amanda Heidt contributed reporting.