Anyone fond of intricate intellectual property disputes (and really, who isn’t?) is going to have their cup runnething over when it comes to the long-running battle between the University of California and Harvard/MIT’s Broad Institute to determine who will get to cash in the most on their seminal CRISPR/Cas 9 discoveries.

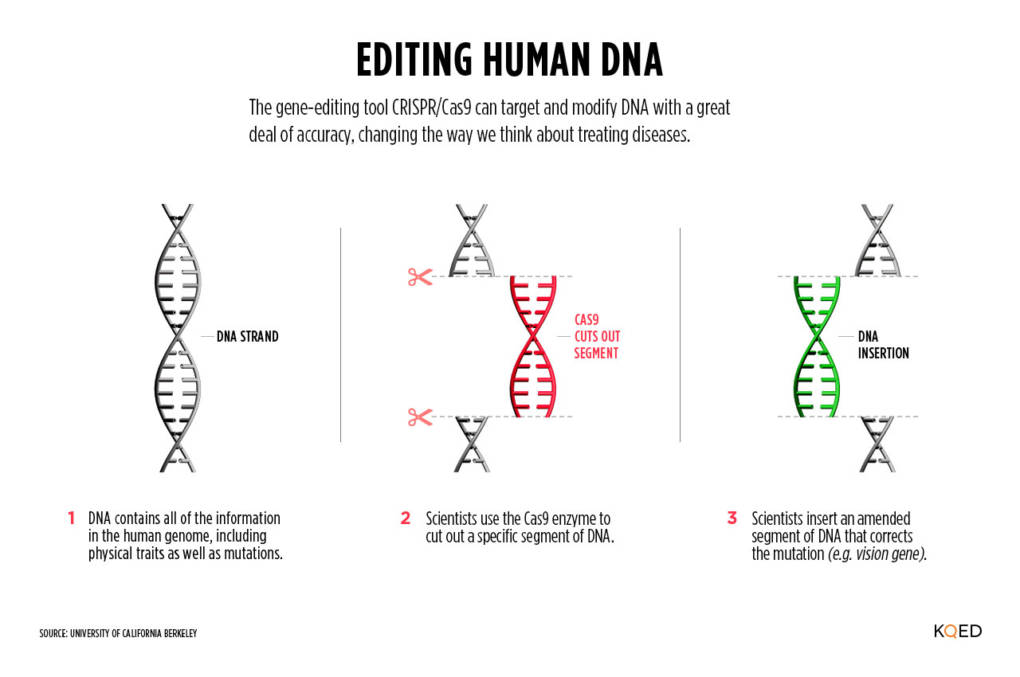

CRISPR/Cas9 is a precise gene-editing technology. Scientists can use it to home in on specific locations within the human genetic code to swap out a problematic section of DNA with a corrected segment. The advance has created enormous excitement over its potential for curing or preventing genetic diseases, and galvanized an ethical debate over human genome editing.

UC and Broad have been slugging it out in administrative hearings and the courts since 2014, when Broad, which had paid for an expedited review, received a key patent while UC still waited for approval on its own filing. UC eventually lost the legal fight, but on Feb. 8, news broke that the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office will finally issue UC’s foundational CRISPR/Cas9 patent. Not everyone expected the decision, and it has created a potentially even bigger muddle over who will get paid for what should the considerable hopes for the technology come to fruition.

To sort out the complexities, KQED spoke with two people following the case, reporter Sharon Begley of the health news website STAT, and Professor Jacob Sherkow, of the Innovation Center for Law and Technology at New York Law School. Some key points …

What’s the history of the dispute between Broad and UC?

In 2012, University of California Berkeley biochemist Jennifer Doudna and colleagues made a seminal discovery about how to use CRISPR/Cas9 for gene editing, performing their experiments on DNA in a test tube. UC subsequently filed with the United States Patent and Trademark Office for a patent on the process.

In 2013, a group led by molecular biologist Feng Zhang at the Broad Institute in Boston also edited genes using CRISPR. This team was able to edit the DNA inside of actual mouse and human cells. Broad filed for a patent on its process, and in 2014 the United States Patent and Trademark Office granted the patents.

At that point, UC claimed the Broad patents “interfered” with the patent for which UC had applied. “That’s called an interference proceeding,” Begley said of the legal maneuver. “Lawyers make gazillions of dollars on it.”

But the tactic didn’t work. In February 2017, the Patent office ruled that Broad’s patents were sufficiently different from the one UC claimed, so no interference had occurred. UC then took Broad to court, and in September 2018, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit affirmed the patent office’s decision to award Broad its patents.

“So at this point, and again, we’re six years later, UC’s (2013) patent application is still sitting there at the Patent and Trademark Office,” said Begley. “And what happened on February 8 is that the patent office finally said, ‘UC, we are going to give you this patent that you applied for on the basic use of CRISPR in all kinds of cells.’ And that should be very good news for UC.”

Jacob Sherkow, a patent law expert who has been following the case closely, wrote in an email that he was surprised at the news that UC is going to be awarded the patent for which it filed in 2013. He thought UC would run into trouble given the filing of an earlier patent from a Lithuanian researcher named Virginijus Šikšnys, who won the prestigious Kavli Prize last year for “seminal” CRISPR advances. Science magazine called Šikšnys an “overshadowed” researcher in the field.

“Surprisingly — and I wasn’t the only one surprised — the patent office assigned the patent to a new examiner, who simply allowed the patent with only minimal comment,” Sherkow said.

How much are these patents worth?

A lot of companies are trying to produce human therapies using CRISPR. If they succeed, “that market almost certainly will be worth tens of billions of dollars per year,” said Begley. But the holder of the patent that enables these advances won’t get a huge slice. Despite early reports that the patents might be worth billions of dollars, she said the figure will “almost certainly be in the millions of dollars.”

Sherkow’s back-of-the-envelope calculation puts that figure at “easily tens of millions” per year, or $100 million over the life of the patent. Developments over the last several years, he says, have diminished the stakes.

“When the case was first filed, it was unclear whether enzymes other than Cas9 would have the same efficacy. Now, we’ve got a riot: Cas12, CasX, CasY, etc. ”

Begley said the scientists she’s spoken to “have sort of been rooting for UC because it’s a public institution,” whereas Harvard and MIT are private universities. With the funding difficulties UC has had over the years, “if a significant revenue stream can come to UC as a result of [CRISPR patents], there’s just a lot of people who are hoping that happens,” Begley said.

Is the dispute over?

The Broad Institute could challenge UC’s patents in a procedure called a post-grant review, said Sherkow. He said Broad has nine months from the date the UC patent is issued to do that.

“Alternatively, there may be an opportunity to bring a lawsuit in federal court challenging the UC patent,” he said.

For now, it appears UC and Broad may both need to be compensated for any applications using CRISPR in humans. Begley said we’re “years away” from knowing the final outcome of the dispute. “Not until there’s an actual commercialized therapy.”

And there could be one more complication down the road: Another expert in intellectual property and innovation, Stanford Law Professor Lisa Larrimore Ouellette, told Begley that UC’s patent could be vulnerable to challenges based on something called the “enablement clause,” which requires that patents allow for anyone to follow a series of steps to carry out the invention. Sherkow agreed UC’s patent may fall short in this regard.