Beginning July 1, lead ammunition is banned for hunting wildlife anywhere in California.

It’s the final phasing in of a law California passed in 2013. Governor Jerry Brown signed it in large part to protect the threatened California condor.

The recovery of condors is being held back primarily by the presence of lead in the bodies and gut piles of the animals they scavenge upon, research indicates. Myra Finkelstein is a wildlife toxicologist at UC Santa Cruz, and one of the researchers who testified in hearings for the bill, and whose work helped lay the case for a lead ammunition ban. She spoke with KQED’s Brian Watt about how lead affects animals in the environment.

The following excerpts have been edited for length and clarity.

Can you give us an overview of what lead does to animals?

Lead is a equal opportunity killer. It is toxic to many vertebrate species, and that includes humans. It can harm your immune system, reproductive system, nervous system, renal system, many systems. It’s a very well known toxic compound.

In fact, the Centers for Disease Control has said there is no safe level of lead exposure for a young child. So another way of putting that: that any exposure to a young child has been shown to result in long-term neurological impairment.

What has lead meant for the California condor?

Lead is the number one mortality factor for free-flying juvenile and adult California condors, and work that we have done has shown that lead poisoning is preventing their recovery. So it is the major threat that’s impeding their ability to recover in the wild.

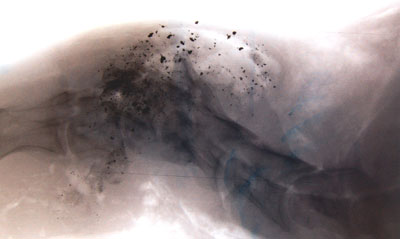

Lead ammunition, it fragments. So people can look up online, you can see a radiograph and it’s all these tiny, tiny little pieces throughout the carcass. When the condor is eating its meal, we think they accidentally then ingest a little bit of these lead fragments. Even fragments as small as a couple of grains of sand have enough lead to potentially kill a condor. It doesn’t take very much.

Your research was important for showing that lead found in scavenging birds, like condors, is actually coming from ammunition, instead of from the environment, such as paint chips or lead pipes. How did you do this?

Lead has different isotopes, which creates a lead signature or a lead profile. It is almost like a fingerprint, but not quite as unique. This is how we identify sources of lead poisoning to children. We’ve been doing this, as a society, for decades. For wildlife, it’s the same thing. Where you can look at the lead signature in ammunition and look at the lead signature in a poisoned condor, and see whether or not they are similar, to illustrate: was the lead ammunition the source of lead poisoning to the condor? We did that for California condors and showed that lead ammunition was the principal source of lead poisoning for California condors.

Are lead ammo bans working? How long will it take for lead not to be a problem for sensitive species?

So far we have not been able to detect a change in lead poisoning rates in California condors, but part of that problem is that the rates in condors are highly variable, and that one contaminated carcass out there can poison a lot of condors at once. We’ve done some models and we’ve shown that even if 1 percent of the carcasses on the landscape contain lead, each condor can still have a 30 percent to 50 percent chance of encountering a carcass with lead and potentially being poisoned. It’s going to take a lot of time for us to be able to statistically assess if there’s been a change in lead poisoning rates.

But I do think that a person switching to non-lead ammunition will be an immediate benefit to any scavenging species that might come across that person’s gut pile. As well as for a hunter and their family, as lead is highly toxic.