Extreme heat grounds planes in Arizona. Last year in Australia, the government blamed it for melting tires on a road. And during a particularly brutal July in 2006, heat killed at least 163 Californians, with state epidemiologists estimating that it contributed to hundreds more deaths.

This Will Be a Sweltering Century in California and the Nation

If emissions aren’t seriously curbed — that is, even if the climate continues to warm with some abatement — researchers at the Union of Concerned Scientists say millions more people in California alone can expect at least a month of extreme heat days each year, those days bringing with them more health risks and rippling environmental impacts.

“Even in the next few decades we’ll see major increases in the frequency of really hot days,” says Kristina Dahl, a researcher with the Union of Concerned Scientists, who authored the study. “These results are really terrifying to me.”

Global climate models project how the planet will warm under various scenarios, anticipating a range of atmospheric conditions. The study’s authors ran climate models with two different emissions scenarios: one, where emissions begin to be curbed by mid-century; and a second, where no policies achieve significant reductions in emissions. Using daily high temperatures, the researchers calculated what’s known as heat indexes for cities and counties around the country; the heat index is what the temperature “feels like” when humidity is taken into account.

Along a national “sunbelt,” inland cities, including in California’s Central Valley, could count dramatic increases in days with a heat index above 105 degrees. Until recently, Fresno averaged three such days a year, but the study found by late century, Fresno could have 58 days that feel like 105 degrees, in the absence of emissions limits. Even if governments rapidly move toward arresting global warming at a threshold of 2 degrees Celsius, parts of the Central Valley could still experience more than two-and-a-half weeks of heat that severe each year.

Where high heat is already common, as in Southern California, the study projects it will continue to grow. Los Angeles has experienced a heat index of 90 for twenty days a year, on average; even with some emissions curbed, the study projects that number will triple toward the end of the century.

Indio, a Sonoran Desert town in San Bernardino County, historically has racked up more than 100 high heat days a year, but it’s been rare that the heat index is so high as to be “off the charts.” Without action to curb emissions, the study’s authors say Indio can expect, on average, 37 days a year of excessive and dangerous heat.

Significantly, modeling suggests that the most dramatic transformations in the state are likely to come where the climate has been temperate — along the coast and in Northern California. Within a half century, the Sonoma County town of Petaluma could have 11 times as many days where the heat feels like 90 degrees. Santa Barbara County could have 27 times the number of days where that happens.

No one heat index or temperature definitely protects against health risks, and no one threshold triggers public response to heat. According to the National Weather Service, heat cramps, sun stroke, and heat exhaustion are possible at a heat index of 90 for some groups; in California, state labor regulations offer outdoor workers additional protections at that point. At a heat index of 105, according to federal authorities, even healthy adults are at risk.

The study may well underestimate some contributions to rising heat, especially in cities. In the built environment, concrete, asphalt and glass warm cities; so does energy consumption, including air conditioners that release heat to the atmosphere; so do greenhouse gases, like those released from cars and power plants. The resulting urban heat island isn’t accounted for in the new study, according to Dahl.

“That makes some of the results we have for cities conservative,” she says, “because, realistically, they’ll be experiencing even hotter temperatures earlier than we’re projecting.”

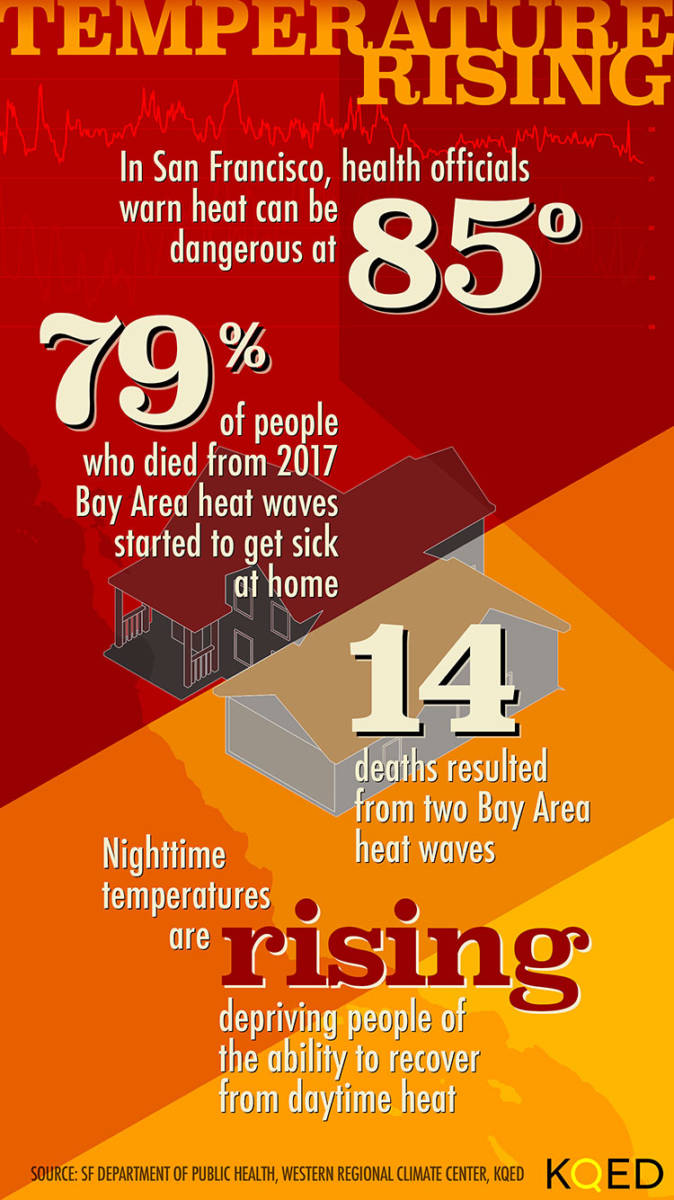

And the projections don’t account at all for some other climate-driven temperature shifts. In temperate northern California, nighttime lows have risen, making it harder for people’s bodies to recover when they become overheated. In 2017, during a Labor Day heat wave in San Francisco, it was still 80 degrees near midnight; that weekend, the city’s coroner’s office counted six deaths attributable to heat.

While Dahl says the new study focuses solely on high heat index days, “we do know that if people don’t have the opportunity to cool down at night, their bodies just carry that potential heat stress over from one day to the next, and that can build up over time.”

Some Bay Area counties trigger warnings well below a heat index of 90 degrees. The city of San Francisco considers it an extreme heat day when temperatures hit 85; based on Cal-Adapt projections, by late century city officials are planning for that to happen 15 days a year. Last month, San Francisco’s departments of public health and emergency management updated the city’s emergency plan, including directions for respite centers.

Some Bay Area counties trigger warnings well below a heat index of 90 degrees. The city of San Francisco considers it an extreme heat day when temperatures hit 85; based on Cal-Adapt projections, by late century city officials are planning for that to happen 15 days a year. Last month, San Francisco’s departments of public health and emergency management updated the city’s emergency plan, including directions for respite centers.

During a heat wave last month in San Francisco, two sites in Bayview and Hunters’ Point, Mother Brown’s Kitchen and the Adult Day Senior Center, provided cooling resources to their clients. The San Francisco Foundation has funded that work with a grant to the Resilient Bayview initiative, a program of the city’s Neighborhood Empowerment Network. The network also sponsors block-by-block potlucks known as Neighborfests; the idea is that through planning a party, neighbors can develop skills in community resilience and disaster response. This year, San Francisco’s Neighborfest idea is expanding in the East Bay and in Santa Rosa.

But experts say planning for diffuse and spotty heat waves in the greater Bay Area is challenging when there’s no historical practice or a response infrastructure.

“I’ve had the impetus to take my kids to the library, thinking, ‘Well, of course the library will be cool,’ but not all of the libraries here are air-conditioned,” says UCS’s Dahl, a San Francisco resident. “So we don’t have places to escape the heat when our homes aren’t air-conditioned here in the Bay Area.”

Risks related to heat, such as wildfires and air pollution, aren’t analyzed in the study. And local public officials are still taking the full measure of heat’s impacts. In San Mateo County, officials are using a CalTrans planning grant to study climate hazards, map heat islands where the tree canopy is low and more vulnerable people live, and communicate risk to the public.

Jasneet Sharma, an acting program manager for sustainability in San Mateo County, says the county is considering wider impacts. For example, sustained high temperatures threaten public transit systems by warping tracks.

“An inability to cool homes would mean not just discomfort but unsafe conditions for seniors, farmworkers on the coastside and vulnerable community members,” Sharma says. “We know for certain we’re going to be impacted by rising heat. The full story goes beyond just the temperatures.”