For astronomers, collectors and lunar enthusiasts in general, moon rocks, it seems, still rock.

Fifty years ago this month, Apollo 11 astronauts bagged and brought home the first specimens from the lunar surface: rocks, soil, and even dust.

For astronomers, collectors and lunar enthusiasts in general, moon rocks, it seems, still rock.

Fifty years ago this month, Apollo 11 astronauts bagged and brought home the first specimens from the lunar surface: rocks, soil, and even dust.

This week at Christie’s auction house in New York, buyers are bidding on lunar meteorites — small chunks of the moon that landed on Earth without the aid of NASA. Some are likely to sell for hundreds of thousands of dollars. In a related auction of moon memorabilia, a Christie’s auctioneer was apparently so impressed that a strap had picked up some lunar dust on an Apollo mission, that she declined to sell it, passing on the top bid of $38,000.

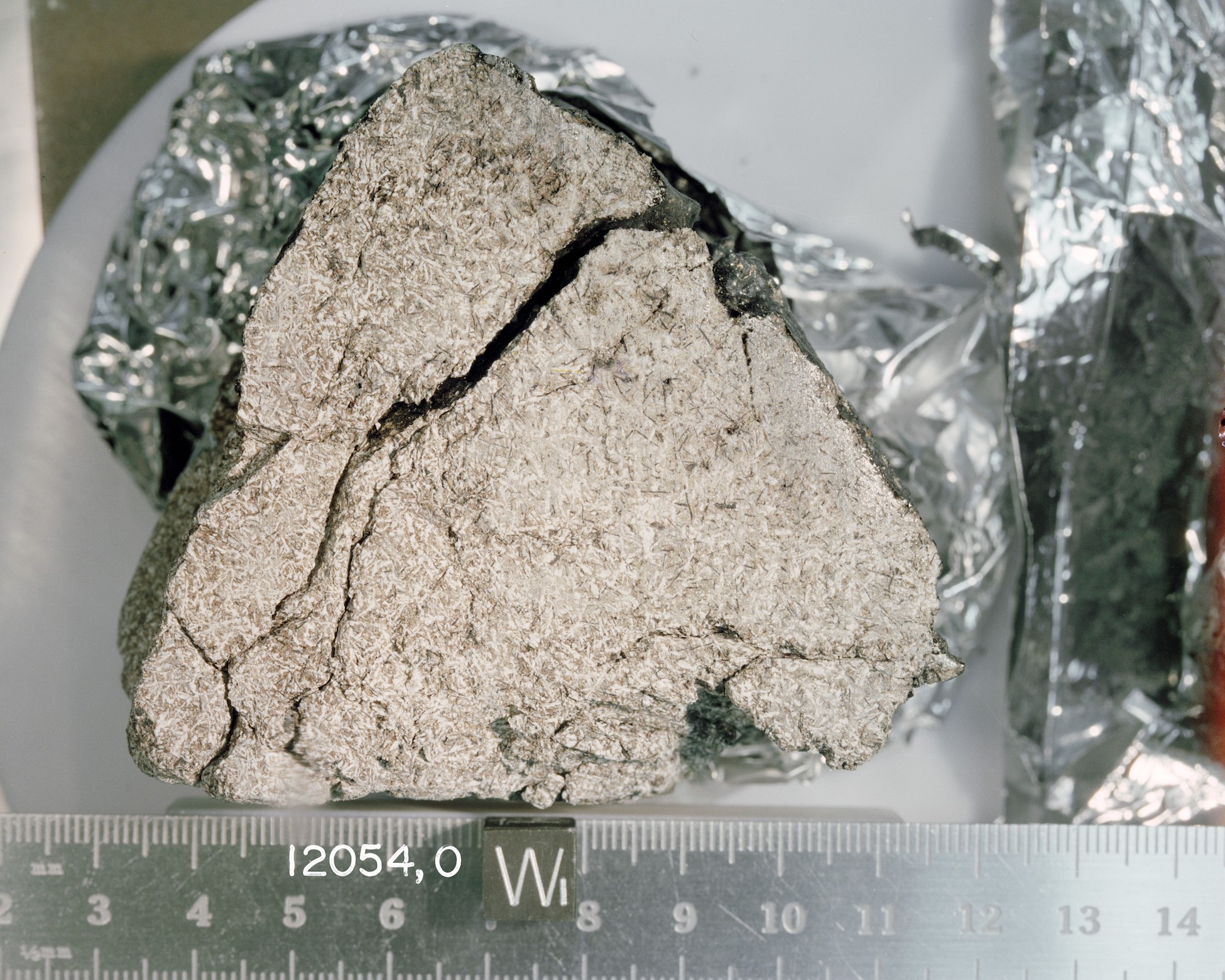

Scientists’ fascination is undiminished as well. Over the years, curators at the Johnson Space Center in Houston have provided more than 50,000 samples (many of them tiny, fragmentary bits) to scientists for study.

Locked Up for Posterity

The six Apollo missions that made it to the moon brought back about 845 pounds of rocks, soil, and core samples, but much of it has been locked up in a NASA vault ever since their return, waiting for better analysis techniques to evolve. This fall, NASA will open some of those up for the first time.

“I’m definitely very excited about it,” says Richard Walroth, a scientist on one of nine teams that will get first crack at the newly unveiled moon matter. “It’s just almost surreal in a way, the thought that I get to work on samples that were brought back from the moon.”

He’ll be looking at the samples’ chemical properties, as part of a team at NASA Ames Research Center in Mountain View. His work could shed more light on the origins of the moon and Earth, since both bodies likely share a common geologic history.

“From a scientific perspective,” he explains, “we want to know how old the Earth is, we want to know how long ago did life arise on the Earth.

So far, the story line that scientists have advanced is that the moon is essentially shrapnel — a clump of debris flung from when a space object the size of Mars collided with Earth in its early stages.

“That impact would have completely sterilized the Earth,” says Walroth. “So at a minimum, it would provide an absolute oldest age for life to have arisen on the Earth, because there’s no way that life would have survived that dramatic of an impact.”

Orange is the New Gray

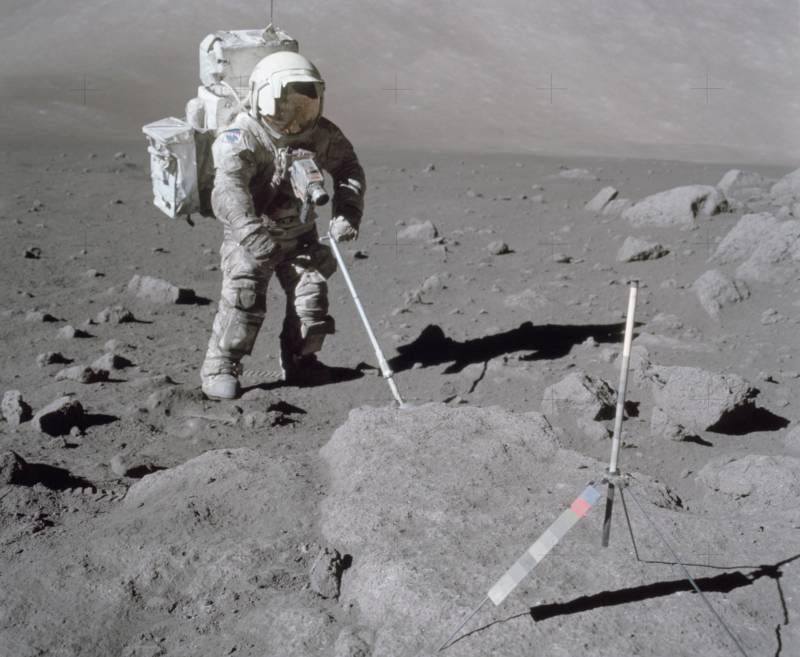

When Apollo 17 left the pad in December of 1972, it had something new on board: a geologist.

Harrison “Jack” Schmitt would become the first (and only) astronaut-scientist to walk on the moon. And he was barely able to contain his excitement.

“Oh my golly! Unbelievable,” he blurted out over the radio during his moonwalk.”I never thought I’d do geology this way.”

During his outing, he narrated various features of the topography and rocks he encountered until, there amid the grey lunar landscape: not green cheese, but one of the more startling discoveries from Apollo.

“Hey!,” Schmitt famously shouted to his fellow moonwalker, Gene Cernan. “There is orange soil! It is all over — orange!”

That “orange soil” turned out to be tiny beads of volcanic glass, from a volcanic eruption maybe 4 billion years ago.

“Those samples have turned out to be some of the most important samples that we collected,” recalls Francis McCubbin, an astromaterials curator and one the keepers of NASA’s lunar sample collection. He says those glass beads helped unlock secrets into our collective past, and affirmed the foresight that someone at NASA had to wait for analytical tools to advance.

“Especially with more recent studies, within the last 10 years,” says McCubbin, “they’ve been one of the key samples for understanding the history of water on the moon and the fact that the moon had any water at all.”

That’s a fairly recent revelation…and lunar samples from Apollo helped provide some of the first clues.

The Crown Jewels

“Lunar samples are more valuable than the crown jewels,” declares Kimberly Ennico Smith, a NASA astrophysicist who has been studying the moon from Earth for decades. As payload scientist on a milestone lunar probe in 2008, she helped explode the myth that the moon is bone-dry.

“When we look at the moon,” she says, “the moon becomes an opportunity to learn a lot more about our early Earth, because the early stages of the solar system, the early years of the solar system are recorded on the moon.”

Confirmation of water on the moon could also be a key to making the moon a way station for missions to more distant targets, such as Mars.

“One of the big challenges in launching anything into space is getting above the earth’s gravity well,” Ennico Smith explains. “If you’re able to build your infrastructure in space or from the surface of, say, the moon, which is nearby, a few days journey, and which has less gravity than the earth, and you’re able to make things in space that can sustain that infrastructure, it’s all about that type of exploration.”

Some of the 2200 samples in NASA’s collection will stay locked up awaiting further advances in technology. McCubbin says that 80% of the mass of the Apollo collection remains stored in a pristine condition, “so the collection will be able to sustain intense scientific study for generations to come.” Still, the prospect of gathering fresh samples, either robotically or by hand, has scientists salivating.

Jack Schmitt threw down the gauntlet to keep collecting lunar samples back in 1972.

“I think the next generation ought to accept this as a challenge,” he told Cernan while Mission Control listened in. “Let’s see ‘em leave footsteps like these some day.”

“The science is not over,” says Ennico Smith. “It’s far from over. There’s this exciting opportunity today looking at samples that were taken 45, 50 years ago, and then the future samples that will help us answer open questions.”

Those fresh footprints that Schmitt envisioned might appear sooner rather than later. NASA’s under heavy pressure to get boots back on the moon by 2024. And Ennico Smith isn’t content with more analysis of the lunar samples we already have.

“This new resurgence in actually getting more samples from the moon is going to once again change the way we think about the moon,” she says, “and how we use the moon, and also understand our place in the solar system.”

To learn more about how we use your information, please read our privacy policy.