Fifty years ago, on July 24, 1969, the U.S.S. Hornet was 900 miles southwest of Hawaii, ready to recover the Apollo 11 astronauts upon their return to Earth.

Today, the aircraft carrier is docked in Alameda and is open to the public as a museum. It’s a time capsule back to the day when our most daring explorers took their first steps on Earth after visiting the Moon.

The Hornet’s role in space history is the big reason it didn’t get scrapped after being decommissioned in 1970. Though the Apollo 11 assignment was kind of a fluke.

“The world generally thought the Apollo 10 recovery ship, the Princeton, would [also] do Apollo 11,” says Bob Fish, author of Hornet Plus Three. He’s a former Marine, the Apollo curator for the USS Hornet Museum, and the world expert on the recovery of Apollo 11.

Right Place, Right Time

In early June 1969, Fish says, the Hornet was “the only aircraft carrier that wasn’t either going to Vietnam or being replenished or repaired was the Hornet, which had just come back from Vietnam.”

The crew had finished a six-month tour. Some hadn’t even left the ship yet when the new assignment came in.

“And then it’s like, ‘All hands back on deck, we got to go recover these guys.’ If you really sit down with a crewman and you give him a beer he’ll say, ‘Yeah I wasn’t really happy about that.'”

But the crew were galvanized by the realization that their ship would soon be the center of the nation’s attention.

“All of a sudden the morale just changed completely,” says Fish. “[They thought:] ‘Oh my God. They actually are going to land on the moon and the President’s going to be here? Oh yeah!’ The mood flipped.”

One of the members of the recovery team was John McLaughlin. He was a swimmer on the Underwater Demolition Team, sometimes called the “frogmen” (precursors to the Navy SEALs). If you’re wondering how someone comes to specialize in plucking newly-landed astronauts out of the ocean …

“Somebody just said, you’re going to do it. It was a job, but we took it very seriously and it was fun,” says McLaughlin, who also worked recovery on Apollo 8.

Precision Practice

Astronaut recovery is a high-stakes affair, with an intricate choreography. Everyone wanted to make sure Apollo 11 had a picture-perfect finish.

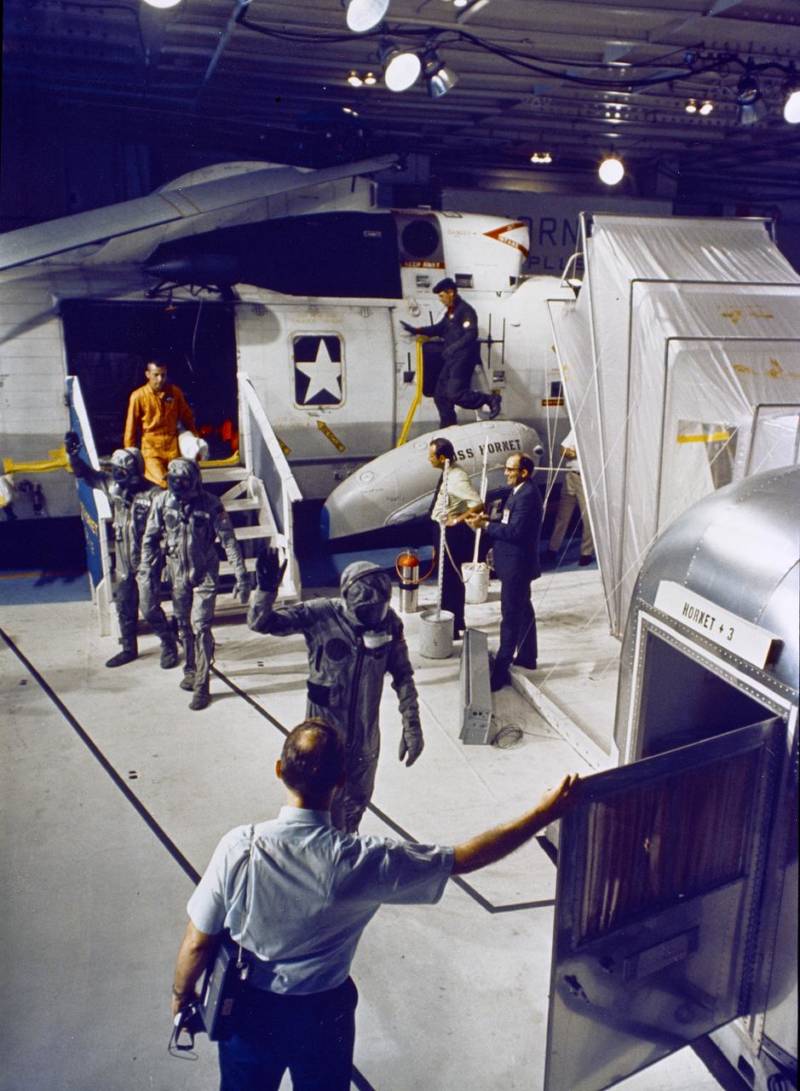

They practiced again, and again, and again — 26 times over a 10-day period. They had to jump out of helicopters, swim to a mock-up Command Module known as a “boilerplate,” and attach a sea anchor. Then, a different swimmer would affix a flotation collar that would surround the module, which the astronauts would step out on to.

“Then there was a separate swimmer on Apollo 11 that brought the contamination suits and kind of washed them down to make sure no moon germs got around,” says McLaughlin. (The three long-distance travelers had been breathing moondust ever since Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin got back to the Lunar Module.)

After getting sprayed and scrubbed with bleach, the astronauts would climb onto a raft, and from there into a net that functioned like a chair (known as a Billy Pugh net) to be hoisted into a helicopter hovering overhead.

Simulations didn’t always go as planned … they could be downright dangerous.

“We practiced during the day and [at] night, so one night we jumped in and we jumped into probably 30 or 50 sharks. I mean, the water was just kind of boiling,” McLaughlin remembers. “We were 25 to 50 yards from the Command Module, the boilerplate — and nothing but sharks between us. There was no place to go in the middle of the ocean. So we just swam like hell and counted our lucky stars.”

But the morning of the real recovery was shark-free. McLaughlin and the rest of the recovery team started off for the targeted splashdown site about an hour before sunrise.

“I remember we saw the fireball. It was the Command Module re-entering,” he says. “And that was very exciting. We thought we were ready but you see that, boy, that got the heartbeat going a little faster.”

The swimmers’ recovery went off without a hitch. A helicopter crew hoisted them up. Then, a three minute flight back to the Hornet to be welcomed back as heroes.

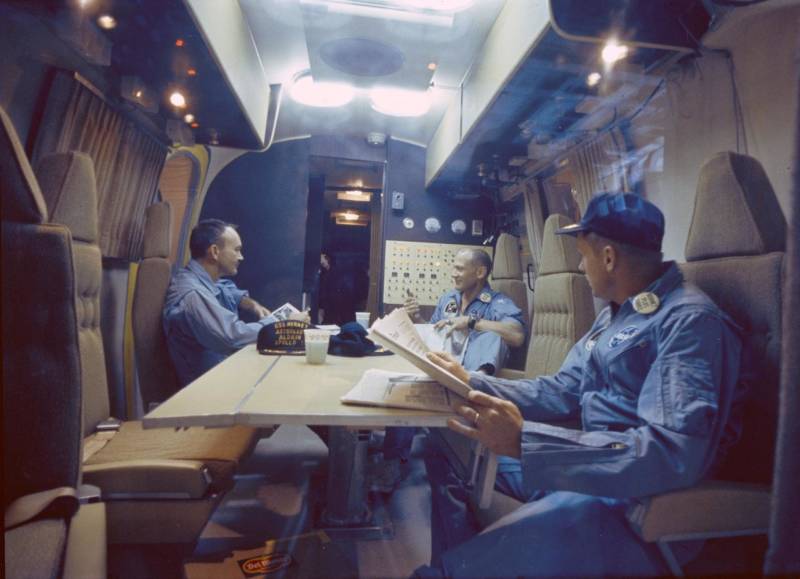

The astronauts walked from the recovery helicopter into an Airstream trailer outfitted as a mobile quarantine facility. They took showers, changed into NASA jumpsuits and then, with a window separating them, were welcomed by President Nixon.

“I want you to know that I think I’m the luckiest man in the world,” said the President, “because I have the privilege of speaking for so many in welcoming you back to Earth.”

Then the ship set sail for Pearl Harbor. The astronauts would go on to spend three more days in the Airstream and 21 days total in quarantine. Fish has spoken extensively with Neil Armstrong, who told him they appreciated the time spent apart from the hubbub.

“It gave them some breathing space because they’d just been through the most incredible thing. I mean, they spent a lot of time crammed together in this little tiny aluminum can. The next thing you know, they’re down on the moon, walking around on the moon. When they come back, they needed to sort their thoughts out.”

And compared to their spacecraft, the Airstream trailer felt like a mansion.

Today, the Hornet is maintained just as it was in 1969, complete with war planes and space memorabilia. The Apollo 11 exhibit boasts an Apollo Command Module (used in earlier testing), plus a “Sea King” recovery helicopter and a Mobile Quarantine Unit you can visit. It’s is one of only three in the world and the only one you can enter.

“That’s what’s so cool about the Hornet,” says Fish. “You actually get a visceral feeling for it. It’s not just a video on TV.”

Fish hopes the museum can help rekindle something he thinks we’ve lost as a society: big, crazy dreams.