California is pushing back on the federal government’s proposal to delist wolves from the Endangered Species Act in the lower 48 states. This step would remove wolves’ federal protections, transferring decisions about wolf management to individual states and tribes.

The proposal, announced in March, frames the wolves’ current status as “one of the greatest comebacks in conservation history.” But environmentalists and now the California Fish and Game Commission have argued that, to make a full recovery, wolves still need Endangered Species Act protections.

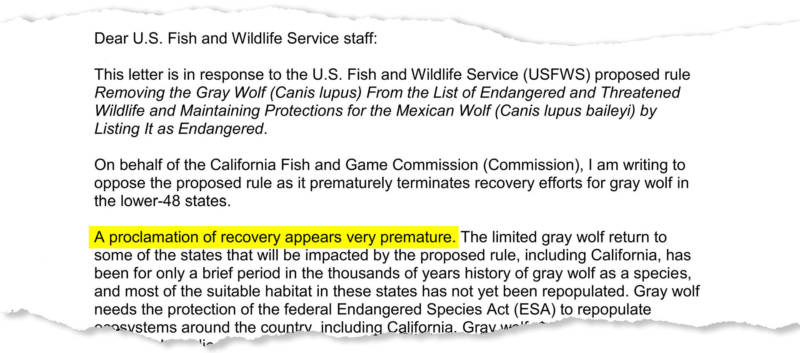

On July 15, the Commission sent a letter to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services, strongly opposing the proposed delisting. The letter, signed by president Eric Sklar, states the ruling would end recovery efforts prematurely.

“The limited gray wolf return to some of the states that will be impacted by the proposed rule, including California, has been for only a brief period in the thousands of years history of gray wolf as a species,” states Sklar, “and most of the suitable habitat in these states has not yet been repopulated.”

Just this week, California also announced its intent to file a lawsuit against the Trump administration’s overhaul of the Endangered Species Act. If the changes are implemented, federal agencies would be able to publicly share the economic impact of protecting endangered species. Threatened species, considered by biologists on their way to being critically endangered, would not receive the same protections as endangered species, as they do currently. The review process for actions taken by agencies affecting listed species would simplify. It is unclear how wolves would be affected by these modifications.

Where Wolves Should Roam

Though California wolves would retain their listing in the state’s Endangered Species Act no matter the ruling, the Commission’s stance against delisting is not purely symbolic. The ruling would likely affect the state’s wolf population by restricting the numbers of wolves that enter from other states. After the last wolf in California was shot in 1924, wolves only started reappearing in the state in 2011, when one wandered over the Oregon border. Biologists say that California’s future wolf population will depend on expanding from other states.

“It’s good to see West Coast states that have an interest in wolf recovery speaking out about … the proposal that would undermine wolf recovery in their states,” said Brett Hartl, the government affairs director at the Center for Biological Diversity. “California is a good example of why their proposal doesn’t make sense, because wolves are definitely not recovered in California.”