People who donate their bodies to science might never have dreamed what information lies deep within their brains.

Even when that information has to do with sleep.

Scientists used to believe that people who napped a lot were at risk for developing Alzheimer’s disease. But Lea Grinberg with the UCSF Memory and Aging Center started to wonder if “risk” was too light a term — what if, instead, napping indicated an early stage of Alzheimer’s?

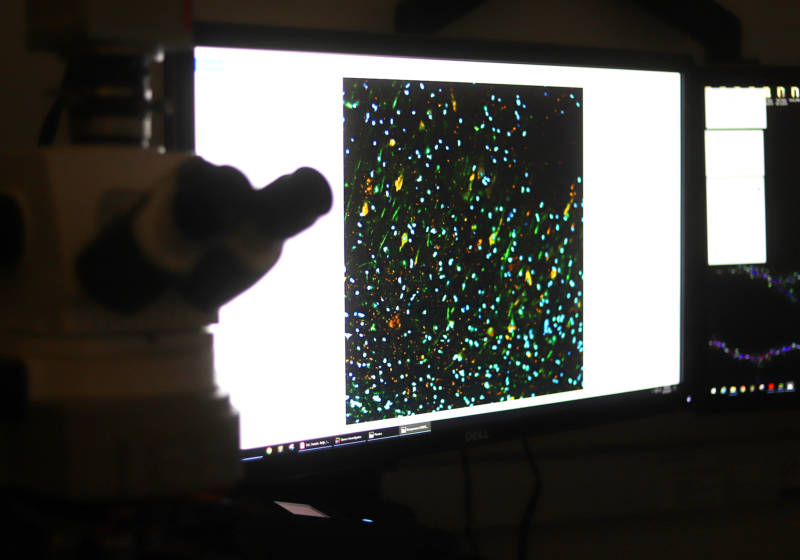

About a decade ago, Grinberg — a neuropathologist and associate professor — was working with her team to map a protein called tau in donated brains. Some of their data, published last week, revealed drastic differences between healthy brains and those from Alzheimer’s patients in the parts of the brain responsible for wakefulness.

Wakefulness centers in the brain showed the buildup of tau — a protein that clogs neurons, Grinberg says, and lets debris accumulate. Gradually, these clogged neurons die. Some areas of the diseased brains had lost as much as 75% of their neurons. That may have led to the excessive napping scientists had observed before. Although the team only studied brains from 13 Alzheimer’s patients and 7 healthy individuals, Grinberg says that the degeneration caused by Alzheimer’s was so profound they were sure of its significance.

“We are kind of changing our understanding of what Alzheimer’s disease is,” she says. “It’s not only a memory problem, but it’s a problem in the brain that causes many other symptoms.”

Although these symptoms aren’t as severe as complete loss of memory or motor functions, Grinberg says they can still hold real consequences for a person’s quality of life. “Because if you don’t sleep well every day and if you… are not in the mood to do things like you were before, it’s very disappointing, right? My grandparents were like this.”

Grinberg says it’s important to know whether napping could be an early sign of Alzheimer’s, for treating symptoms and developing drugs that could slow the progression of the disease. Although there are no prescription drugs available to treat tau buildup, she says, a few are in clinical trials.

A public health professor and neuroscientist at UC Berkeley says the new information offers hope to researchers. William Jagust, who has studied Alzheimer’s for over 30 years, says the results could help select patients for clinical trials of new drugs that require early treatment. “It’s also just very important for understanding the evolution of Alzheimer’s disease with the hope that we eventually will have a drug,” he adds.

It’ll be awhile before doctors can diagnose anyone with Alzheimer’s based on how often they doze off. “There’s no practical application of this to clinical medicine as of today,” Jagust says, “but I think it’s on the cutting edge of the very, very important questions.”