With batteries, California can increase the state’s ability to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by storing energy generated by intermittent renewable resources. The sun doesn’t shine at night, for example, but batteries can absorb excess solar energy and send it back to the grid whenever needed.

“Batteries are a fundamentally different kind of asset than what we have historically placed on the grid,” said Jeremy Twitchell, an energy research analyst with the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. “They are much more flexible and can provide a much wider range of services than what we traditionally have.”

In some instances, batteries can offset the need to build transmission lines and power plants to meet peak demand, and can provide clean backup energy when the grid goes down. Solar power by itself can’t keep the lights on unless it is coupled with some kind of storage.

As climate change bakes the state’s forests and neighborhoods continue to spread into them, batteries can stand in for generators and boost resilience.

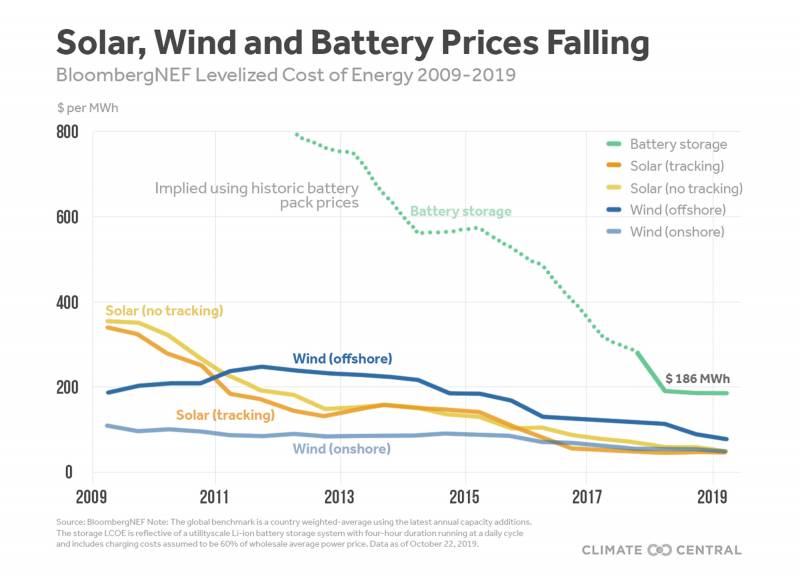

A little more than a decade ago, batteries were inefficient and impractical at grid scale. The cost was too high to store power in large amounts.

California has launched commercially viable projects – a lot of them – because of recent advancements in technology and manufacturing. The state has 262 megawatts of grid-scale storage installed, reports Climate Central, more than any other state.

That’s enough power for nearly 50,000 homes, with much more in the pipeline.

Back in 2013, state lawmakers and regulators mandated the state’s largest investor-owned utilities – PG&E, Southern California Edison and San Diego Gas & Electric – to procure 1,325 megawatts of battery storage by 2020. They are on track to shatter that goal.

The CPUC has approved more than 1,600 megawatts worth of battery storage projects.

Last year, PG&E won the go-ahead for a mega-project in the South Bay that includes a 300-megawatt Vistra Energy project and a 182-megawatt Tesla system, two of the largest battery systems in the world. “These are really breakthrough projects,” said Paul Doherty, a spokesman for PG&E.

Approval is great, but the state’s utilities must keep pushing until these projects are operational, said Alex Morris, vice president of policy with California Energy Storage Alliance.

“The peak for the grid is around 50,000 megawatts,” Morris says. “I don’t want to take away from the hard work, but it is really just the first step. Only a tiny amount of new storage is up and running on the grid.”

Batteries are still more expensive than other energy sources – especially cheap and abundant natural gas – and regulators impose other challenges.

‘Batteries Can Do That, Too’

When temperatures rise during a heat wave, all at once people flip on their air conditioning units to cool down and the demand for power spikes.

That’s when utilities turn to natural gas turbines that spool up and ramp down quickly. But the power comes with a price as the plants belch planet warming gases into the atmosphere.

Gas peaker plants respond to sudden increases in demand by generating power fast, but “batteries can do that, too,” said Chuck Kutscher, a senior research associate with University of Colorado-Boulder.

“For states that are really interested in achieving carbon emissions reductions, they’re looking at batteries to replace gas peakers,” he said.

As the price of batteries continues to fall, California is starting to make this move. East Bay Community Energy, for example, recently signed a contract to replace a gas peaker with a standalone storage facility. But that’s not always possible.

“Natural gas is so cheap right now in the U.S., it makes it hard to compete even though the battery costs are coming down,” said Eric Larson, a senior scientist with Climate Central. “It takes a special situation to make the economics work for replacing peakers. But there are cases where it works.”

This month, energy regulators voted begrudgingly and unanimously to extend the life of four natural gas power plants around Los Angeles based on what they saw as a need for new generation by next summer to prevent outages and price spikes.

CPUC’s new president Marybel Batjer described the decision as “perhaps the most difficult” she’s made since joining the commission. Commissioner Martha Guzman Aceves vowed to “never support another extension,” the San Diego Union-Tribune reported.