We understand how the star at the center of our solar system nourishes life on Earth. But it also burns, fizzes and spews in ways that are bewildering.

It is a long-standing mystery why the sun’s crown, or corona, sizzles at millions of degrees, while the surface beneath is comparatively cool, simmering at only a few thousand. And, curiously, the “solar wind” of particles and magnetic fields blowing off the sun, which fills the entire solar system, accelerates as it increases in distance from it. To investigate, NASA sent a spacecraft straight to the source: the sun itself.

This week at a meeting of the American Geophysical Union in San Francisco, solar researchers presented new findings from the Parker Solar Probe, elaborating upon the initial data release last week.

Scientists are hopeful a better understanding of the sun will improve predictions of solar storms, rowdy ejections of fiery plasma from the sun, which can knock out electrical grids, take out satellites and harm the health of astronauts.

Now that the Parker Solar Probe has made three close passes to the sun, flying closer than any former spacecraft, astronomers are getting an unprecedented view.

“Because we’ve flown through with in situ measurements, we can really understand some of the detail that we’ve only had hints at before,” said NASA astrophysicist Nicholeen Viall on Wednesday. “This matters because it’s telling us about fundamental physical processes as this material is created and sent out into the solar system.”

Researchers have likened studying the solar wind to studying the source of a waterfall. If you can only observe from the base of the fall, the stream will be mixed and you’ll end up understanding very little. This is the view of the solar wind from Earth. With the Parker Solar Probe, scientists are able to effectively crawl up the waterfall.

“We can see that there is underlying structure, there’s intermittency, the wind is emerging in a bursty fashion from the sun,” said Stuart Bale, UC Berkeley physics professor and lead researcher for some of the probe’s instruments, in a statement.

New Data, New Records

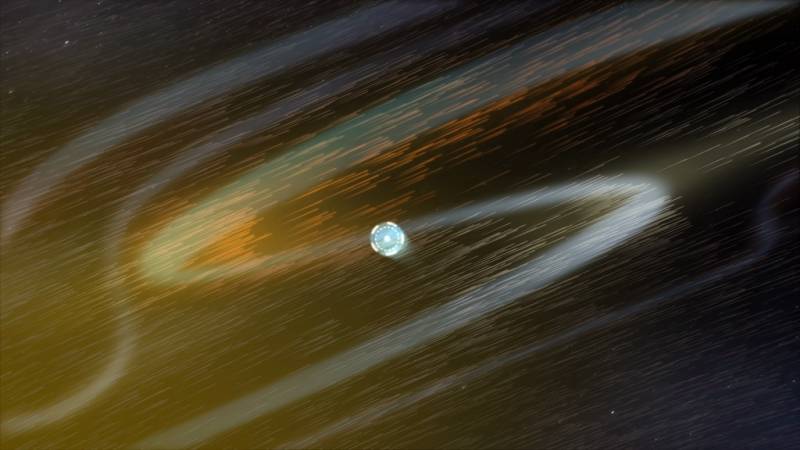

At AGU, researchers presented new images and findings hinting at the mechanics behind the sun’s spew of solar wind. Researchers characterized particles and magnetic fields in solar storms or “coronal mass ejections.” For the first time, they’ve observed these CMEs sweeping up and freshly energizing particles that the sun had spit out.

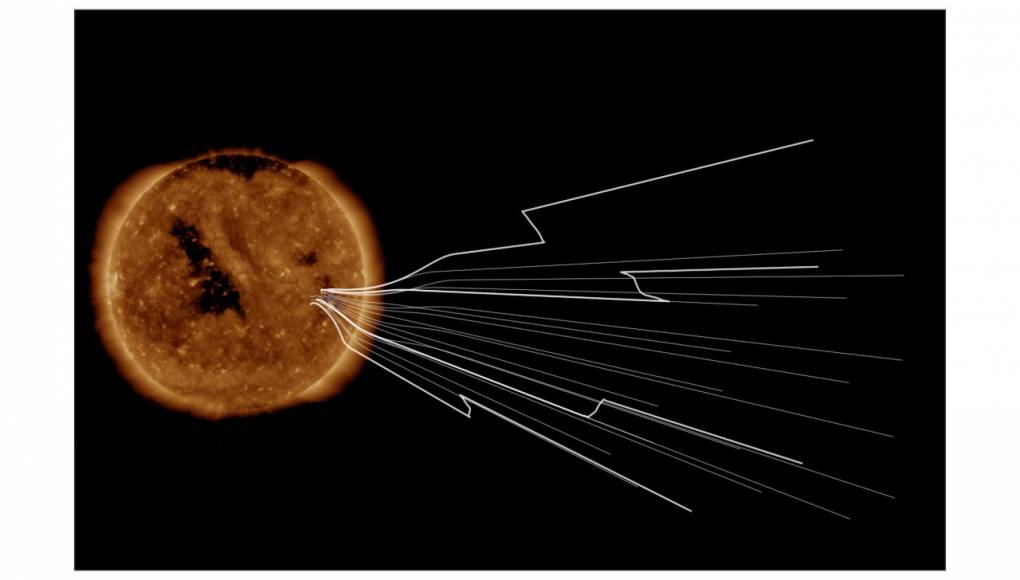

Researchers also elaborated on the Parker Solar Probe’s discovery of what scientists are calling “switchbacks,” when the solar magnetic field doubles back on itself. Researchers think these may help heat and accelerate the solar wind.

The Parker Solar Probe now holds the record for the spacecraft to pass closest to the sun, cruising about 15 million miles from the solar surface on three different passes. In 2025 it is expected to pass within 4 million miles; eventually, it will spiral into the sun and burn up. The probe is also the fastest spacecraft in history, cruising our inner solar system at about 430,000 miles per hour.