Researchers with the U.S. Geological Survey have refined their understanding of how soft basins of sedimentary rock below Earth’s surface amplify shaking from big earthquakes. The San Francisco Bay Area, Los Angeles, Seattle and Salt Lake City all have deep basins beneath them.

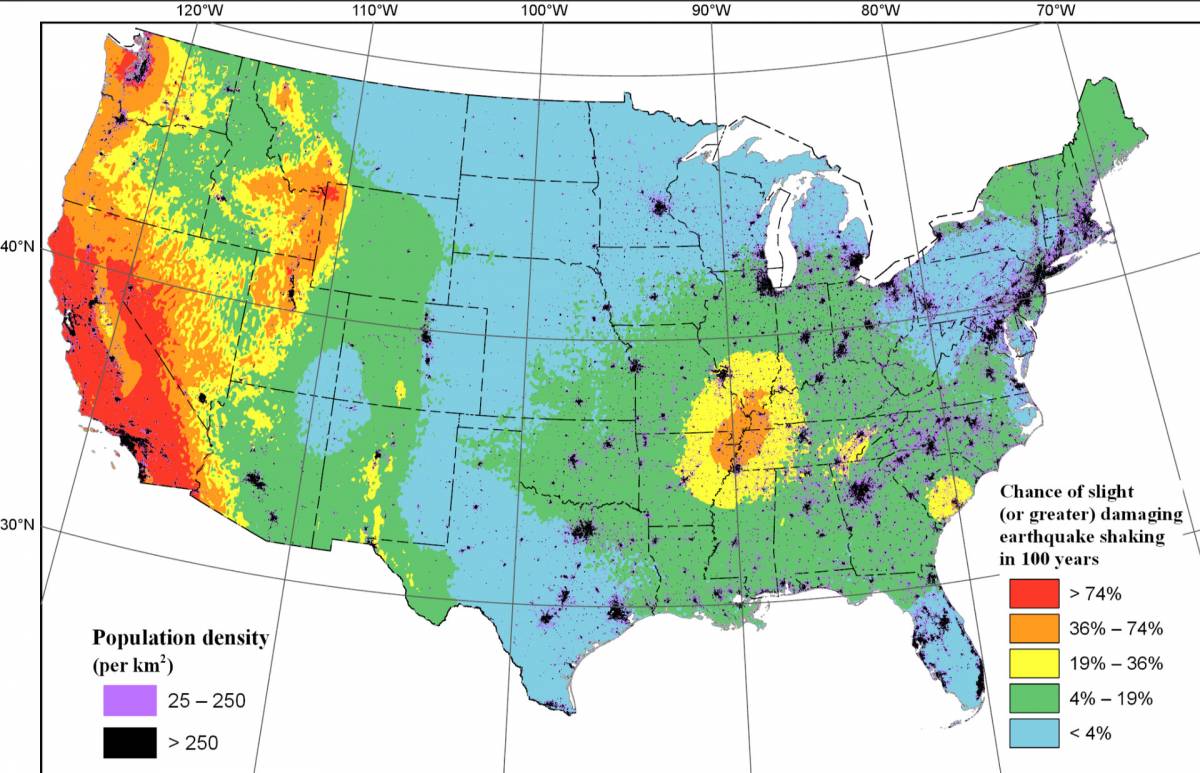

The study gives policymakers more detailed information to assess the strength of buildings during a major earthquake, and to guide homeowners in reinforcing their houses. The new estimates will be included in future building codes. The data has also been incorporated into the USGS hazard map that was released last week, and which you can see below.

Among the findings: a 25% increase in potential shaking for Walnut Creek and a 10% increase for San Jose over the last USGS hazard assessment in 2014.

Click on the map to see a larger version.

“We looked at these core areas to try and estimate how we can better account for these shaking levels beneath urban areas across the western U.S.,” said Mark Petersen, a research geologist with the USGS, who presented the study at the American Geophysical Union’s annual fall conference in San Francisco last week.