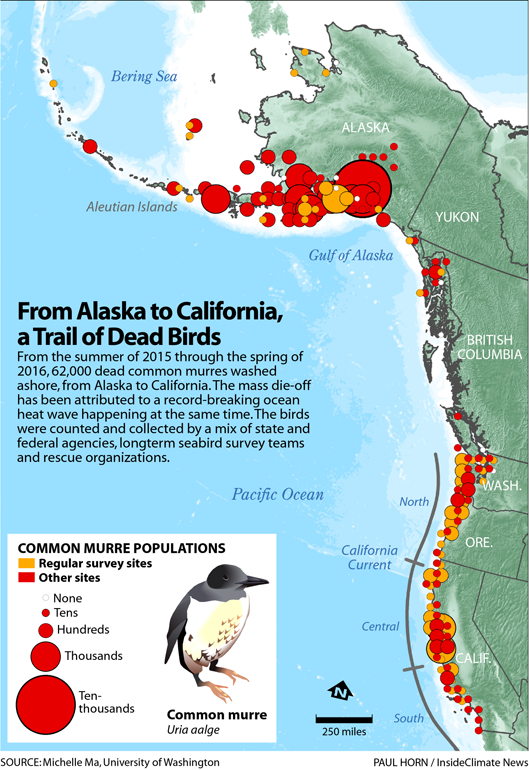

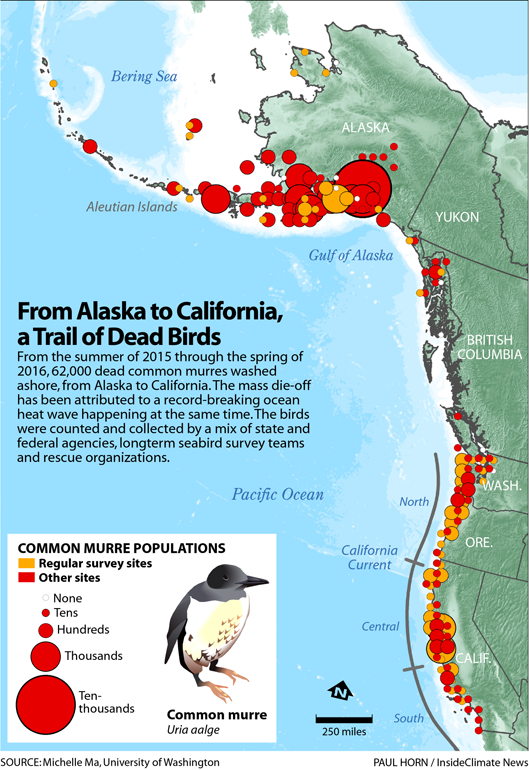

The authors estimate that 1 million common murres died during the period, an event they called “unprecedented and astounding.”

The common murres weren’t the only species to experience mass die-offs during this time—tufted puffins, Cassin’s auklets, sea lions and baleen whales died, too. But what the scientists document is by far the largest die-off, one they say was caused by disturbances rippling across the food web, a result in part of ocean warming from climate change.

Oceans are warming at a rapidly increasing pace, a study published earlier this week showed, and last year registered the hottest ocean temperatures on record. As that heat builds up, it’s having devastating consequences.

“When I heard the numbers of birds being killed in California and Oregon and Washington and many areas of Alaska, as that unfolded, it was biblical to me,” said John Piatt, a biologist with the U.S. Geological Survey who was the lead author of the new paper on the bird deaths and has been studying common murres for 40 years.

“This bird doesn’t fail unless there aren’t enough high density patches of food to serve their high demand needs. And that’s rare,” Piatt said.

The Death Toll Grows

So what happened?

As reports came in from up and down the Pacific coast, Piatt was perplexed. Common murres are known for their ability to adapt. “Murres are the ultimate predator—they’re extremely well adapted, they can dive to 200 meters, and they live on the Continental Shelf,” he said. “Anywhere along there is their domain. And they’re the fastest flying sea bird.”

Yet murres were washing in with the tides—sometimes 10 birds at a time, sometimes 100.

After Irons’ discovery on New Year’s Day, everything changed, said Julia Parrish, a biologist at the University of Washington who leads the Coastal Observation and Seabird Survey Team and was a co-author of the study. Federal agencies started to get involved and were able to fly along the coastline and send more people to conduct surveys.

Surveys in the Gulf of Alaska conducted by the Interior Department turned up more than 20,000 dead murres, and the public reported 21,435 more to the department.

The scientists reached out to bird and rehabilitation centers from southern California to Alaska and found that, out of 66 that responded, 37 reported receiving injured or dead murres—a total of 3,365 birds. The body count ticked higher.

The Investigation

The first thing the scientists needed to know was whether these deaths indicated a danger for human health. Were the birds carrying a disease? A toxin?

Carcasses were shipped to the U.S. Geological Survey’s National Wildlife Health Center in Madison, Wisconsin. “They did all sorts of analyses for viral and bacterial diseases, toxins in the tissues,” Parrish said. “We’re trying to eliminate smoking guns. But all of those things—not found. No parasites, nothing we can hang our hat on. But there was lots of emaciation.”

Like many of his peers, Piatt was aware that these deaths were happening at the same time that the ocean was experiencing a record high heat wave, exacerbated by a ridge of high pressure on the West Coast that scientists were calling “the Blob.” But still, he wondered, “What could account for a decline in the food supply from California to the Bering Sea all at the same time?”

To get the answer, the scientists started ruling things out.

The first question: Could the fish that the murres eat have moved elsewhere in response to the warmer water? It’s well understood that fish respond in specific ways when the ocean temperature changes, sometimes moving north, south or deeper down. “But the thing is, murres can go anywhere in a matter of hours,” Piatt said.

The researchers also looked into whether overfishing could be the answer, but that didn’t hold water, either.

Next, they investigated whether the fish were surviving from egg to larvae. Some juvenile stock were failing, sure, but not enough to explain the large number of starving birds.