California has also brought 23 solo challenges against the administration, which Marquette hasn’t included in its tally yet.

In total, the state has been involved in at least 77 legal fights with the Trump administration in just three years. That’s plenty more than Texas had with the Obama administration over eight years, when rising partisanship gripped the nation and conservative state attorneys general challenged the federal government in record numbers.

Republicans’ win rate against Obama hovered around 60%. Democratic attorneys generals’ rate is close to 80% against Trump.

But … the Conservative Supreme Court …

California’s win rate shows that lawyers in its attorney general’s office are bringing strong cases, says legal scholar Buzz Thompson, founding director of the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment.

“It is also true that the Trump administration has been pushing the boundaries of legitimate environmental deregulation more than any prior administration,” he said. “He has been doing it quickly and in some cases sloppily. As a result, there are a lot more opportunities to revise environmental actions.”

Paul Nolette, chair of the political science department at Marquette University, says losses are more likely if the challenges from California rise to the Supreme Court, which has a majority of strongly conservative judges. At the same time, he added, not all of the cases will reach that level.

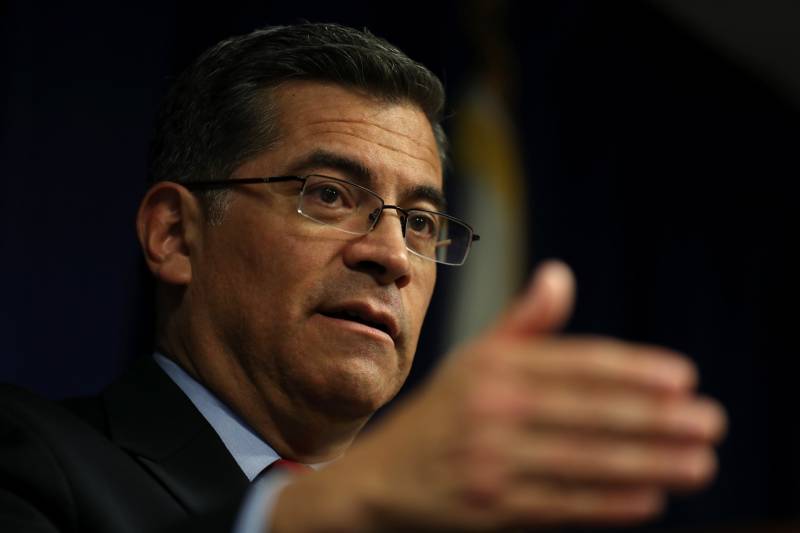

Becerra maintains that he’s “optimistic and confident” that California’s environmental challenges will be successful in the Supreme Court because of what he calls his “three allies” — facts, science and the law.

“It should be no different when we get to the Supreme Court with most of these cases,” he said.

Mary Nichols, the top air quality regulator with the California Air Resources Board, said in an interview with the L.A. Times that the environmental case she’s most concerned about is the state’s dispute with the federal government over vehicle emissions.

California challenged the Trump administration after it moved to revoke a waiver that granted authority to the state to set its own tailpipe emissions standards for cars.

“Our strategy is to win, but to win in a way that does not precipitate a Supreme Court taking of this case until Mr. Trump is out of office,” Nichols said.

Pushing Federal Policy From California

Nolette said Becerra and other state attorneys general are more involved in national policy now because new federal statutes allow them to enforce environmental policy, consumer protections, Medicaid regulations and other federal law. “Also,” he added, “lawsuits work.”

“Twenty years ago, if you said that somebody like Becerra, who was pretty high up in House leadership, is going to resign his seat and go back to California for a state position that is not governor, people would have said: ‘Why would he do that? That’s a terrible career move,’” Nolette said. “Becerra realized he’s able to get more done and get more attention for his policy agenda as the attorney general of California than he was even in House leadership.”

Becerra worked as a California deputy attorney general in the late 1980s, before voters elected him to statewide office in 1990 and eventually to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1992. He sat on the powerful Ways and Means Committee and chaired the House Democractic Caucus.

Becerra replaced Kamala Harris as California attorney general after she was elected to the U.S. Senate in 2016.

A fight over the Trump administration’s travel ban — an executive action that blocked people from six majority-Muslim countries from entering the U.S. — shows that even if a court throws out a legal challenge, the state can first extract policy concessions from the federal government.

The administration’s first travel order sparked chaos at San Francisco International Airport before the courts knocked it down. The Justice Department responded by altering the measure, and the Supreme Court reinstated it.

The Supreme Court decision was one of California’s few legal losses against this administration, but President Trump didn’t celebrate the victory.

Instead, he complained on twitter that his Justice Department “should have stayed with the original Travel Ban, not the watered down, politically correct version they submitted to S.C.”

When asked if he’s been more effective in shaping federal policy as California’s top lawyer than he was as a congressman, Becerra said he doesn’t want to “disparage my time in Congress … but it’s true, in a way.”

“This agency can be pretty nimble and move fast as compared to a legislative body, which requires a majority vote and approval by an executive to actually get anything done,” he said. “I have found that over these last two-plus years that it’s been a great opportunity to actually implement policy without having a vote.”