This Dangerous Mosquito Lays Her Armored Eggs – in Your House

Here’s something easy you can do to fight disease this spring. While the efforts to end COVID-19 have upended daily life, it may only take a few simple steps to stop the carriers of other dangerous diseases — mosquitoes.

As the weather starts to warm up in April and May, mosquito control districts across California are urging people to go through their yards and eliminate breeding places for mosquitoes that can transmit dengue fever, a painful and sometimes deadly disease that has exploded worldwide.

“Make sure you don’t have things that can hold water,” said Gary Goodman, manager of the Sacramento-Yolo Mosquito and Vector Control District. “Small children’s toys, small buckets.”

The Aedes aegypti (AY-dees ee-GYP-tie) mosquito was first reported in California in 2013. It is now established in Southern California and the Central Valley, with temperatures commonly in the 80 F to 82 F range that the mosquitoes need to reproduce.

“The Bay Area isn’t warm enough,” said UC Davis entomologist Chris Barker, who studies the mosquito, “although there are parts of Santa Clara that get hotter and might be suitable.”

The white-striped mosquito worries public health officials because its bite can transmit the four viruses that cause dengue, a flu-like illness known as “breakbone fever” for the severe pain in the joints that patients often feel. If a person gets infected a second time with a different dengue virus, the disease can be deadly.

The mosquito can also pass on the viruses that cause Zika, which can lead to birth defects, and Chikungunya, another painful joint disease.

Though none of these diseases is being transmitted locally in California, every year travelers return to the state with infections they caught elsewhere. Last year 263 California residents came back home infected with dengue from other countries.

All it would take would be for a returning infected person to land in a neighborhood where the mosquito is abundant, during the warmest part of the summer, for A. aegypti mosquitoes to bite them and spread the disease locally, Barker said.

“L.A. is the number one place where it could happen,” he said. “It’s warm, it has lots of people, it has Aedes aegypti and people who travel back and forth to Asia and Central America who have meaningful connections there.” In other words, people who might hang out in their family’s backyard.

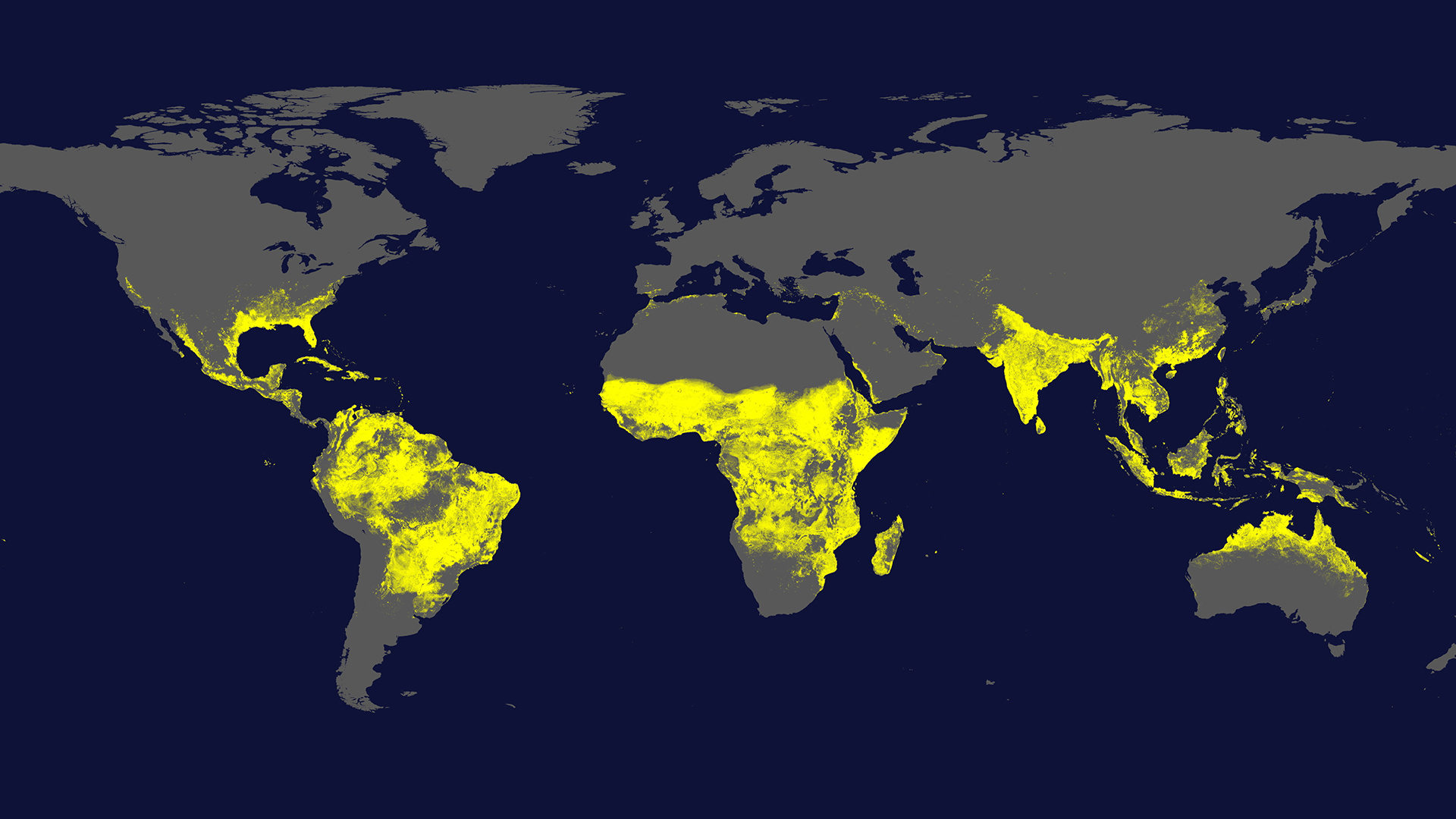

Brought on by the spread of A. aegypti, dengue cases have increased dramatically worldwide in the past 20 years, with one study estimating that close to 100 million people end up sick each year, according to the World Health Organization. Dengue is common in Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands and American Samoa. And local outbreaks have occurred in the past seven years in Hawaii, Florida and Texas, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In addition to California, the mosquitoes are likely to be found in a vast swath that goes from Texas to Virginia.

A. aegypti mosquitoes don’t fly far – maybe a couple of city blocks. They lay their eggs in and around our homes and feed mainly on humans; they’re especially attracted to ankles and the lower body.

Their ancestor mosquito, which still exists today, lays eggs in tree holes in the rainforests of West Africa and feeds on mammals other than humans. Researchers believe that 4,000 to 6,000 years ago a drought emptied out the tree holes and pushed the mosquito into villages, where they started laying eggs in water containers and feeding on humans.

“They went from being a wild species in the tropical rainforest biting nonhumans to being what I call domesticated, living closely with humans,” said Jeffrey Powell, who has studied the mosquito’s genetics at Yale.

Humans move these mosquitoes around the world by unwittingly transporting their eggs, which are drought-tolerant and travel well. While other mosquitoes — such as the common house mosquito that transmits West Nile virus in California — lay clumps of eggs on the water’s surface that need to remain wet in order to survive, A. aegypti females lay individual eggs above the water line that can stay viable for up to six months after drying out.

Sitting above the water line, the eggs absorb a little bit of moisture that the larvae inside need to develop. At the same time, the eggs darken and their outside layer turns into a thick protective shell. After three days, the eggs can dry out safely and still remain viable. The next time the eggs come in contact with water — whether from a tropical rainfall or a sprinkler in California’s Central Valley — a wriggly whitish larva will hatch from each one and grow into a winged adult mosquito.

The eggs might look like a fine line of dirt. But they’re small and hard to spot, especially if the mosquito lays them in a dark container like a discarded tire. So experts recommend dumping the water out of containers once a week, to get rid of any larvae that might have hatched. It takes larvae 10 to 14 days to grow into adult mosquitoes, so emptying containers once a week prevents them from reaching that milestone.

“No standing water,” Powell said. “Birdbaths, discarded tires, tin cans, anything, even a flowerpot. If you have a flowerpot and you have a tray underneath and you overwater and water collects in the tray underneath the flowerpot, that’s a good place for Aedes aegypti to breed.”

Because the mosquitoes make their home inside and around people’s houses, they present a special challenge to mosquito control districts. Last summer, at the end of August, the Sacramento-Yolo Mosquito and Vector Control District found the first A. aegypti mosquitoes reported in the area.

After they collected mosquitoes in four traps in the city of Citrus Heights, technicians fanned out to try to find where they were breeding. The mosquitoes that transmit West Nile virus are found in rice fields and catch basins, while A. aegypti’s breeding places are harder to locate because they’re varied and smaller.

“One of our technicians was going up to a door. They looked down and on the porch the resident had a watering can for their flowers,” said Goodman, the district’s manager. “They noticed in that watering can an adult mosquito that was flying. And that’s where we found one of the breeding sites for the Aedes aegypti.”

In October, the district traced another small outbreak of the mosquito to an ornamental plant known as a lucky bamboo — which isn’t really bamboo, and in this case, wasn’t lucky either. A resident of the Sacramento neighborhood of Pocket-Greenhaven had received the plant as a housewarming gift from someone who bought it in Ontario, in San Bernardino County, an area known to have the mosquitoes. When technicians took the plant back to the district’s lab, they discovered larvae floating in the water in the pot. The mosquito had laid eggs on the inside of the pot and on the gray rocks the plant was wedged in.

No mosquitoes have been found in the neighborhood since the plant was removed. But the finding is an example of how the mosquitoes get around and breed in places where they go unnoticed. Goodman said it’s especially important to pay attention that the water from sprinklers isn’t collecting in places like drainage pipes. If you notice adult mosquitoes buzzing around, give your district a call.

And one more thing. “Use a good repellent,” he said. “Because if you’re not bitten by a mosquito, then the risk of transmission of disease is eliminated.”