Even before the worldwide outbreak of novel coronavirus, we were all familiar with social distancing and other practices to prevent the spread of disease in society: Staying home from work when sick; coughing into our arms; getting an annual flu vaccination.

But did you know that NASA has been engaged in these practices, on an interplanetary scale, for decades?

Planetary Protection

NASA’s Office of Planetary Protection has established policies for preventing the transfer of terrestrial microbes and organic materials to other planets and moons in our solar system, as well as the protection of Earth from extraterrestrial organisms that might be carried back.

These policies are designed to mitigate accidental cross-contamination by missions of exploration where a “stay-at-home” approach just doesn’t work. These practices include:

- Building sterile, or “low biological burden,” spacecraft to minimize the possibility of terrestrial microbes and organic material “hitchhiking” to other worlds

- Designing flight plans that prevent physical contact with other bodies in the solar system

- Creating plans for handling collected samples that have been brought back to Earth for laboratory study, in order to prevent extraterrestrial organisms — if they exist — from contaminating Earth’s biosphere.

Ensuring Astronauts Don’t Pick Up an Astro-bug

In the early days of solar system expeditions, there were many unknowns with respect to extraterrestrial life — the biggest being, of course, is there any?

The idea that the moon might harbor some form of contagion, though considered unlikely, prompted NASA to quarantine the astronauts of Apollos 11, 12 and 14 by housing them in special isolation trailers for three weeks following their return.

One of these trailers is currently on display at the USS Hornet Museum in Alameda — though, ironically, you can’t go there right now because of our current quarantine.

To this day we have not detected evidence of life beyond Earth, but we have learned a lot more about how terrestrial life has adapted to living under very extreme conditions on our planet.

“Extremophile” life forms thrive in Earth’s coldest, darkest, hottest, and most toxic environments — on the deep ocean floor, around geothermal hot springs, under Antarctic ice. Their adaptability and tenacity both encourage and caution us that life might be found on other worlds in our solar system, and tell us that we must take great care in exploring them.

Mars Vehicles Sterilized

Mars’ surface is now home to nine retired and still serving robotic landers and rovers, as well as a few derelicts and the wreckage of unsuccessful landings.

Before leaving Earth, these vehicles were painstakingly sterilized to prevent the inadvertent transfer of terrestrial extremophiles.

Why?

First, because if there is indigenous Martian life — perhaps thriving in wet, underground environments — we don’t want to introduce an invasion of Earthling microbes that might cause a Martian pandemic. It would be a disaster if we accidentally wiped out organisms that have managed to survive Mars’ cold, dry environment for billions of years.

The other reason not to contaminate Mars, or any other world we explore, is simply so that we don’t interfere with our search for life there. A robotic explorer carrying a sensitive life-detecting experiment might produce confusing results if it detected terrestrial extremophiles instead.

Incinerating Spacecraft

Planetary protection also includes spacecraft never intended to land on other worlds.

The Galileo spacecraft in the Jupiter system and Cassini at Saturn weren’t designed to land on anything, but they could have eventually run out of fuel needed to maneuver, becoming derelicts that might one day crash into a moon.

Because an astounding outcome of both missions was the discovery of moons that possess liquid water, and the tantalizing possibility of life-harboring environments, NASA sent both spacecraft on fiery plummets into Jupiter and Saturn’s atmospheres, incinerating any possible biological material that could have contaminated those moons.

Speculating on the Damage From an ET Virus

What would an extraterrestrial organism do to us if it were to contaminate Earth’s biosphere? The answer, of course, would depend on the nature of the organism, and if it could even survive in Earth’s environment.

Science fiction writers have taken stabs at speculating such an event.

Michael Crichton’s “The Andromeda Strain” dramatically envisions the arrival of an extraterrestrial pathogen on Earth, and scientists’ heroic efforts to curtail a pandemic that would dwarf the current COVID-19 crisis.

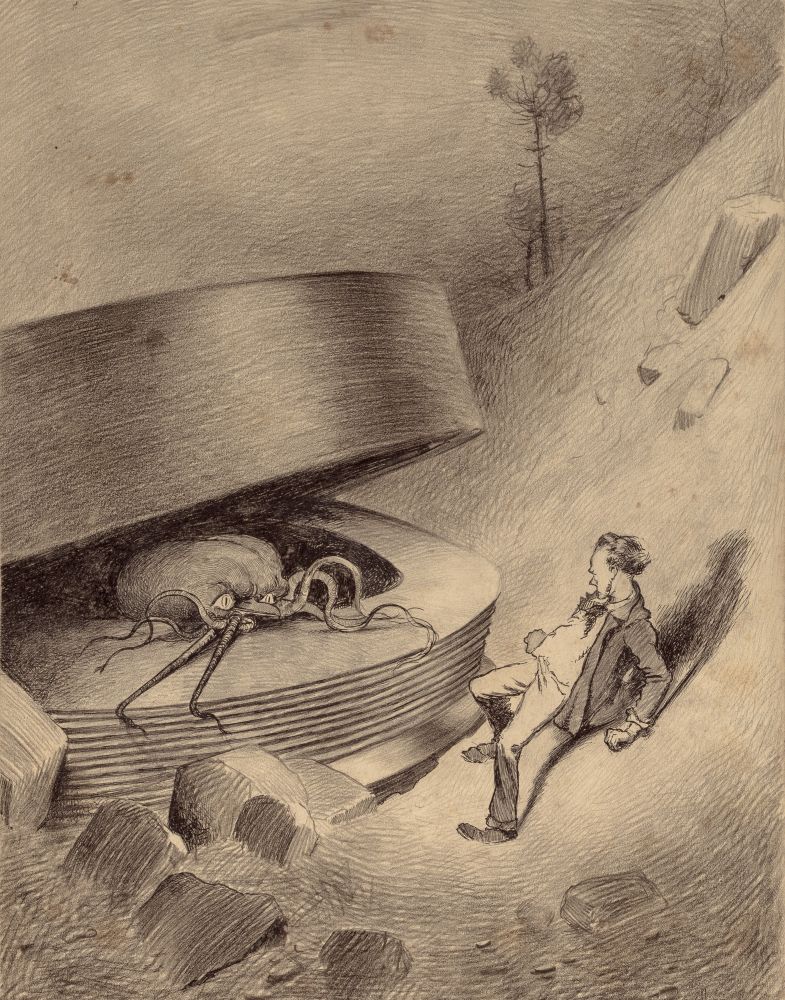

H. G. Wells’ novel “The War of the Worlds” takes a reverse approach to the idea of interplanetary contamination when an invading armada of Martians is ultimately destroyed by their lack of immunity to terrestrial microbes.

So, while we continue our safe social distancing and stay-at-home efforts against terrestrial bugs, we can find some comfort in NASA’s own safe solar-system exploration practices.