California doctors are diagnosing anything from appendicitis to strep throat with only a phone during the coronavirus pandemic. Video visits and conversations are the closest doctors can get to patients who are sheltering in place and avoiding potential exposure from doctor visits.

Telehealth Is Having a Huge Moment During Coronavirus Crisis

COVID-19 has catapulted telehealth — those virtual visits — into the mainstream more effectively than years of advocacy and policy-making. Experts and physicians are calling it a rare “silver lining” of the current crisis: An overnight availability of video and phone appointments for medical needs, especially in areas where doctors have been in short supply.

“COVID-19 has changed everything,” said Dr. Mark Henderson, professor of internal medicine and associate dean for admissions and outreach at UC Davis School of Medicine. “Because of COVID-19 we have all of this distance and it has accelerated all of these ideas and it’s totally exploded our thinking around what we can do with telemedicine in primary care.”

Telehealth has been in use for decades, long before smartphones or tablets, and California already was poised to expand options under several new laws passed last year. Initially, though, it was seen as a tool for rural communities and inner-city areas with a shortage of providers.

It took a change in regulations affecting billing during the pandemic to allow a dramatic pivot to telehealth, as much as 40% to 80% of patient visits in some health systems in recent weeks. The Department of Managed Health Care announced March 18 that all health plans must reimburse telehealth medical care at the same rate as face-to-face appointments, and California’s Department of Health Care Services obtained a federal waiver to allow similar Medi-Cal reimbursement. The federal government eased regulations on March 17 affecting Medicare payments to allow the same flexibility.

Medical providers say telehealth is especially important during the pandemic, allowing doctors to keep tabs on fragile patients, especially those with chronic conditions who are most vulnerable to falling ill from the coronavirus.

From Convenience to Necessity

Health systems that serve rural and inner-city areas already were investing in telehealth infrastructure to try to bridge the doctor shortage gap. Riverside County in the Inland Empire has only half the physicians it needs, for instance, so telehealth was one way to provide medical care in far-flung corners of the county.

Riverside University Health System, the county’s public health network, had offered limited primary care telehealth for patients facing transportation, childcare and work schedule problems. But telehealth mostly was used by behavioral health teams and those caring for incarcerated patients.

That’s changed. In the past week, the system’s medical center and 13 community health centers have handled 5,600 virtual visits by phone or video, accounting for two-thirds of all patient visits.

“This challenging situation right now has shown how telehealth can help us provide the right care in the right setting at the right time for people,” said Dr. Geoffrey Leung, chair of the family medicine department and ambulatory medical director at Riverside University Health System. He called the ingenuity behind telehealth “one of those silver linings during this difficult time for all of us.”

While Kaiser Permanente has had a telehealth program in place for years, under pandemic restrictions about 80% of the system’s appointments nationally are for video or phone calls.

“In the past, a lot of what we thought of in respect to telehealth was offering our patients choice and convenience,” said Dr. Edward Lee, the physician leader for telehealth at Kaiser Permanente. “Nowadays, because of COVID-19 and the shelter-in-place order, a lot of patients are seeing this as a necessity.”

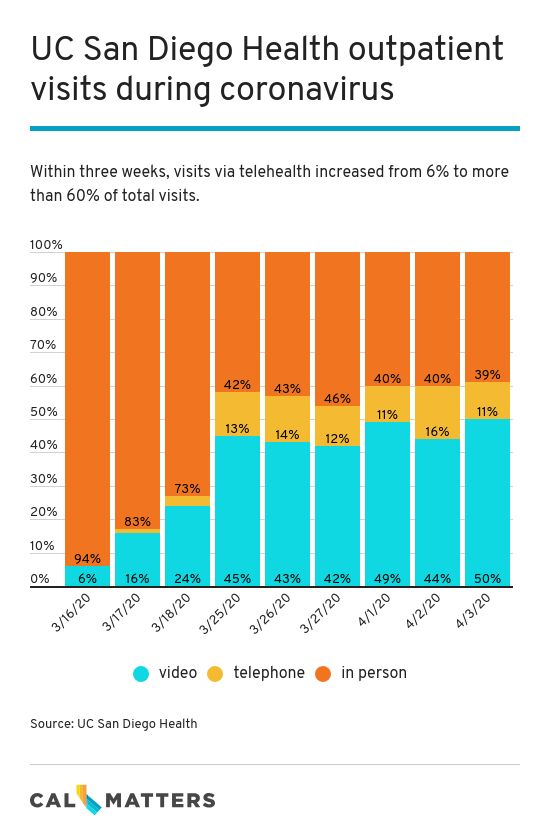

Similarly, at UC San Diego Health, about half of all outpatient visits in recent weeks were through video, said Dr. Christopher Longhurst, chief information officer for the health system. Prior to the coronavirus outbreak, UCSD Health already had a well-established telehealth system in place, but still only about 1% of their outpatient visits were handled virtually.

“We did more video visits in the first three days of rolling it out broadly (during pandemic) than we had done in the previous three years,” Longhurst said.

Not all providers, however, were as experienced in the world of telehealth as Kaiser or the UC medical centers. Many didn’t have the infrastructure set up, administrators said, and others didn’t get reimbursed for telehealth visits prior to the pandemic. In underserved communities, some health clinics were not allowed to charge Medi-Cal for telehealth appointments until the requirement was waived because of the coronavirus.

AltaMed, a health center with sites in Los Angeles and Orange counties, began video and telephone visits on March 16, just days before the state issued its stay-at-home order. AltaMed had to spread the word quickly to let patients know they could keep their appointments, they would just look different.

Dr. Efrain Talamantes, medical director for the AltaMed’s Institute for Health Equity, said that for patients who didn’t have this option in the past, telehealth is a big deal.

“It’s allowed us to care for people in their own homes, so they can stay safe, they don’t have to take time away from their family or work and we can still make sure they have the care and medication they need,” Talamantes said.

A California law starting next year ensures at least some telehealth appointments will continue to be reimbursed at the same rate as in-person visits after the pandemic. Talamantes doesn’t yet know the impact on his clinic, he said, but thinks the coronavirus shows how useful remote services can be in communities with strapped resources and high poverty. Still, it doesn’t work for every type of visit — you can’t really do a physical exam over the phone, you can’t feel a bump or administer vaccines.

Henderson, of UC Davis, who described himself as a telehealth skeptic before the coronavirus, has been pleasantly surprised by how much can be done via video, such as examining a skin rash or a healing wound and assessing breathing or the color of a patient’s skin.

“I believe strongly in the power of putting your hands on a patient, the connection you form with patients when you lay your hands on them, that to me is something very fundamental and sacred in some ways,” he said. “But that doesn’t mean there isn’t a bigger role for telehealth.”

Being able to see the patient via video makes a huge difference, he said.

“It’s a whole new world when you can see them and they can see you. There are nonverbal clues that are visible and you can use to make a connection,” he said. “The video visit adds life to it.”

Telehealth also helps to screen patients for the coronavirus. UC Davis Health expanded its telehealth capacity as a way to check in with those who might be infected, Henderson said.

Medical providers across California have been screening patients suspected of possible COVID-19 infection using video and the phone and, if they meet testing criteria, directing patients to urgent care centers, emergency rooms or testing facilities such as the temporary tents set up in some clinic parking lots.

“We didn’t want them to come in, we wanted to figure out what they looked like and if they had symptoms,” Henderson said.

Keeping Offices Afloat

Even with the new payment rules for telehealth, medical visits are down across California. Health centers and private practices are struggling to stay open; for them, a drop in appointments means a drop in revenue. The California Primary Care Association, which oversees nearly 1,400 health centers in the state, has said that clinics are losing about $90 million a week collectively during the pandemic.

Dr. Sumana Reddy runs Acacia Family Medical Group, a private practice with offices in Salinas and Prunedale in Monterey County. She said she’s scrambling to apply for every option to keep her business afloat, from loans for small businesses to advances from insurance providers.

“We’re working really hard to do what’s right by our patients and community and yet of course the irony is that it can lead to cash flow challenges,” Reddy said. “We were struggling to meet our payroll this last time.”

Full payment for telehealth patient care is a big help, she said.

“Without that I’m not sure what we would do,” Reddy said. “We made such a rapid pivot that we went within two weeks of never having even thought of telehealth to doing over 75% of our patients’ visits by telehealth.”

But video visits aren’t always the most efficient. Technology can be a barrier, especially with frail patients. Helping patients conduct a video visit is time and labor intensive.

“Imagine someone who is 80 years old, with pain, he has to look for an assistant to hold the phone, and we’re asking can you move the phone around to see the area. The entire process is so much slower,” she said. “It sounds like you could just replace a regular visit with a telehealth visit but actually there are many barriers there.”

While telehealth is necessary during these times, it can’t solve all of the issues, she said,

Rural California Still Needs Broadband

Medical providers in rural California are familiar with the technological barriers. Madera Community Hospital serves a region of California’s San Joaquin Valley with a 106-bed hospital and several community clinics. Telehealth there is mostly in the form of phone calls because many patients don’t have access to a smart phone or computer.

“We’re finding many patients don’t have fast enough internet to even do a telehealth visit,” said Karen Paolinelli, CEO of Madera Community Hospital. “When you take care of patients from all walks of life and different age groups, not everyone has the technology.”

But for those who can participate in a video visit, it helps with another big issue in rural areas, and that is transportation.

Paolinelli said she believes COVID-19 will forever change how they provide care.

“I don’t know that we can go back,” she said. “To have different ways to see patients — that’s access to care.”

Mei Kwong, executive director of the Center for Connected Health Policy, The National Telehealth Policy Resource Center, said the data from this period about how to use telehealth, when it is best and for whom, will be invaluable in creating a roadmap for the future.

“The genie is out of the bottle and you can’t let it back in, people have experienced this,” she said. “Not everybody is going to like it and people are going to want to see their providers but the option should be there.”

CalMatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.