The reduction in carbon emissions has put the world on an early track to meet a target outlined in the Paris climate agreement, which was designed to avoid a 1.5 C rise in global warming and even more severe environmental consequences. In November, the United Nations said emissions had to drop at least 7.6% per year through 2030 if the world was to have a chance of meeting the goal.

The burning of fossil fuels for heat and energy is the main source of carbon dioxide, and the steep drop in demand for energy due to whole economies shutting down is the primary factor behind reduced emissions during the pandemic.

Less impactful on a global basis is the sharp decline in driving and flying.

In California, however, the reduction in driving has a bigger impact because the state already requires its investor-owned utilities to use renewable energy, a mandate that led to a reduction of its carbon emissions below the 1990 level two years ahead of schedule.

California’s energy efficiency standards are among the strongest in the country, and its landmark cap-and-trade program requires companies to pay for the right to emit greenhouse gases while lowering the overall limits on emissions over time.

An Intractable Problem

Reducing the amount of time Californians have to spend driving is the state’s climate white whale.

For three decades, California has tried and failed to significantly reduce transportation emissions with policies that require cleaner gasoline; promote public transit and dense urban development; restrict tailpipe pollution; and incentivize the use of electric vehicles. Transportation-related emissions still haven’t peaked, and they’re the leading source of greenhouse gases in the state.

Mary Nichols, the state’s top air regulator, admitted the state’s failure on transportation emissions to Reuters last year. “The strategies that we’ve used up until now just haven’t been effective,” she said.

The seemingly intractable problem of vehicle emissions stems in part from decades-old urban planning decisions that allowed Los Angeles and other communities to build sprawling suburbs of single-family homes, one reason that so many workers are now forced to grin-and-bear hourslong commutes.

Before the pandemic, the state was falling behind on meeting its 2030 target of reducing carbon emissions by 40% from 1990 levels, according to a study by Beacon Economics commissioned by Next 10, a nonpartisan, nonprofit organization that works on economic and environmental issues.

A key problem: more Californians driving more miles in less fuel-efficient trucks and SUVs.

The UC Davis Road Ecology Center report found that the shutdown order has, at least temporarily, put the state on track to reach this target.

Tele-Everything

During this stay-at-home period, it’s not just workers in offices and other places of business who have been subtracted from streets and highways.

Visits to medical offices are way down as patients and doctors have been forced to make massive use of telehealth tools for diagnoses. Since schools are closed, no one is taking their car to drop off their kids, instead relying on whatever distance learning capability their districts are offering.

Academic conferences have moved online, too, which some organizers say could become the new normal as virtual meetings present an opportunity to reach a wider audience while reducing the carbon footprint of an event.

Kate Gordon, director of the Governor’s Office of Planning and Research, says this mass, unintentional experiment in staying home has highlighted an argument climate advocates should pay attention to.

“For a long time, we have been saying, we need to think about broadband and telework as opportunities to reduce vehicle miles traveled,” she said. “And that connection has not been as clear in the mind of a lot of climate policy people.”

Traditionally, Gordon says, it’s electrification that has been the solution of choice for decarbonizing the transportation sector.

“I think a lot of people go immediately to: ‘Oh, if we just had only electric cars, and everything would be fine,’” she said. “But what we’ve found in looking at the models is that you actually really do have to reduce the amount that people have to travel around the state because it has all these other associated emissions impacts, as well as being high polluting.”

Across the country, internet usage surged when states began ordering people to stay at home. Network providers reported a rise in usage of 20-35% in the end of March and early April, according to the Federal Communications Commission. Much of the spike stems from increased demand in suburban, exurban and residential areas during daytime hours, likely from people who can log in and work from home.

Gordon says California can support telecommuting by increasing broadband access and making nuts-and-bolts administrative changes that allow people to attend parole hearings, visit the DMV or perform other government functions online.

When the economy opens up again, she thinks, the state can sustain some of the emission reductions by investing in systems that promote telecommuting, teleconferencing, teletrips … basically, tele-everything.

“The more options people have to not do their long commutes, the better for air quality and the better for our overall emissions profile,” she said. “Universal fast internet access is part of what makes teleworking even possible.”

Digital Divide

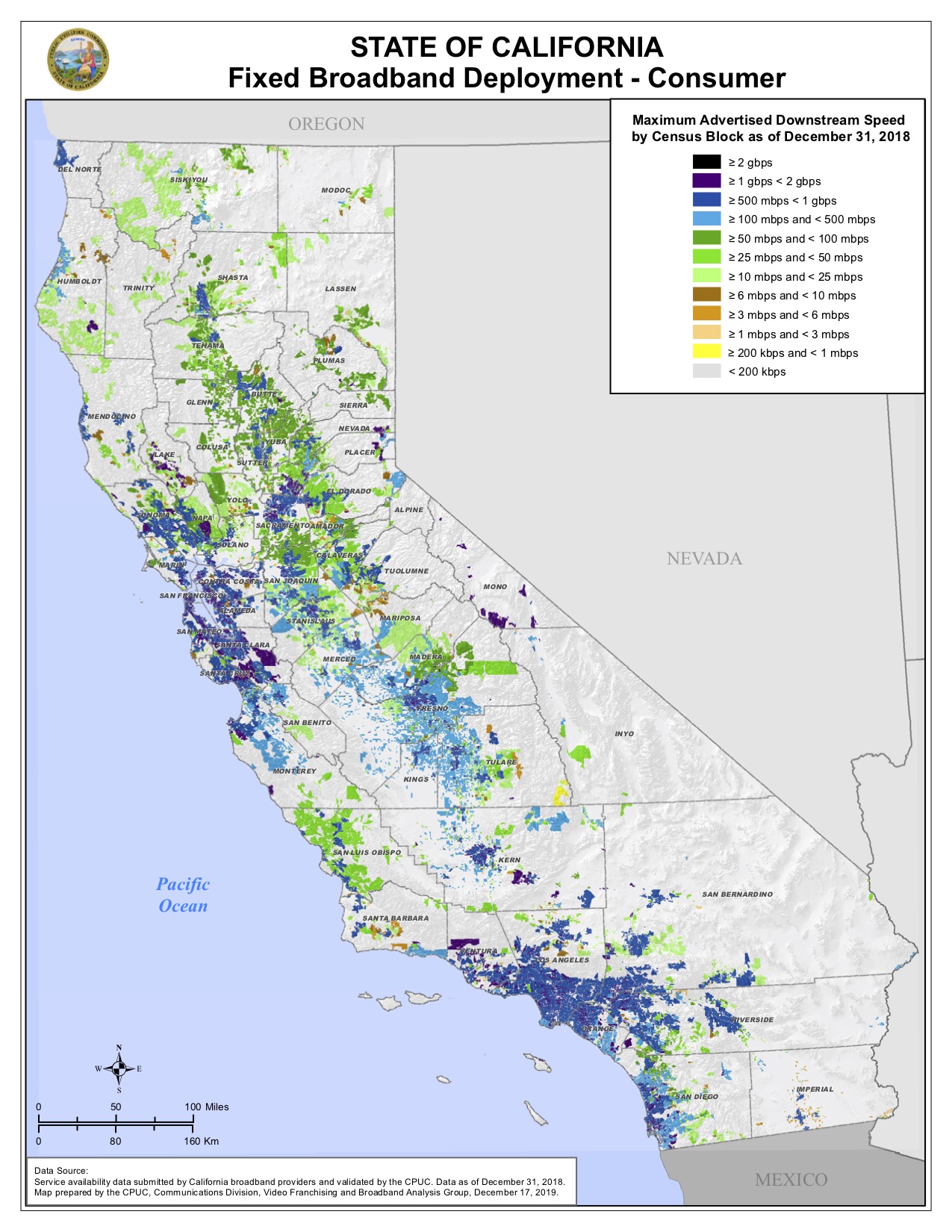

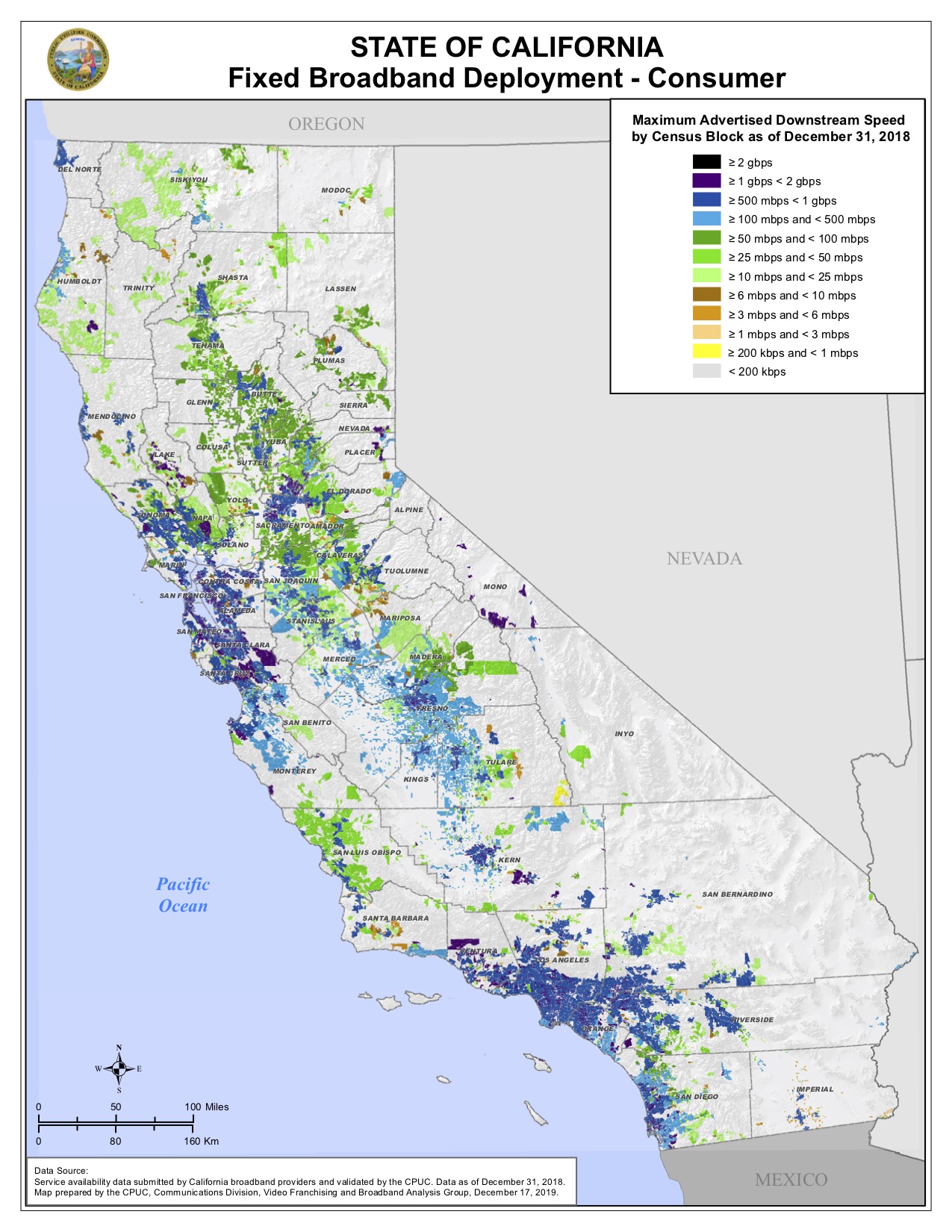

One roadblock to a tele-everything California is that it suffers from a vast digital divide, with high-speed internet access available in many of the state’s bustling urban centers, but not in remote areas in Northern California, the Central Valley and Inland Empire.

Before the pandemic, people who could telecommute tended to be white-collar workers with higher incomes, and that has held true during the pandemic, according to a Brookings Institute report.

Nowhere is that divide felt more acutely than in the schools. For example, Oakland has been offering online classes for weeks, but many students there still lack access to the internet.

Businesses Adapt

During the shutdown, businesses have found new ways to keep the economic train lurching forward, says Rufus Jeffris, senior vice president of communications for the Bay Area Council, an advocacy group that has long pushed for policies to reduce solo commuters on roads and freeways.

Those who have fast internet setups have been able to adapt to working from home, leaning on an ever-growing roster of video conferencing applications like Zoom, which has seen its stock price soar during the pandemic, from $68.72 a share on Jan. 2 to a peak of $181.50 on April 24.

He said although it will be “interesting to see whether this cements work-from-home practices more broadly,” he doesn’t think telecommuting can substitute for the office.

“Business and the economy are taking a big hit right now,” he said. “We have to figure out how to save lives, but also save livelihoods. Businesses want to follow the public health and science behind this, but business leaders are eager to get to work and start figuring out safe ways to reopen as soon as possible.”

Sunrun, a leading residential solar company, is one business that has been able to change its work protocols to stay operational.

Getting a solar unit onto a customer’s house usually begins with an employee scouting a home to site solar panels. Now, it’s the customers who are snapping their own photos with smartphones, sending them in to the company in an effort to limit human contact, says Anne Hoskins, Sunrun’s chief policy officer.

Instead of submitting permitting documents to planning departments in person, company representatives send them electronically.

“We even went a step further with some of the permitting offices and said, ‘We think you could do the inspection remotely. We can do it by camera and with you on the other side.’ And some offices agreed to that, as well.”

Hoskins thinks this remote work could speed up the process and improve government permitting even after the stay-at-home orders are lifted.

What Happens After State Order Lifted?

Which experiments in telecommuting will be maintained on a widespread basis after people eventually go back to some semblance of their pre-pandemic lives remains to be seen.

In the back of the mind of UC Davis’ Shilling is a “nascent irritation” that California is “going to reverse path and take us right back to the place we were before and not learn these lessons,” he said.

He says his colleagues express this cynicism when he talks about the

“optimistic projection” that the state can use this moment to change driving behavior.

“They say: ‘Oh, no, we’re just going to go back to what we were doing before,’” Shilling said.

But this is too fatalistic, he says.

“It’s kind of like running along the edge of a cliff,” he said. “Because that’s essentially what we’re doing as a species and as a society. And if you just have this idea, I’m going to fall off the cliff and die, then you may increase your chances of doing that.

“But if you are more optimistic and say: ‘I’m not going to fall, I’m going to try really hard to not fall off the cliff, then maybe you’re more likely to succeed. To me, being optimistic is a better survival strategy.’”