“There will definitely be cars, passenger vehicles, in multiple segments where the EV option is the cheaper option,” Viswanathan said about the 2025 time frame.

When we talk about the cost of EVs, we’re mainly talking about the cost of batteries, which are the most expensive components in the vehicle, and also the ones for which the costs are changing most quickly.

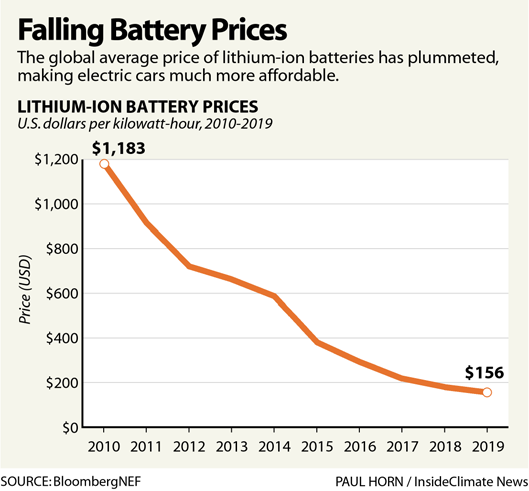

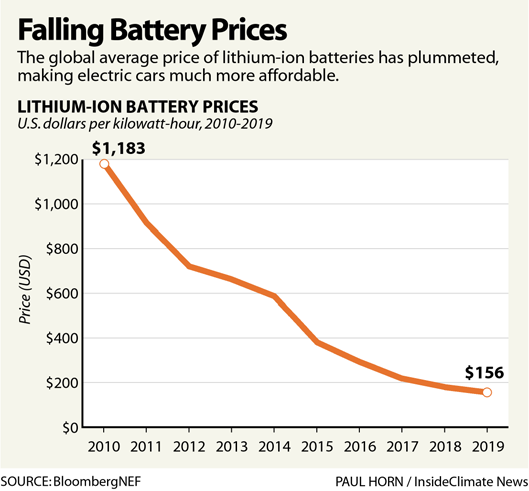

Analysts and researchers have said for years that a battery price of $100 per kilowatt-hour is the point at which EVs become cost-competitive with gasoline vehicles. Last year, the global average price was down to $156 per kilowatt-hour, according to BloombergNEF.

But the model developed by Viswanathan and his colleagues shows that battery packs are on track to cost less than $80 per kilowatt-hour by 2025, a projection in line with leading forecasts, like that from BloombergNEF (You can read more about their model in a 2017 journal article and in a recent post on The Conversation).

Now that the below-$100 benchmark is within sight, it’s important to specify what it means. It doesn’t mean that I can go out and buy an EV of any size and it will cost the same or less than it would for a gasoline model with similar features. But it probably does mean that I will be able to get a compact sedan EV for about the same cost and with similar features as one that runs on gasoline.

Viswanathan said cost parity will arrive first for small sedans that now sell for $30,000 or less. It will take longer for automakers to develop electric trucks and SUVs that cost about the same as similar gasoline models.

One of the big reasons we will need to wait longer for larger vehicles is that trucks and SUVs need a lot of power for towing capacity, which means larger battery packs and higher costs.

The fact that EVs will be cost-competitive should help to transform a market in which less than 2% of new vehicles sold are all-electric.

This change is coming, and it’s coming fast, and that’s good news for the climate because transportation is responsible for more than a quarter of U.S. emissions.

Electric Trucks Are Coming, with Chevy Entering the Fray

Most of the EVs on the market today are sedans, even though U.S. consumers prefer, by a wide margin, crossovers, trucks and SUVs.

Automakers know that for EVs to truly reach the mainstream, there will need to be attractive options in all of those classes, which is why several of the biggest players are racing to develop all-electric pickups.

General Motors said last week that it will begin selling an all-electric Chevrolet pickup by 2025. This will follow the company’s release of the GMC Hummer EV, a pickup that could go on sale as soon as next year.

Those models will be part of a competitive landscape that also includes the Ford F-150 EV, the Tesla Cybertruck and the Rivian R1T, all of which are heading for rollouts over the next two years.

Stephanie Brinley, an auto analyst for IHS Markit, told me that automakers are developing electric trucks not because they expect to sell a lot of them in the near future, but because they need to have strong electric options across their lineups in the long run.

“You can’t wait until 2040 and go, ‘Oh, now we’ll just drop the battery in here,'” she said. “The vehicle needs are too complicated, so you have to start developing it much earlier.”

Her company is projecting that all-electric trucks will be 0.87% of U.S. sales of cars and light trucks in 2025, and that EVs in general will be about 8% of sales.

One of the big questions about electric trucks is which regions will emerge as centers of customer demand. Brinley said she is looking to Texas as a possibility because the state is the leading market for pickup trucks. California is also likely to have a big role to play, she said.

But even in those places that have demand for electric trucks, that demand is likely to be low.

“We’re really in baby stages,” Brinley said of building the foundation of the market to come. “It’s not about how many you sell in 2024. It’s about how many you sell in 2035.”

Reporter Nicole Pollack contributed to this story.