Since early in the pandemic, scientists have said antibodies that the immune system makes to fight the coronavirus could be crucial in finding a cure for COVID-19.

The FDA recently authorized one of these treatments — convalescent plasma, in which the antibody-rich portion of blood donated by recovered COVID-19 patients is given to people hospitalized with the disease. But the approval, which came soon after President Donald Trump accused the agency of moving too slowly on the treatment for political reasons, has prompted pushback from some in the scientific community, who say more research is needed to determine if and how plasma can be effective against COVID-19. Meanwhile, research on another therapy, involving antibodies cloned in the lab, is just getting underway in human subjects.

‘Liquid Gold’

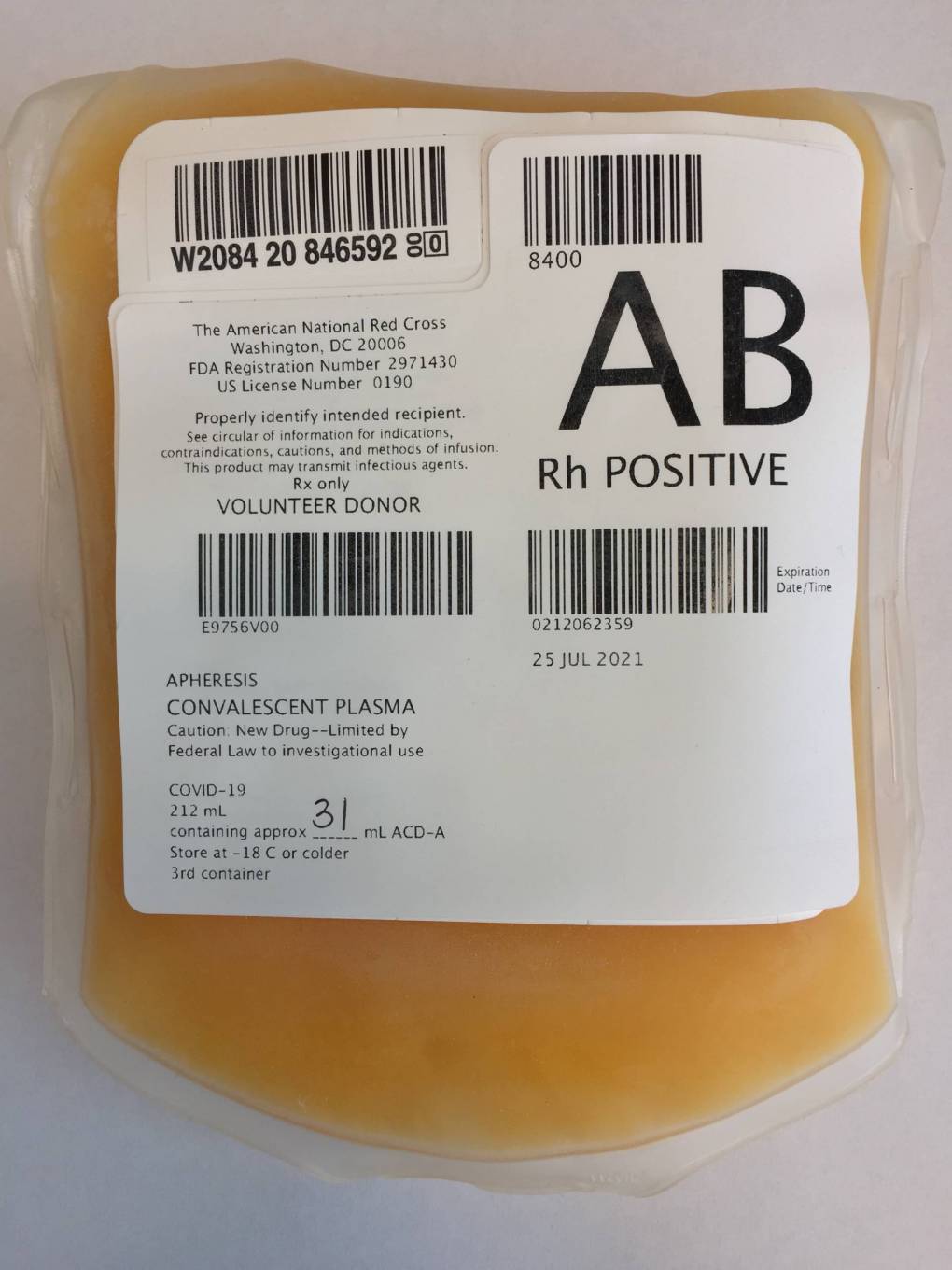

Plasma, sometimes called “liquid gold” by doctors for its yellow hue and potential therapeutic value, is made by spinning blood to separate antibodies and other proteins from red blood cells.

The use of convalescent plasma in medicine dates back more than a hundred years.

“We’ve used it in infectious diseases from polio to influenza, ebola, etc.,” said UCSF professor of medicine Dr. Peter Chin-Hong.

Chin-Hong, whose team is running a COVID-19 convalescent plasma trial, says that while the treatment is considered relatively low-risk, the FDA’s authorization is too hasty.

“The main reason why it’s the wrong time is that we just don’t have enough data yet to say if it works,” he said.

Early results from a Mayo Clinic study suggest convalescent plasma may reduce COVID-19 mortality rates. But the study, which is available as a non-peer-reviewed preprint, wasn’t placebo-controlled, and Chin-Hong says results from rigorous clinical trials with COVID-19 convalescent plasma have yet to be published.

“I think plasma is a great potential intervention,” he said. “I just don’t know where it works best.”

The FDA’s authorization limits plasma treatment to hospitalized patients, and much of the early application for research purposes has focused on the most severe cases. But Chin-Hong says convelescent plasma may work better early on, before the disease has a chance to progress and patients get seriously ill.

Dr. James Zehnder, director of clinical pathology at Stanford, agrees that the jury is still out on whether plasma can treat the sickest COVID-19 patients. In looking at the natural patterns of how infected patients make antibodies, he says, researchers have seen the most robust antibody response from those who have severe, potentially life-threatening inflammation. In contrast, those who have milder illness tend to have a weaker antibody response.

“So one question is that if the really sick patients are already making really high levels of antibodies,” Zehnder said, “how does infusing more antibodies help?”

Results from placebo-controlled trials, Zehnder says, are the gold standard for clinical research, and they will be key in answering questions surrounding COVID-19 convalescent plasma therapy.

Dr. Stuart Cohen, chief of infectious diseases at UC Davis, worries that a broad rollout of the treatment in the wake of the FDA authorization could jeopardize that research by stifling enrollment.

“If I tell you, you can be on this clinical trial where you could get a placebo and then they say, ‘Well, I saw that this is available already, why don’t you just give it to me?’” Cohen said, “that sort of finishes off any real ability to determine whether this really works or not.”

While he acknowledges doctors are desperate for more tools to try to fight COVID-19, Cohen cautions that the supply of convalescent plasma, which has mostly kept up with the demand for research studies, could be depleted as a result of the FDA authorization.

If doctors all of sudden begin prescribing the drug liberally, Chin-Hong adds, “it may mean that the patients who need it the most may not get it.”