Growing Concern About Health Risks From Wildfire Smoke

More than a dozen studies have emerged from around the world in recent weeks on how air pollution affects COVID-19, but many urgent questions remain. Will I get sicker from the coronavirus because I inhaled so much wildfire smoke for so long? Am I more likely to die from COVID-19 because I live downwind of these massive wildfires? As a coronavirus survivor, am I more vulnerable to wildfire smoke? Does wood smoke harm my health even more than urban pollution?

“When it comes to how we might expect wildfire smoke to exacerbate COVID-19 risks, we don’t know yet, since we are just now experiencing our 2020 wildfire season with this new emerging infectious disease,” said Erin Landguth, an associate professor at the Center for Population Health Research at the University of Montana. “However, we have a lot of pieces to this puzzle that warrant concern.”

Solid answers about the connection between air pollution and COVID-19 are probably two years away, said C. Arden Pope, a researcher at Brigham Young University who pioneered air pollution epidemiology.

But, he added, “It would not surprise me if air pollution contributes to the risk of coronavirus infection.”

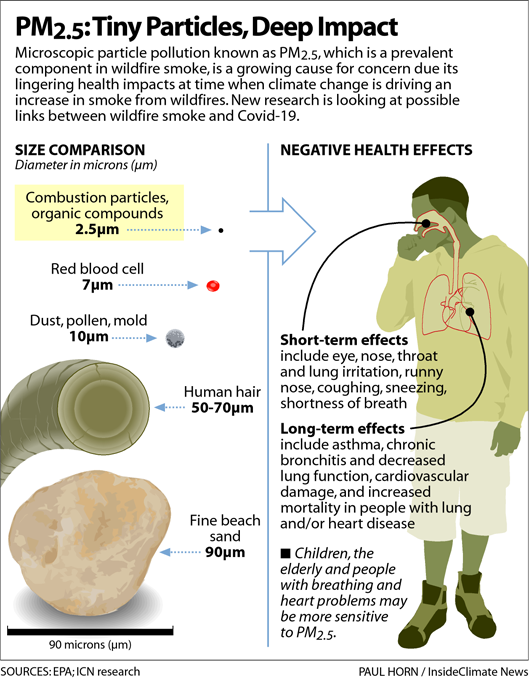

Pope’s own research, reported two years ago in the American Journal of Respiratory Critical Care Medicine, has linked PM2.5 air pollution — particulate matter that is smaller than 2.5 microns, or about 30 times smaller than a human hair — to the influenza virus.

And even though that link has been well-established in research, the most prominent study so far linking air pollution with the coronavirus has taken heat, Pope noted. The T.H. Chan School of Public Health at Harvard University last spring projected an 8% increase in mortality for increased pollution concentrations as small as 1 microgram of PM2.5 per cubic meter of air.

Since then, other studies have linked higher air pollution exposures to increased severity of COVID-19 infections. But so far, no research specifically ties wildfire smoke exposure to increased infection from the coronavirus or severity of symptoms, scientists told InsideClimate News.

Air Pollution, Regardless of its Source, Harms Health

How PM 2.5 makes people sick has been the subject of thousands of studies over decades. These microscopic particles of soot, which come from fossil fuel combustion as well as from burning forests and grasslands, burrow into the sensitive lining of the lungs, triggering heart and lung damage. They also are sometimes small enough to pass into the bloodstream.

The World Health Organization blames indoor pollution from burning wood and other fuels used for cooking and heating for 4 million premature deaths a year — just as many as from outdoor pollution sources.

Landguth pointed out that groups considered “sensitive” to air pollution make up about 30 percent of the U.S. population. Children under 18, adults over 65, women who are pregnant and those with medical conditions such as heart or lung disease, COPD, asthma, diabetes or compromised immune systems are included in that group. So are those who work outdoors or who have lower socioeconomic status, such as people who are homeless and those with limited access to medical care.

A subset of studies has begun drilling down into the health impacts of pollution from wildfires. One was led by Landguth, who reviewed a decade’s worth of data on PM 2.5 from wildfires in Montana and hospitalizations and urgent-care clinic visits for influenza.

Past studies of wildfire smoke have focused on acute cardiopulmonary health effects that happen within days or weeks of exposure. Landguth said that’s the timeframe the researchers expected to see increased treatment for flu in this study. Her team, however, was shocked to find delayed effects, as well.

After bad summer fire seasons, influenza was three to five times worse during the traditional flu season of fall and winter. After four bad fire years, including 2017, the number of annual flu cases in Montana jumped from the typical 3,000 to around 12,000.

“We were just — we couldn’t believe it,” she said, noting that the lag time was months, rather than days or weeks.

“We’re furiously pulling in that data right now trying to see if this association is gonna hold across other states [because] wildfire season is a lot longer in California, and it’s different in Oregon and Washington and Colorado,” she said. “We don’t know. We need to investigate that.”

Even though there hasn’t been enough time to compile the peer-reviewed research that doctors and public health professionals rely on, the coronavirus-wildfire smoke connections are already seen as significant. The federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention updated its coronavirus website this summer to say that people with COVID-19 are at increased risk from wildfire smoke, Landguth pointed out.

“Wildfire smoke can irritate your lungs, cause inflammation, affect your immune system and make you more prone to lung infections, including SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19,” the CDC page says. “Know how wildfire smoke can affect you and your loved ones during the COVID-19 pandemic and what you can do to protect yourselves.”