Here’s How That Annoying Fly Dodges Your Swatter

If an outdoors, socially-distanced gathering is part of your Thanksgiving plans, beware of uninvited guests. I don’t mean friendly neighbors who might invite themselves to a piece of pie.

I’m talking about flies. Buzzing around curiously, they’ll help themselves to whatever food you leave unattended. As they walk all around they could spread hundreds of types of bacteria they carry on their legs.

So you try sneaking up on one and it skedaddles. Why, oh why, is it so hard to swat a fly?

Flies are formidable opponents, with an arsenal of tools they carry all over their bodies.

For starters, their hair and antennae help a fly sense us as we walk up to them.

“They have sensory hairs all over their body that help them detect air currents,” said entomologist Jessica Fox, who studies flies’ shenanigans at Case Western Reserve University in Ohio.

Not only can they feel us, they can see us too.

“They have a very small blind spot in the back of their head,” Fox said, “but a lot of flies can see almost 360 degrees around their heads.”

And a fly’s eyes and tiny brain process information 10 times faster than human eyes and brains.

“Compared to flies, humans are slow and sluggish creatures,” said Sanjay Sane, who researches flies at the National Centre for Biological Sciences at the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research in Bangalore, India.

Once the fly escapes your swatter and is in the air, it’s in its element and your job is even tougher. Seen up close and slowed down, a fly’s aerobatics are impressive: It makes razor-sharp turns with ease and at great speed.

What makes this possible is a pair of modified wings called halteres, a Greek word for dumbbell, which describes their shape. All of the 200,000 species of flies that scientists have described have a pair of halteres and a pair of wings. (That includes mosquitoes, which, wouldn’t you know it, are flies too.) Most other insects — bees, butterflies, dragonflies — have four wings and no halteres.

As a fly turns, its halteres sense the rotation. In a split second, neurons at the base of the halteres send information to the fly’s muscles to steer its wings and keep its head steady.

“Houseflies flap their wings about 200 times per second, which means they really only have five milliseconds to figure out what the next wingbeat is going to be like. And if you’re using vision that takes too long to do,” Fox said. “They really need a mechanical receptor in order to be able to sense their body rotations and correct them on the timescale that they need.”

Though flies are a pesky pest and we are constantly in their pursuit, they likely evolved halteres to escape other animals besides us.

“Flies hang out on the backs of cows,” said Sane. “The tail of a cow trying to flick insects off, it’s likely to kill the fly if it doesn’t fly off fast.” Lizard tongues are also quick-moving threats.

And then there’s flies themselves. In lightning-fast chases, males compete for the ability to mate.

“These chases are among the most aerobatic chases that I’ve ever seen; there’s nothing that comes even close,” said Sane. “And if flies did not turn very fast they’ll get caught and slammed to the ground.”

When researchers remove a fly’s halteres, it can no longer control its flight. It loses all sense of where its body is in space. In slowed-down videos, flies without halteres give the impression of being drunk.

“They don’t seem to know; they just keep flapping,” said Fox. “They just keep pitching and rolling and eventually they fall. We’ve got a lot of great videos of these flies comedically falling out of the sky.” (You can see more examples in the Deep Look video embedded in this story.)

If a fly gets inside your house, its halteres will help it do a fly’s signature move: the ceiling landing.

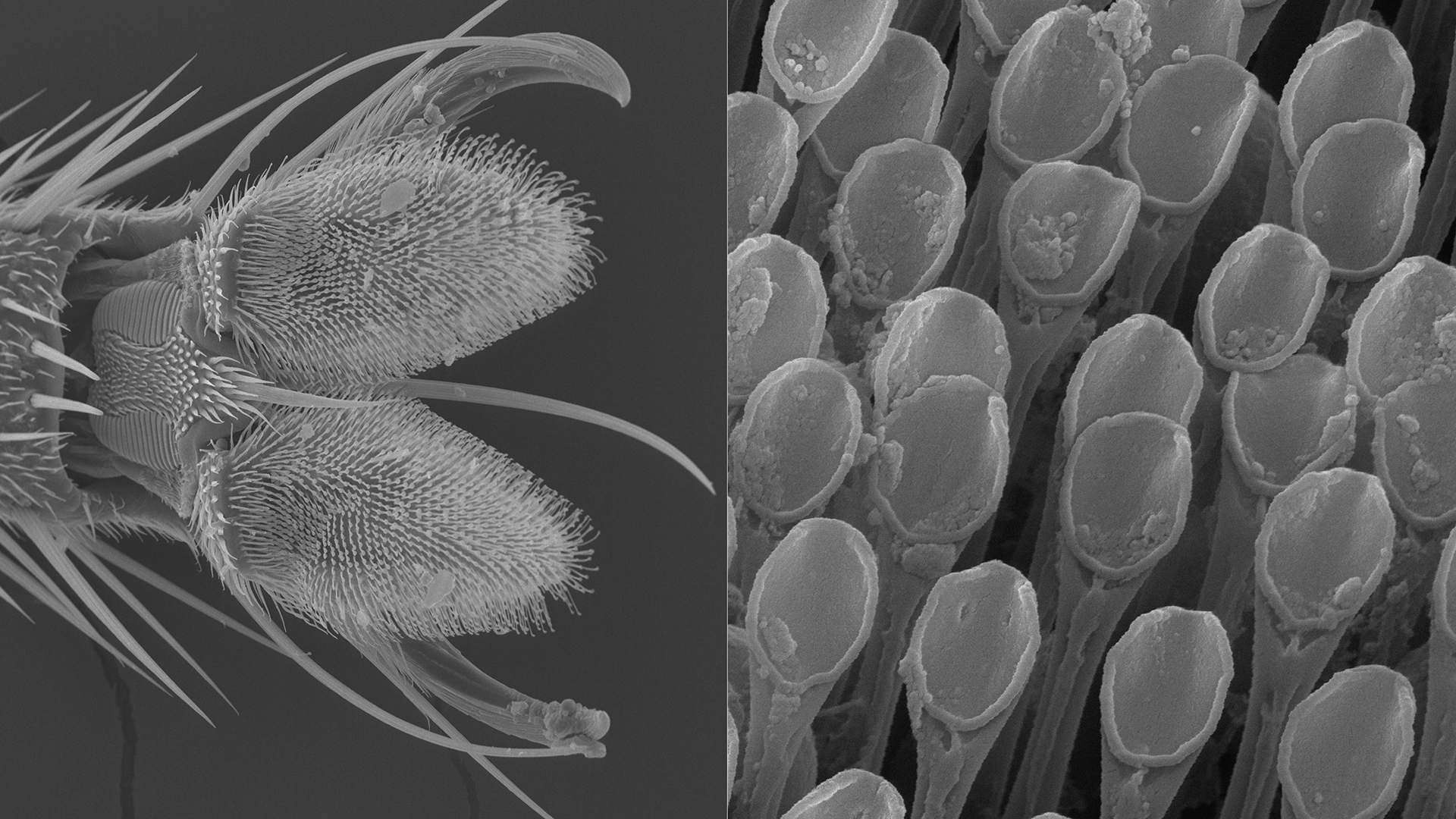

It hangs there with tiny hooks and sticky pads on its feet. The pads, called pulvilli, have microscopic hairs that excrete a liquid that sticks to the surface under pressure, sort of like suction. Hooks on the fly’s feet also help it stay put, by attaching to microscopic imperfections on the surface of the ceiling.

Despite the fly’s slick tools, Sane recommends one trick next time you try to nab one.

“Flies process information about moving objects but they cannot process static objects,” he explained. “Thus, the best way to approach a fly is in small, quasi-static steps such that they do not see you as a moving object.”

If you go very slowly, and then pounce, you might stand a chance.

“Good luck, though,” he said, “because flies are spectacularly fast.”