“Pfizer did offer an additional allotment coming out of that plan — basically the second quarter allotment — multiple times,” Gottlieb told CNBC.

Gottlieb noted that the government has agreements to buy hundreds of millions of doses of vaccines from six manufacturers as part of Operation Warp Speed, the Trump administration’s more than $10 billion push to make a coronavirus vaccine available in record time. He suspects the government is betting more than one vaccine would ultimately get the FDA’s authorization.

“That perhaps could be why they didn’t take up that additional 100 million option agreement, which really wouldn’t have required necessarily them to front money. It was just an agreement that they would purchase those vaccines,” Gottlieb said. “So Pfizer has gone ahead and entered into some agreements with other countries to sell them some of that vaccine in the second quarter of 2021.”

And that could mean there’s less available for the U.S. government to buy when it’s ready to do so.

The New York Times first reported Monday on the negotiations for more doses, saying that Pfizer offered the U.S. government between 100 million and 500 million additional doses and warned that its vaccine could be in short supply, given demand around the world. As a result, a second allotment might not be available to the U.S. until next June.

A senior administration official told reporters during a briefing Monday that the Times reporting wasn’t accurate: “We’re in the middle of a negotiation right now and we can’t talk publicly about it, but we feel absolutely confident we will get the vaccine doses for which we’ve contracted and will have a sufficient number of doses to vaccinate all Americans who desire one before the end of second quarter 2021.”

A spokesperson for HHS echoed that explanation in a series of tweets on Tuesday, saying, “At no time did OWS turn down an offer from Pfizer for any number of millions of doses having a firm delivery date and quantity, and it’s a shame that someone is misinforming the American public.”

Pfizer didn’t respond to NPR’s request for comment on this story.

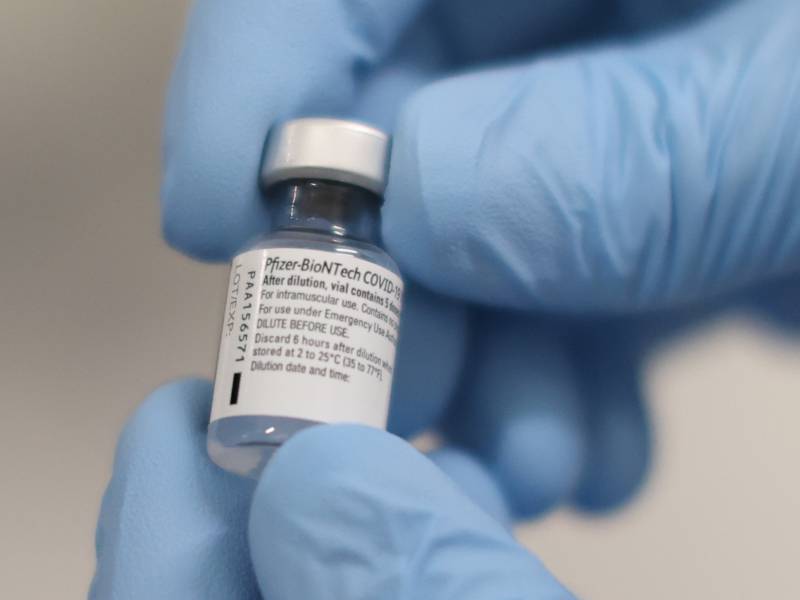

In July, Pfizer signed a $1.95 billion agreement with Operation Warp Speed. As part of the deal, the government agreed to purchase 100 million doses of Pfizer’s vaccine, but the transaction would occur only if the vaccine Pfizer is developing in partnership with BioNTech, a German company, received the FDA’s OK.

It’s not unusual for a company under contract with the government to suggest a modification, such as more doses in the first allotment, said Franklin Turner, a partner at McCarter & English who specializes in government contracting. But there can be any number of reasons the government might decline.

“If I had a dime for every time the government took a step or a position that seems counterintuitive and quite frankly, mind-boggling, I’d be a very rich human being at this point in my life,” Franklin said.

On Thursday, the advisory panel voted 17-4, with one abstention, to recommend that the COVID-19 vaccine being developed by Pfizer and BioNTech be authorized for emergency use.

It’s possible the government could have gotten better follow-on delivery contract terms to begin with, said James Love, director of Knowledge Ecology International. Though he noted that the intellectual property rights in the contract aren’t particularly favorable to the federal government either, as NPR has reported. “At some point, not placing orders when the whole world is placing orders, was a mistake,” Love said.

If the U.S. did miss out on more doses because it declined them, it would be “a spectacular failure,” said Rena Conti, a health economist at Boston University.

“Contracts are forward-looking, that means we could have (and did) sign contracts with other manufacturers that reserve future capacity when it became available,” she said. “We should have [been] including language in every contract reserving the rights to more quantity in advance at a given price.”

Although the Pfizer contract includes the option to buy an additional 500 million doses of its vaccine, that transaction would require a separate agreement, and the price would be subject to change, the contract says.

“Having more quantity reserved is smart economics given the uncertainty entailed in which vaccine comes to market in a given time period, and which vaccine will be most safe, [effective] and able to manufacture at scale,” Conti said. “There is no downside cost or risk to having these forward contracts and there is plenty to gain for the American public.”

9(MDAxOTAwOTE4MDEyMTkxMDAzNjczZDljZA004))