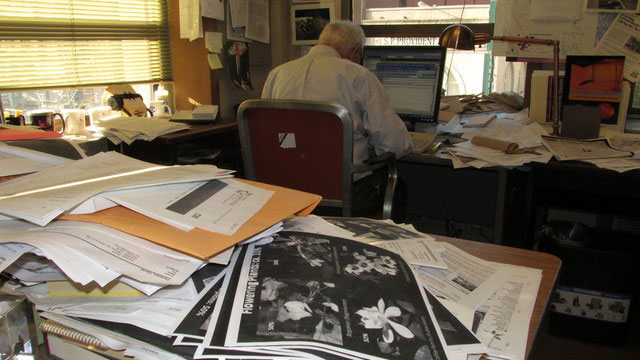

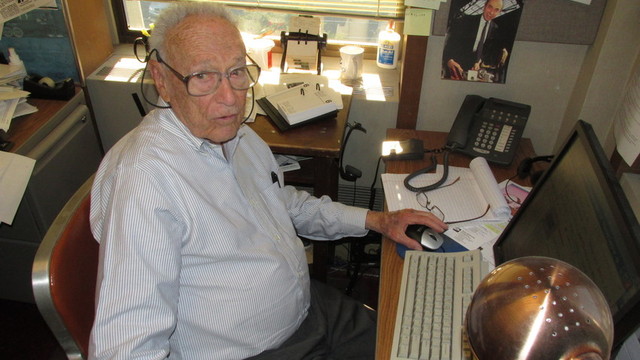

David Perlman was the kind of journalist who had newspaper ink in his veins. When he retired from the San Francisco Chronicle three years ago, at 98, he was the oldest known full-time news reporter at a U.S. metro newspaper.

With a career that spanned most of the last century and the start of this one, he covered the most significant scientific advancements of our time.

This year we lost him. He passed away in June, at age 101.

But the legendary newsman is still winning awards. This month Perlman received the posthumous Mark Twain Award for Journalistic Excellence from the California Press Foundation.

“Dave was a newspaper man and so was Mark Twain,” said longtime colleague and fellow science writer Charlie Petit, presenting the award to Perlman’s family. “They were both great admirers of plain talk.”

But, Petit said, they differed in one key respect: “Dave stuck like a barnacle to reporting, while Twain was all over the place.”

Born in 1918, David Perlman spent most of his childhood in New York City and Paris. He received a master’s degree in journalism from Columbia University in 1940. After a quick stint at a paper in North Dakota, he got a job as a copy boy at the Chronicle and was soon writing police stories. In 1941 he married poet and writer Anne Salz, whom he met at a party on Lombard Street.

After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Perlman enlisted in the U.S. Army. When the war ended, he worked for a time as a foreign correspondent in Paris for the New York Herald Tribune. In 1951, he and Anne moved back to San Francisco and he rejoined the Chronicle as a reporter, where he remained for the rest of his career.

Some reporters grow disenchanted with journalism after years of deadline pressure, pressure from management and rounds of buyouts and layoffs. Perlman always encouraged others to join him in the field.

“Don’t give up on journalism,” he said in a 2014 interview with KQED. “It’s a great trade, a great profession. And really you’re doing good. You’re helping to inform the public about whatever issue. Yeah, I love being a reporter, and I think anybody who enters journalism is going to have a good time and make a modest living.”

Perlman’s reporting style was speedy, eloquent, illuminating and clear.

“He could take the most complicated story and just make it accessible to all readers,” said Terry Robertson, Perlman’s last editor at the Chronicle, working with him for 12 years. Robinson is now retired and living in Washington state.

“But at the same time, he was very meticulous and I learned very early, don’t mess with his precision to make something a little snappier! He just wrote with a passion.”

A total eclipse of the sun will turn day into night across a narrow swath of the U.S. this month when the full moon moves to block the sun’s face and create a coast-to-coast phenomenon that hasn’t occurred in nearly 130 years […] The summer air will turn chilly, birds will chirp uneasily in the unexpected darkness and the stars will emerge.

Perlman’s final story for the Chronicle before retiring is dated Aug. 5 2017.

“And he wrote [the story] as brilliantly and as flawlessly, as any of the other eclipses that he wrote about,” said Steve Rubenstein, a colleague and friend at the Chronicle, who visited Perlman at home after his retirement.

“Solar eclipses are fairly rare, but not as rare as he was.”

Even before Rubenstein first walked into the Chronicle newsroom in 1976, he admired Dave Perlman.

“Then I was 20-something. And Dave was already a legend. It was just an honor to sit in the same room with him. And then to find myself, the next morning, my story wrapped up in the same Chronicle with the same rubber band that his story was wrapped up with.”

On Perlman’s retirement, Rubenstein became the longest-working staff member at the Chronicle. He also inherited some Perlman treasures: his press credential from covering the 1969 Apollo 11 moonwalk in Houston, the manual Olivetti typewriter where Perlman pounded out stories with two fingers, and the telegram sent via Western Union, which was how Perlman sent his moonwalk story to the Chronicle.

“These are sort of as close as you get to the Dead Sea Scrolls as there are in our business,” Rubenstein said.

The last time I spoke to Perlman was summer 2019, for the 50th anniversary of the moonwalk. I was astonished at the clarity of his memories.

“I remember there was a moment of silence when the two guys climbed out of the spacecraft and actually set foot on the moon,” he told me. “And we typed our stories as fast as we could.”

Perlman was covering one of the most significant moments of mankind’s history, but he was focused on his job, not the poetry of the moment.

“I was covering a damn story! The important thing was to beat a deadline.”

When I asked him about his most meaningful stories, Perlman said he loved to be in the field with scientists when discoveries were happening.

In the 60s, Perlman joined a monthslong expedition to the Galapagos Islands, retracing Charles Darwin’s research on evolution, filing dozens of stories via the ship’s radio. Stories about evolution and human origins became among his favorite subjects.

“He was there to see things actually that we are seeing for the first time,” said UC Berkeley paleoanthropologist Timothy White.

“And that was one of the gifts that he wanted to give to his readers to be able to recount those kinds of experiences.”

In December 2005, Perlman joined White on an expedition in Ethiopia studying pre-human fossil remains and tools.

“And in this case,” recalled Perlman in 2019, “I remember Tim White lifting up a rock and to me it was just a rock. But sure enough, it was an ax — face of an ax. And that stone had been laying there for millions of years. And that was quite a thrill to be able to handle it.”

Perlman arrived at science writing literally by accident. It was around 1957…

“I happened to break my leg skiing and was reading a book. I can even name the book: ‘The Nature of the Universe’ by a British astronomer named Fred Hoyle.”

He was expecting to be bored, but found himself absorbed.

“And I got kind of curious to know whatever astronomers do. What’s all that about?”

So Perlman arranged a visit to Lick Observatory, atop Mount Hamilton, outside of San Jose. And there he met astronomer George Herbig, a University of Hawaii astronomer who died in 2013.

“And I sort of asked him, in a way,” recalled Perlman, “what do you do for a living? And he said, ‘I’m interested in stars that are being born in the Orion Nebula.’ And I thought, you know, the idea of stars being born, that’s a crazy idea.”

After that story, Perlman went back to the Chronicle and became a science reporter.

Even as a boy, he loved the news business. At the age of about 12 he saw the play “The Front Page.”

Perlman could recite from memory the play’s opening description of reporters, as “Seedy, catatonic Paul Reveres, full of strange oaths and a touch of childhood.”

“I wanted to be like that. And as a matter of fact, I got to be like that,” Perlman said. “I think I got more than a touch of childhood.”

His example continues to inspire both new and old reporters today. Each year the American Geophysical Union, a large scientific community, gives out the David Perlman Award, for science reporting on deadline. The recipient this year, Ann Gibbons, writer at the publication Science, remembers hearing Perlman speak about working as a science writer, while she was an undergraduate at Berkeley.

She said he was one of the first people who showed her a path that could combine her love of science and writing, and to make a living at it.

No one, however, will remember David Perlman as seedy or catatonic. They will remember him as a straight-talking truth teller.

David Perlman’s author page at the San Francisco Chronicle remains live.

Craig Miller contributed reporting to this piece.