“Firefighters are savvy to this and sometimes even ahead of the science, just through their anecdotal experience,” Lareau said. “They know that to watch out for that kind of situation because it can lead to all these potentially erratic and extreme fire behaviors.”

Scientists are learning too, sending weather balloons up into these giant clouds. The equipment is often never seen again, after sending readings to researchers on the ground. They also fly research aircrafts straight through the dark, gray columns. One research group flew NASA’s DC-8 over a wildfire in western Washington in 2019. The specialized radar, lidar, and sensors on the flying laboratories revealed an extreme environment: winds inside the fire clouds blowing as strong as 130 miles per hour, rivaling the strongest thunderstorms on Earth.

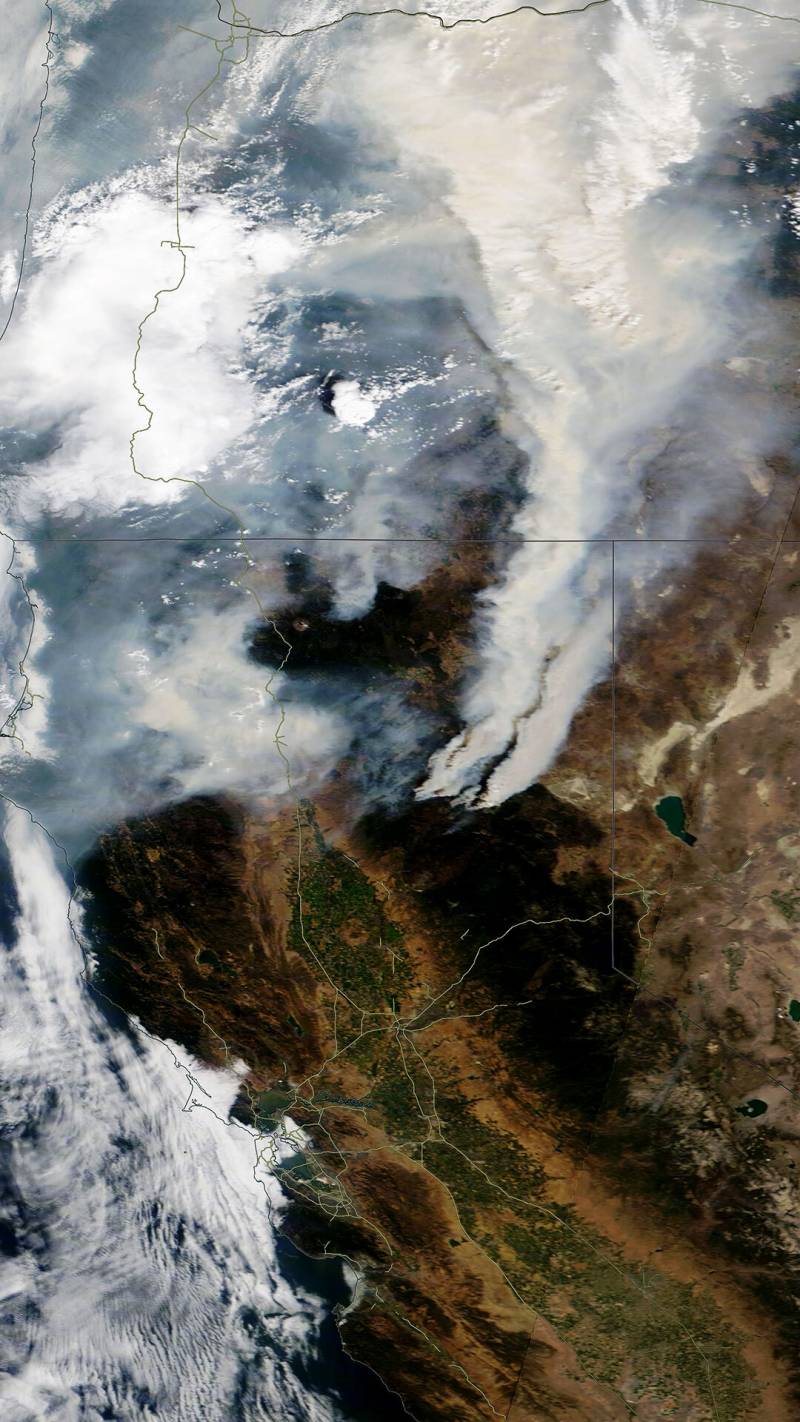

“Once fires get to the point where they’re producing their own weather, that’s when we get all these feedbacks and a vicious cycle between what the fire is doing and what it’s forcing the atmosphere to do. And then what the atmosphere is making the fire do. That can lead to these kind of explosive growth phases in the fire,” Lareau said.

‘We’re Witnessing Emergent Trends Right Now’

Warming temperatures are roasting forests, drying out soil and vegetation and priming them to burn. If climate change means the future will have more fire, Lareau says there will be more pyro clouds rising above California fires.

“We’re witnessing emergent trends right now, in fire severity, fire size, in these extremes of fire weather,” he said. “My basic prediction would just be more, more of that in the years to come.”

Peterson, the Navy researcher, studies the impact of pyrocumulonimbus clouds on the global atmospheric composition.

“There will be a smoke plume left over, usually up at the level of the jetstream winds. When you push smoke up high, it can be transported long distances rapidly,” he said. “Sometimes these fires are so intense that they penetrate into the next level of the atmosphere above the weather, the stratosphere. An aerosol plume at that level tends to stay there.

“Over the past four, five years, we have definitely seen some of the largest known pyroCb outbreaks across the globe,” Peterson said.

The task now is to predict them better, especially the atmospheric conditions that create that characteristic uplift around a fire. Scientists are also trying to model and forecast the movements of aerosol particles around the globe.

“What we do know is that these plumes can rival volcanic plumes in terms of their size and magnitude. But the chemistry is different — it’s smoke, not volcanic material,” he said. “Just imagine this blob of smoke sitting at like 60,000 feet. The smoke is an aerosol particle that will absorb solar radiation and heat the layer that it’s in, which can affect the stratospheric weather.”