Decades and even centuries of fire suppression — the long-held policy of the U.S. Forest Service and other agencies — also fed the wildfires. Many habitats across the Western U.S. evolved to experience frequent burns, which cleared away excess fuel, and Indigenous communities often used fire to keep those habitats open as well. Now forests are packed with many more trees.

The combination has led to wildfires that burn 10 times the acreage as 50 years ago. Massive, destructive burn years like 2020 are projected to become much more common as climate change marches forward, though aggressive forest management could blunt some of the worst outcomes, research shows. And wildfires are not just tied to the West. This year, wildfires burned from Canada’s East to West coasts and deep into Louisiana.

Christopher Migliaccio, an immunologist at the University of Montana, studies the impact of wildfire smoke on human health. When he moved to Montana in 2000, wildfires weren’t top-of-mind for most people. But within the past decade, “the concern has gotten huge,” he says. “And it’s gone global.”

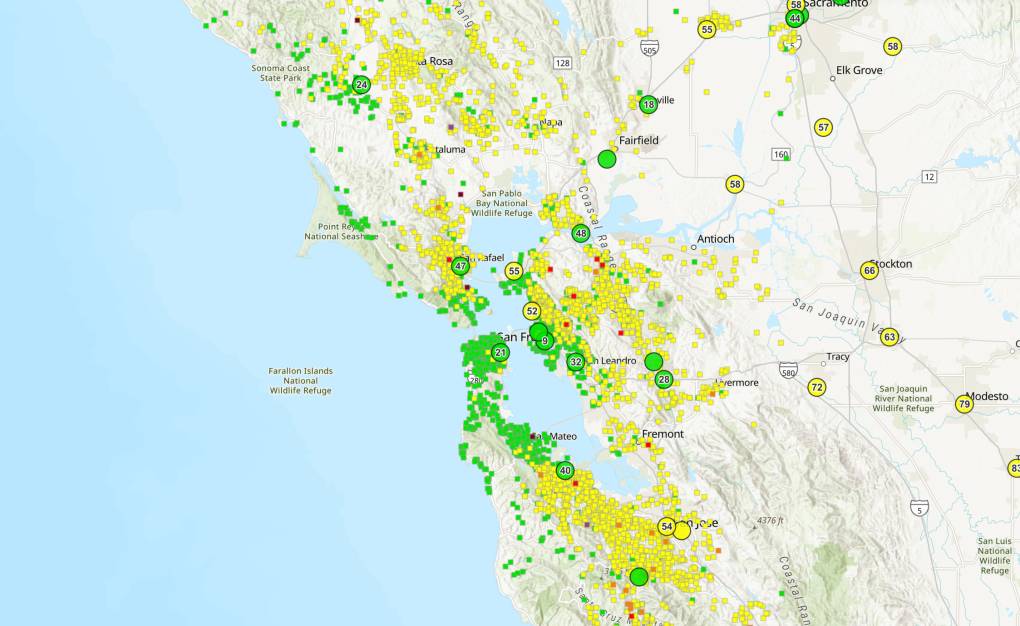

That’s because the health impacts leak well outside the immediate realm of the fires. Smoke, and all its fine particles, can travel thousands of miles. “When you see a wildfire smoke plume, you see that pollution. Essentially, the smoke that you’re seeing is PM2.5,” says Colleen Reid, an environmental public health expert at the University of Colorado, Boulder.

It’s not yet completely clear if wildfire smoke particles induce different health outcomes than PM2.5 from other sources, like roadways, though some research points that direction. But the tiny particles from fires and other pollution sources are so small they cross from lungs into the bloodstream, driving inflammation throughout the body. Even short-term exposure to wildfire smoke makes lung problems like asthma worse, as well as a panoply of other health issues, from heart attacks to neurological issues.

Migliaccio led a study that followed Montanans exposed to extremely high doses of smoke for 49 straight days in 2017. It found their lung function was depressed for at least two years afterward.

In 41 states, air quality had been getting better between 2000 and the 2010s. But as wildfires exploded, those improvements stopped or even reversed. Smoke was responsible for just intermittent “exceedances,” when air pollution exceeds EPA’s limits, in the early part of the record. By 2020-2022, wildfire smoke was the primary cause of bad air in four western states and a major contributor in 17 others.

Solutions are not straightforward

Wildfires are a natural and necessary ecological reality in many parts of the country. But research predicts the frequency and size of fires will grow precipitously in coming decades, increasing peoples’ exposure to smoke.

The Clean Air Act effectively regulates point-source pollution, like soot from power plants. It is less effective at regulating risk from smoke, which drifts across state borders and affects people far from the wildfires themselves.

Dialing back the climate pressures that exacerbate wildfires is critical, says Childs. But so is creating forest and fire management policies that reduce exposure to very high concentrations of smoke. That could be, somewhat counterintuitively, increasing the number of prescribed fires, which can lessen the risk of catastrophic wildfires, though they also generate local smoke plumes.

In the meantime, people can take steps to protect themselves from inevitable smoke exposure, says Reid. Installing air filters in your home — and keeping them clean — can go a long way. Health experts recommend wearing N95 or KN95 masks if you have to go outdoors, and to avoid exercise in smoky air if possible.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

9(MDAxOTAwOTE4MDEyMTkxMDAzNjczZDljZA004))

9(MDAxOTAwOTE4MDEyMTkxMDAzNjczZDljZA004))