Five years after the Camp Fire, the deadliest fire in California’s recorded history, the state is still grappling with how to prevent wildfire destruction and live in harmony with natural fire.

New research published Friday from Stanford University and Columbia University points the way forward. In it, researchers quantify for the first time the magnitude of protection an area enjoys following a mild, beneficial fire — such as a prescribed fire — and how long that protection lasts.

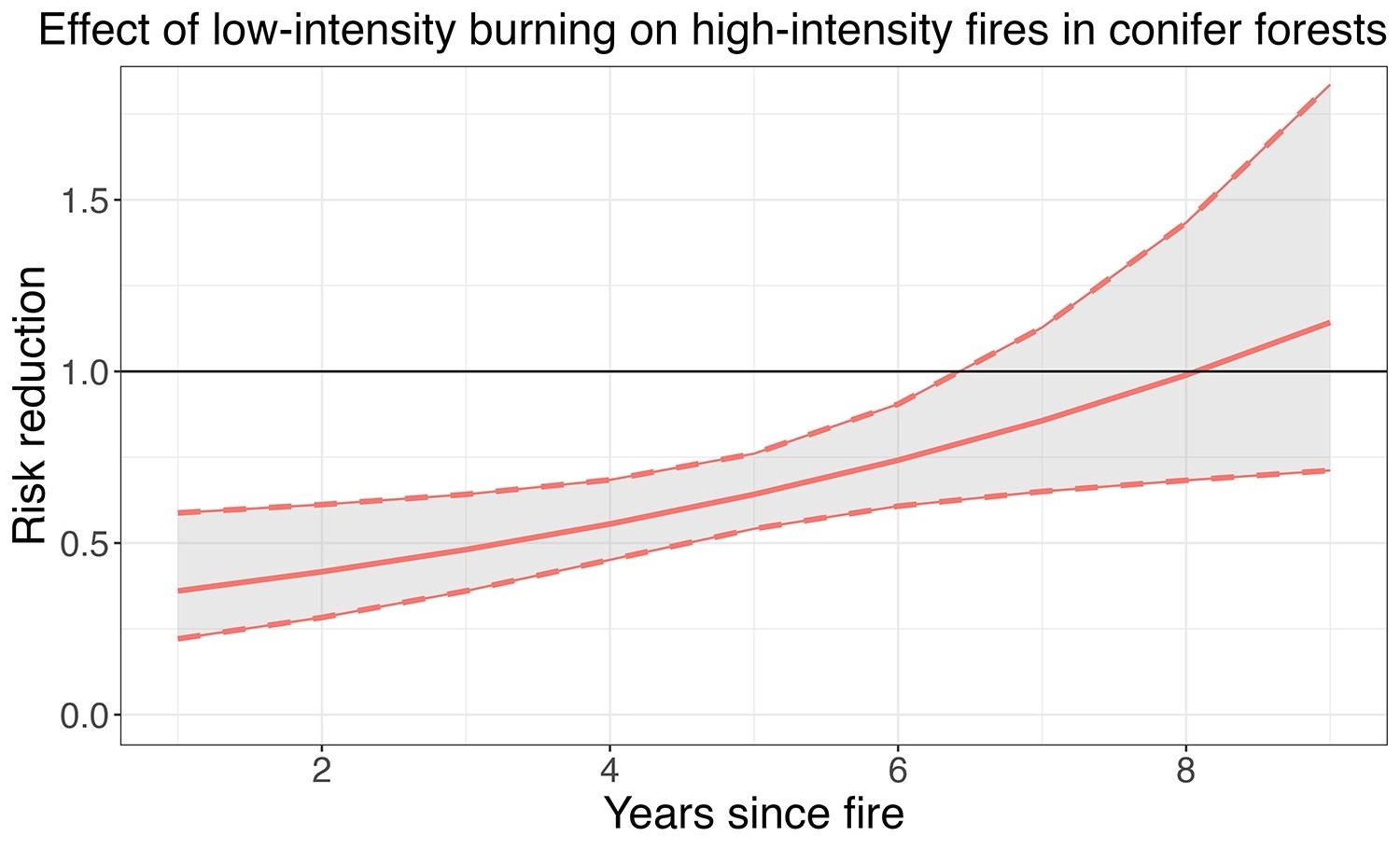

The authors find that after an area has experienced low-intensity fire, the likelihood of a future high-intensity fire — the kind that grows out of control and takes out neighborhoods — is reduced by 64%. The protection lasts at least six years and then diminishes after that.

“It totally substantiates what we already see on the ground and what we already know to be true, which is that low- to moderate-severity fire begets more of the same,” said Lenya Quinn-Davidson, the director of the UC Ag and Natural Resources Fire Network.