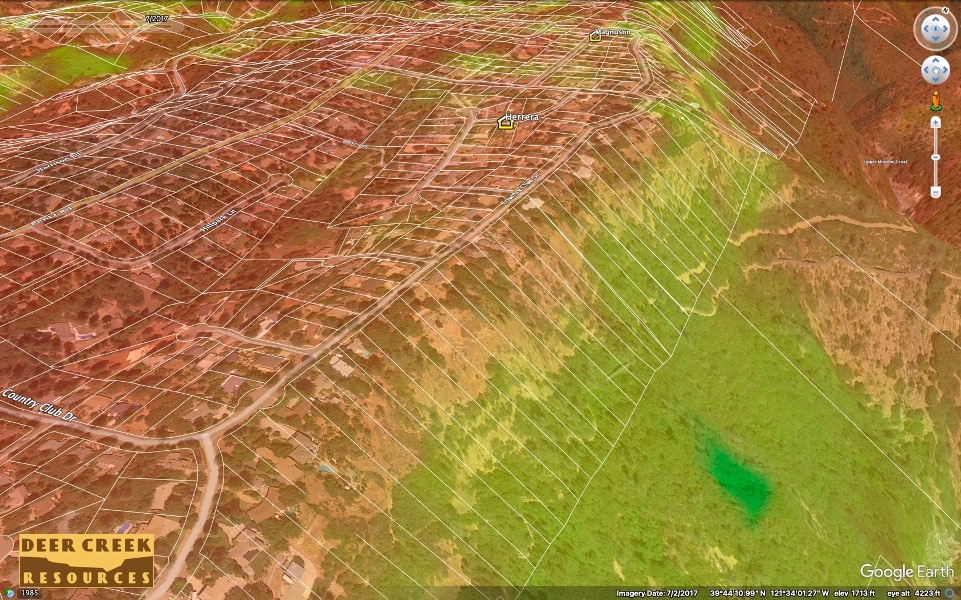

More examples around the state showed the extent of the problem: images from the area around Nevada City, Grass Valley and Marin County, followed by the Oakland hills, were all worryingly crowded with fire fuel and not designed to enable fuel treatment projects.

“It’s not physically possible, given the configuration of many of these places, to even do the work,” Lunder said.

Lunder said places should be redesigned with fire in mind if they are rebuilt. He pointed to the area burned by the Angora Fire near Fallen Leaf Lake, south of Tahoe, in 2007, where neighborhoods were built to align with the canyon. That meant the spine of the road system followed the winds flowing through the canyon. As a result, the Angora Fire hopscotched from house to house easily, leaving a trail of destruction.

“If we’ve been thinking about this before we built a subdivision, maybe we could have oriented the streets perpendicular to the prevailing wind,” he said. “But we don’t think about that, nowhere do we think about that when we build a subdivision.”

So, it’s been rebuilt with the same alignment and the same house-to-house potential for the next fire to take it out. Lunder called this type of community “fire antagonistic.”

“It’s not that [the neighborhoods] were developed without fire in mind, it’s that they’re actively in fire’s face. What are you going to do about that? We see how that’s working out,” he said.

Lunder acknowledged that there are huge hurdles. Counties need a tax base for this work to happen. They need the political will to make decisions like redesigning subdivisions and not allowing some redevelopment that is surely to be unpopular. He is also sensitive to the worry that lower-income residents can be displaced from communities in redevelopment. So, that needs to be considered too, he said.

“But we need to start thinking about this now,” Lunder said.

What causes megafires?

Extreme fires, sometimes called “megafires,” are at fault for a lot of the things we don’t like about fire. Burned neighborhoods. Lost lives. Charred landscapes where everything from the trees to the microbes in the soil are killed.

So it’s worth understanding how these fires — so intense they’re impervious to firefighters’ efforts — happen and what, if anything, can be done to prevent them. Extreme fires were the topic of a suite of talks held at the same conference.

In some respects, we know what drives them:

- Hotter, drier conditions exacerbated by climate change

- A longer fire season, also thanks to climate change

- More chaotic weather patterns can promote the development of pyroconvection (when a fire creates its own weather system) and prompt erratic and sudden fire behaviors, overwhelming firefighters’ efforts

- The history of fire suppression, tree plantations and invasive species

But there are still big gaps in knowledge and no surefire indicators pointing to why some fires merely become big while others go on to become extreme. Some surprising research indicates that extreme fires have flourished under milder weather conditions compared to big fires that behaved more normally.

How dry the previous two weeks had been, in these cases, seemed to play a role in influencing fire behavior.

Andrea Duane, a wildfire science researcher at UC Davis, concluded her talk with a sobering reminder that climate projections point toward worse fires in the future, so getting a better handle on extreme fires could not be more timely.

Empowering more indigenous fire

Attendees of the conference said that if there is cause for future hope, it is the voices of native and Indigenous people who are gaining broader influence over California’s fire policy for their intimate knowledge of how to use fire to care for landscapes and people.

A session about nurturing indigenous fire stewardship was at capacity, with people sitting on the floor and overflowing into the hall. A few years ago, at these kinds of fire conferences, several speakers mentioned that wouldn’t have been the case.