Solutions: School districts can rebuild schools at elevations above flood zones or move them entirely away from risky areas. But there’s an equity issue for school districts that may want to address the rising sea level independently.

Districts in less economically privileged communities may not have the funds or ability to move a school and must rely on community or region-wide efforts — sea walls, levees, or out-of-the-box solutions — to protect schools. That means city, county, and state leaders must come alongside communities to develop plans for a wetter future.

What’s new: While seawalls and levees are the usual options to protect communities from floodwaters, they come with a sizable price tag. Plus, sea-level rise scientists behind a new paper published in Scientific Reports suggest that sea walls or other shoreline barriers “can backfire,” leading to more groundwater flooding inland, said Xin Su, a research assistant professor at the University of Memphis. As a result, the researchers suggest any solution with a barrier in mind needs a secondary plan — like pumps — to deal with the extra water inland.

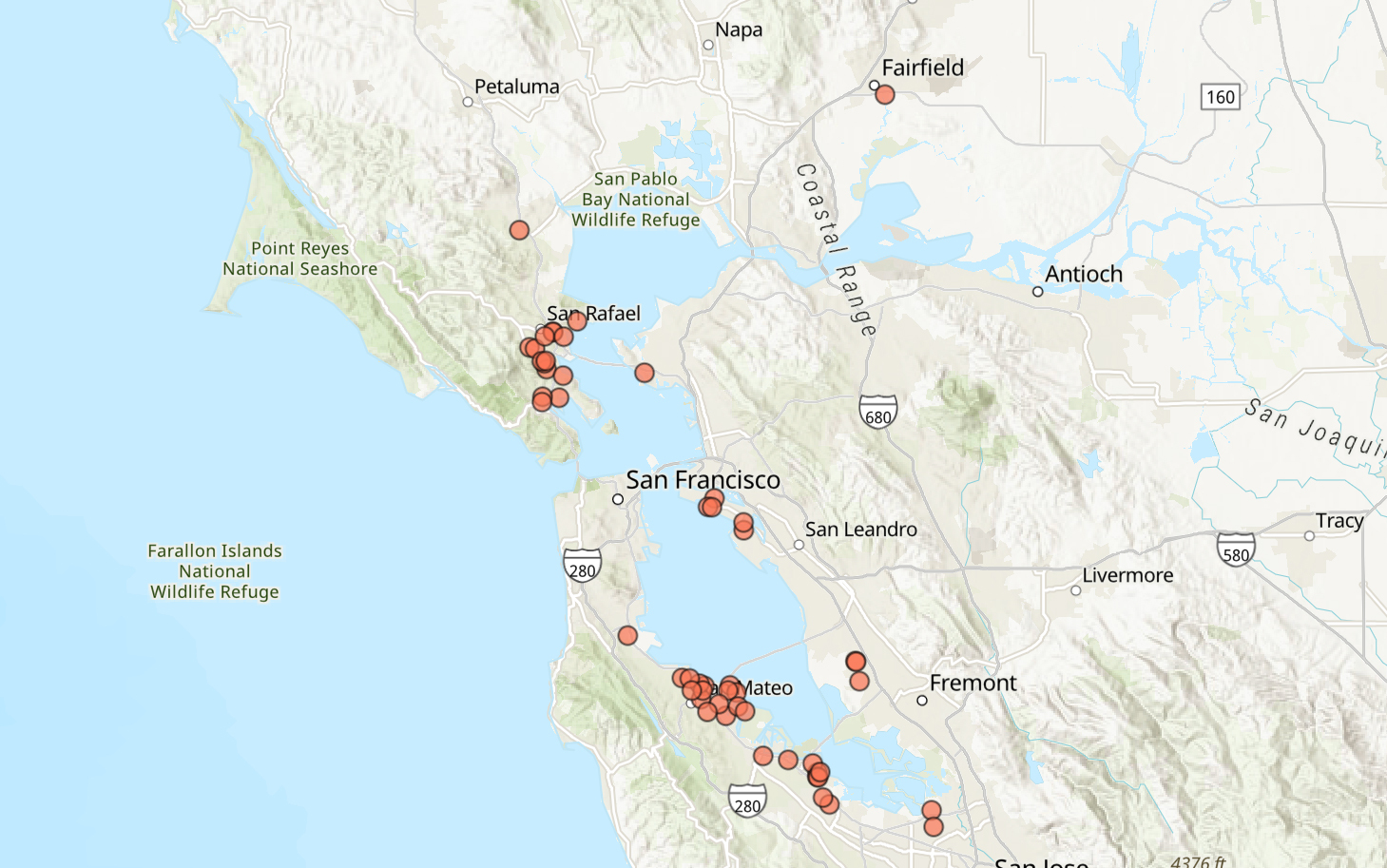

The bottom line: The Bay Area needs to develop large-scale sea-level rise solutions — for schools, highways, homes, major infrastructure, etc. — in the coming decades as the pace of flooding increases. It will cost as much as $110 billion to protect the entire bay shore from nearly a foot and a half of sea-level rise and a 100-year storm, according to a funding report from last summer by various Bay Area governments. Failing to do so could push the cost of preparing the region for rising tides to over $230 billion, the authors note. The good news is that the Bay Area Conservation and Development Commission is working on a regional sea-level rise plan with a draft due at the end of the year.