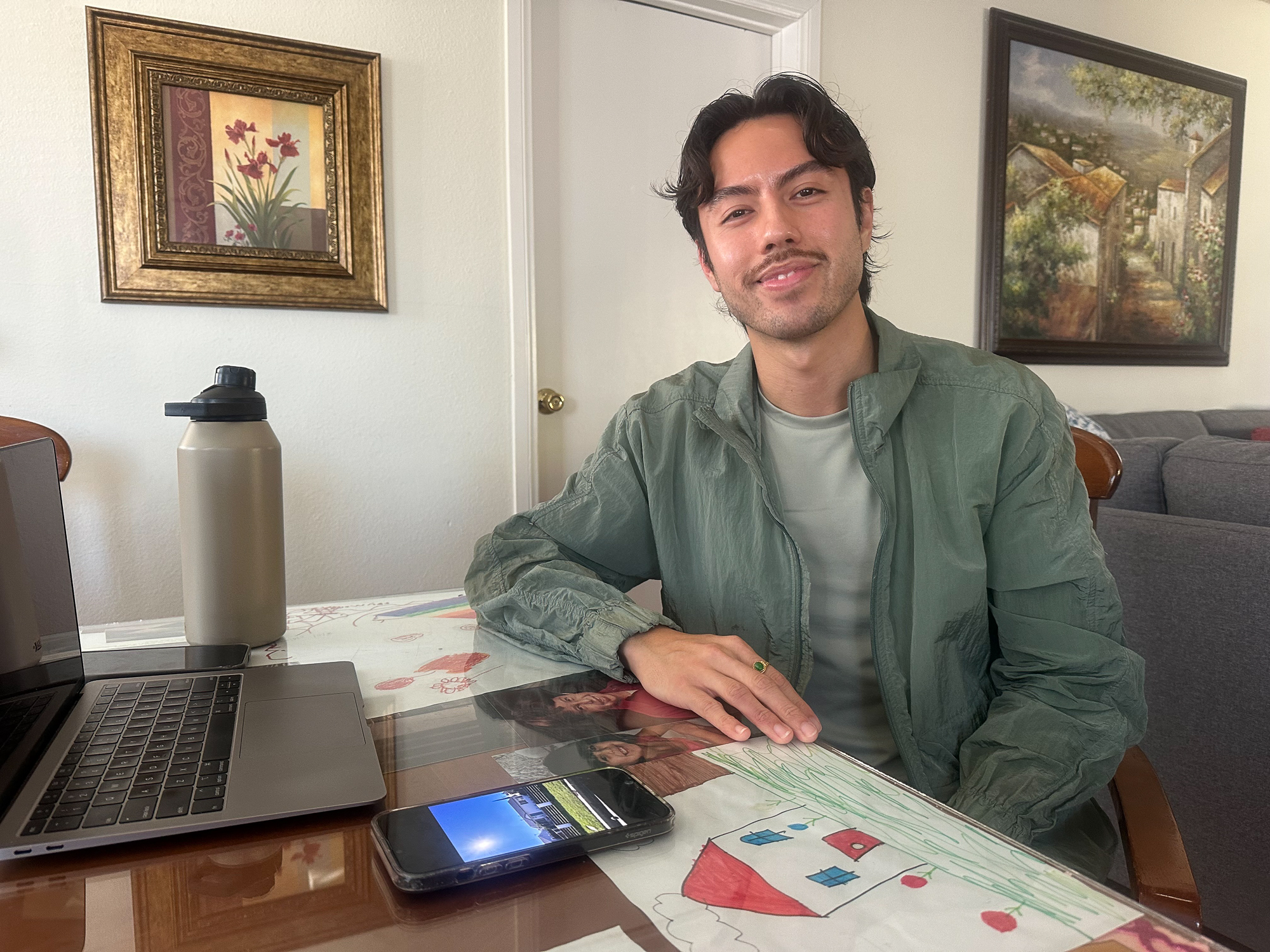

Ray López-Chang stays with his grandma in the El Sereno neighborhood of Los Angeles, south of Pasadena, for now. The tall, bubbly 30-year-old with glowing skin hushed his dog, Cielo, from barking when we met at this temporary home: a one-story house on a hill. He lived here off and on when he was younger.

López-Chang evacuated his family from their home in Altadena at 3 a.m. on Jan. 8. The Eaton Fire roared, forcing evacuations across the town. Six hours later, he briefly returned to grab clothes, medications and valuables they didn’t want to lose.

“It felt very chaotic and perilous inside with cars snaking through small streets, folks running through sidewalks,” he said.

They also spent precious time spraying down their house with water in hopes of preventing wind-whipped embers from igniting the house. Before they left, López-Chang said his mom grabbed a figurine of a Catholic saint. But then placed the icon back “to protect the home,” López-Chang said.

Salomón Huerta rents a small home in Altadena several blocks away. The figurative painter was on his way home from work when his wife called nervously as the fire approached. “She goes: ‘You better hurry up because I can see the fire,’” he said.

The fires burning in Southern California have consumed more than 40,000 acres and more than 10,700 structures, as well as the lives of 25 people, at least. The Eaton Fire ripped through Altadena and is still not contained.

López-Chang and Huerta are two of the thousands of residents within that evacuation zone who cannot return, many who have yet to find out if their homes are still standing. KQED sent me to report on the fires, and friends connected me to them. The families tried to reach their homes multiple times after the wind and flames moderated, but the National Guard turned them around.

Cal Fire and Los Angeles County created a website where families can check on the status of their homes. When I checked, López-Chang’s home was not yet listed. On my next trip to the fire zone, I drove by to see for myself.

Turn off the 210 Freeway onto Lincoln Avenue and move toward the San Gabriel Mountains, and all along the road, you’ll find shops and groups of people collecting donations — boxes of clothes, stacks of bottled water and mountains of food — for fire victims, many of whom were still waiting to see what remains, if anything, of their homes.