Finding Faults: Scientists Close in on Napa Quake Origins

Finding Faults: Scientists Close in on Napa Quake Origins

It took less than 20 seconds to shake apart historic buildings and topple chimneys from Vallejo to St. Helena.

But throughout the Napa Valley, the August 24th South Napa Earthquake left its calling cards — not just the startling damage in downtown Napa but subtle traces on the ground itself: clues to what actually happened deep below the surface. In fact, geologists now say that the South Napa quake created more surface fractures than any known quake of its size in California.

Weeks after the magnitude-6.0 shaker, a new picture is emerging of the complex geology underneath. The quake is literally re-drawing the fault maps and providing valuable clues to the next major seismic event.

“It’s an incredible laboratory,” says geologist David Schwartz, scrutinizing some buckled pavement in a driveway along Dry Creek Road, west of town.

“We develop models and theories based on limited information,” he says, “so we when we have an earthquake that produces the kind of information that this one has, it’s just a great opportunity to learn.”

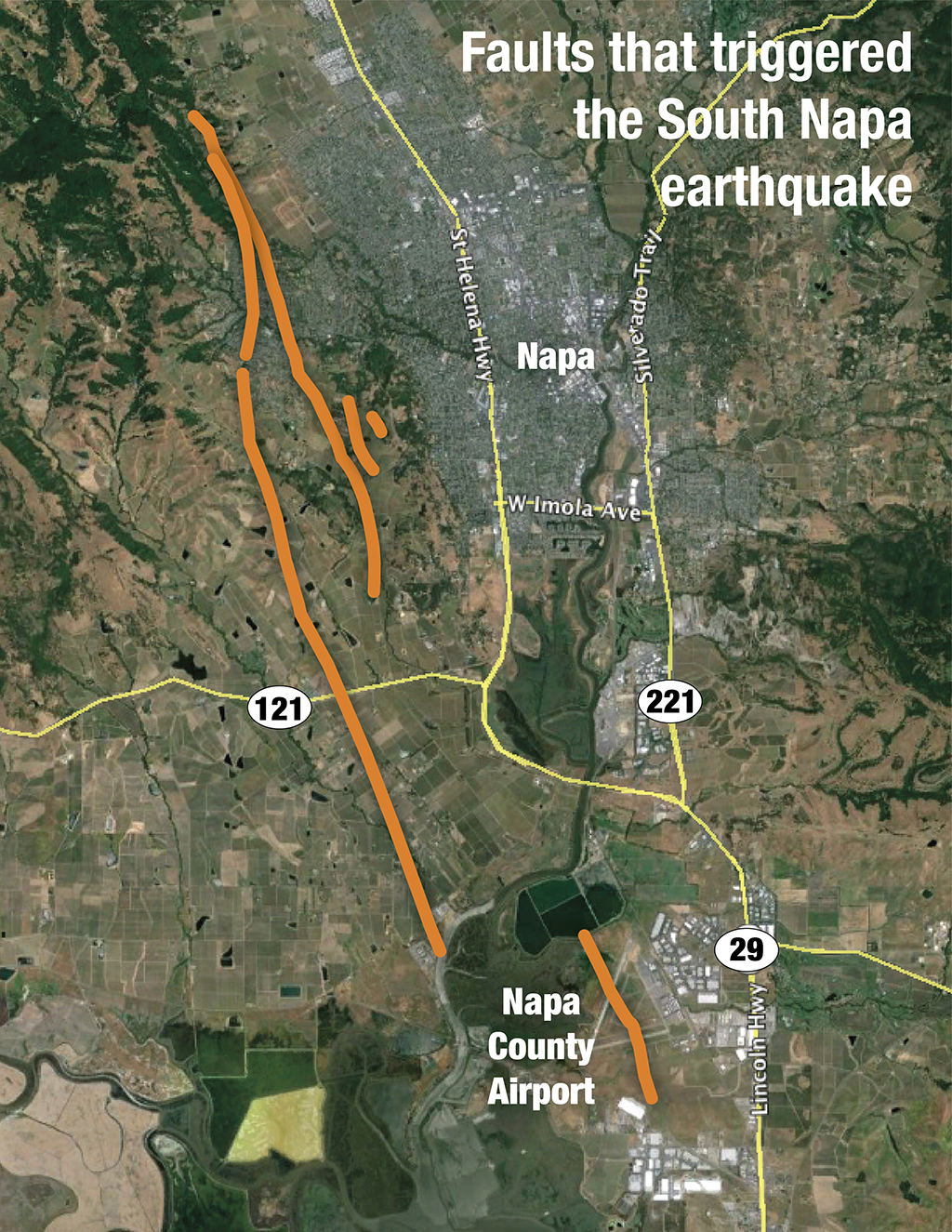

And there’s still a lot to learn about the West Napa Fault Zone, a jumble of faults that runs from near Vallejo, for at least 20 miles up the west side of the Napa Valley. It had been deceptively quiet, except for a 5-point quake in 2000.

Early deconstructions of the South Napa quake indicate that it broke about 6 miles deep, upward and to the northwest, along unnamed strands of the West Napa Fault.

Schwartz has been crisscrossing the valley for the U.S. Geological Survey, studying cracks in roads and driveways for evidence of lateral movement, or side-slip, where it’s clear that one side of the crack moved north and the other south, even if just a few centimeters — just like the jagged fissure that cuts through a west-side subdivision in Napa.

Kathy Ortiz remembers riding out the quake, the biggest that she can recall from her 65 years in Napa.

“It was unbelievable,” she recalled, days afterward. “My brain is still trying to take it all in.”

But Ortiz had no clue until daylight appeared that the quake had left a crack running completely across her street and under the homes on either side — a subtle displacement that geologists say mirrors the grinding along the strike-slip fault that broke right under her house. It turns out that Ortiz lives in the Brown’s Valley section of the West Napa Fault Zone, an area that had never been fully mapped.

In the video below, Schwartz explains why this narrow crack in a suburban street is a clue to the fault’s location beneath.

“The faults in this part of Napa Valley had been mapped as old faults, faults that may have moved in the last 130,000 years or 1.6 million years,” Schwartz explained. “But they weren’t mapped as ‘Holocene,’ or active.”

That’s about to change. But it’s not like Jules Verne’s “underground” classic, Journey to the Center of the Earth. Explorers can drop submersibles tens of thousands of feet to the ocean floor but there is no staircase through the Earth’s crust.

“The crust is complex,” Schwartz says. “And each one of these earthquakes gives us a little bit more insight into how it works, but we’ve got a long way to go.”

So far, a combination of ground sleuthing and interferometry, which measures changes in the landscape from satellite data and precise radar measurements from NASA aircraft, have allowed scientists to track the Napa quake’s suspect fault for at least 7 miles beyond where it was mapped before. Ultimately, the re-mapping of these faults will likely mean some changes in the seismic zoning of the Napa Valley, and some reconsideration of what can be built, where.

For Gareth Funning, the quake was like hitting the lottery. The geophysicist from UC Riverside had already been running a long-term study of ground movement in the valley when the earth moved. His network of precise GPS antennas will help create a model of the seismic events (literally) underlying the quake.

“We were up north measuring more things like this around Clear Lake when the earthquake happened,” Funning recalls.

He and his graduate assistant, Jerlyn Swiatlowski, hightailed it down to Napa to take fresh readings, tracking the movement of markers placed in the ground years ago as part of the National Geodetic Survey. Very precise GPS antennae — accurate to about 2 millimeters — placed over each marker, show that some of them moved up to 10 inches with the August 24th temblor. Funning says he’s using the data to model the underpinnings of the Napa quake and its ripple effects on the local geology.

“Those models allow us to then calculate the effect of this earthquake on all the other faults around this area,” Funning says, “and whether the stresses on them have changed as a result of this earthquake happening.”

Funning says it does appear that neighboring faults from Fairfield to Petaluma were “loaded” with some additional stress by this quake, which could increase the chances of them slipping. The Rodgers Creek fault, which slices from the Bay to Santa Rosa, has the potential for a magnitude-7 quake — bigger than the Loma Prieta quake that hit the Bay Area in 1989.

“We want to know whether an earthquake on another fault has become more likely because of this one,” Funning says.

A month after the quake, scientists are already gaining a better sense of the seismic potential underneath the wine country — but the picture is still coming together, and it’s hard to know exactly what it portends.

“Sometimes we see sequences of earthquakes over a period of decades and maybe that’s what’ll happen here,” Schwartz says. “We don’t know. But it should heighten the earthquake sensibilities of everyone in the Bay Area.”