You're Not Hallucinating. That's Just Squid Skin.

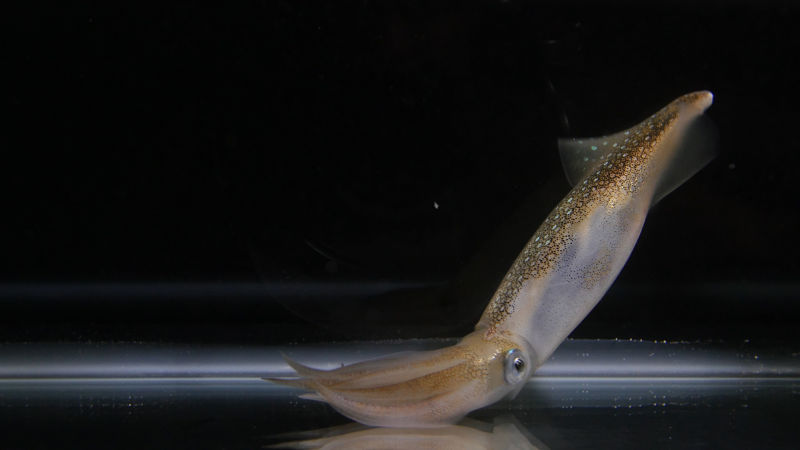

For an animal with such a humble name, market squid have a spectacularly hypnotic appearance. Streaks and waves of color flicker and radiate across their skin. Other creatures may posses the ability to change color, but squid and their relatives are without equal when it comes to controlling their appearance and new research may illuminate how they do it.

Octopuses, cuttlefish and squid belong to a class of animals referred to as cephalopods. These animals, widely regarded as the most intelligent of the invertebrates, use their color change abilities for both concealment and communication. Their ability to hide is critical to their survival since, with the exception of the nautiluses, these squishy and often delicious animals live without the protection of protective external shells.

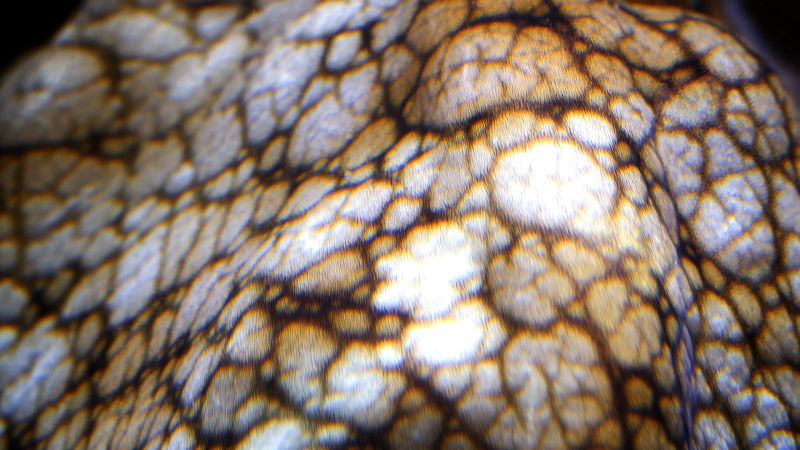

To actually control the color of their skin, cephalopods use tiny organs in their skin called chromatophores. Each tiny chromatophore is basically a sac filled with pigment. Minute muscles tug on the sac, spreading it wide and exposing the colored pigment to any light hitting the skin. When the muscles relax, the colored areas shrink back into tiny spots.

Because the system is based on the action of quick responding muscles, cephalopods are able to change colors almost instantly and can produce spectacularly intricate patterns to break up their outline.

Hannah Rosen, a PhD candidate at Stanford University’s Hopkins Marine Station in Pacific Grove, is studying how exactly these animals control this dramatic light show. Squid are notoriously difficult to keep in captivity, so the first step toward studying them is to to head out into Monterey Bay to catch some specimens.

Rosen isn’t the only one fishing for squid. But while the squid aboard most of the fishing boats in the bay will end up served as calamari, the squid Rosen catches may help explain the mystery of how these creatures control their color change.

Her research includes snipping a nerve that connects the brain to the chromatophores on one side of the squid’s body. When Rosen does this, the chromatophores on that side immediately relax and shrink to tiny spots, while the chromatophores on the intact side continue to flash normally. After a few days, some of the chromatophores on the paralyzed side began to move again, as if they were getting a signal from somewhere other than the squid’s brain. This phenomenon, Rosen says, is what fascinates her.

Rosen also tests how the fresh dead squid skin reacts to electric voltages when exposed to different pharmaceutical drugs in order to track down the neurological pathways involved.

While it’s still early to say, one possibility is that the skin itself is able to see and stimulate the chromatophores locally, bypassing the brain. A recent study at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Mass., indicates that cuttlefish skin has light-sensing cells. Further investigation may help researchers understand how much of the color change control comes from the brain and how much is controlled by the skin itself.

For more info, you can visit:

California Academy of Sciences – Color of Life Exhibit

Monterey Bay Aquarium – Tentacles Exhibit