There’s something buried in the Arctic soil that could have a huge effect on the future of our planet’s climate. Scientists from Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory have descended on Barrow, Alaska to study permafrost — soil that remains frozen throughout the seasons, often for thousands of years. They’re interested in permafrost because it has the potential to release an enormous amount of greenhouse gases in a short amount of time if rising temperatures cause the permafrost to thaw.

Nearly one quarter of the land in the Earth’s Northern Hemisphere is permafrost, and the decaying plant matter within it contains about twice as much carbon as is presently in the atmosphere.

Photo: Roy Kaltschmidt/LBNL

The Next Generation Ecosystem Experiment – Arctic, is a collaborative project between Lawrence Berkeley Lab and seven other institutions to study this ecosystem in incredible detail. The researchers began work in 2012, and plan to continue their research through 2022.

They aim to combine information from a wide range of techniques – from Electrical Resistance Tomography that measures the soil’s moisture, salinity and texture, to a kite outfitted with a camera that reveals the surface vegetation and topography. By bringing together a variety of techniques, they hope to learn all they can about this one specific location. The team plans to use the knowledge to create more accurate computer models of our planet’s climate, which will allow scientists to better understand how permafrost everywhere will react to changes in temperature.

“The combination of above and below ground geophysical imaging of the Arctic tundra has enabled us to, for the first time, ‘see’ complex interactions occurring between land surface, active layer, and permafrost processes that contribute to carbon cycling,” says Susan Hubbard, Director of the Earth Sciences Division at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

In order to predict how large swaths of permafrost will react to changing conditions, the researchers must learn exactly what the soils are made of — down to the microscopic level. They need to know where the permafrost is and how deep it goes. They need to know what minerals it contains, including how much water and gas, and what tiny organisms live there.

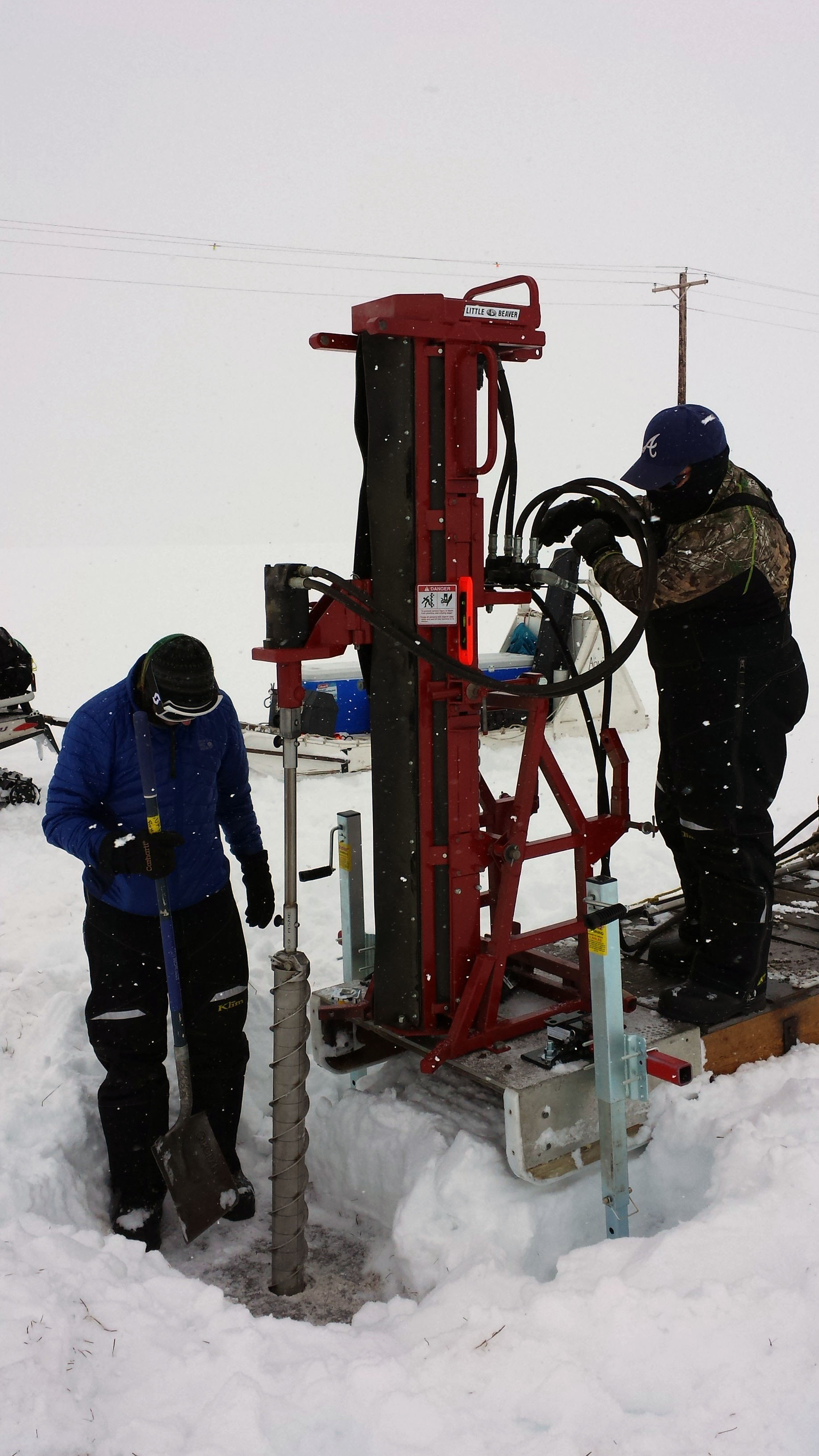

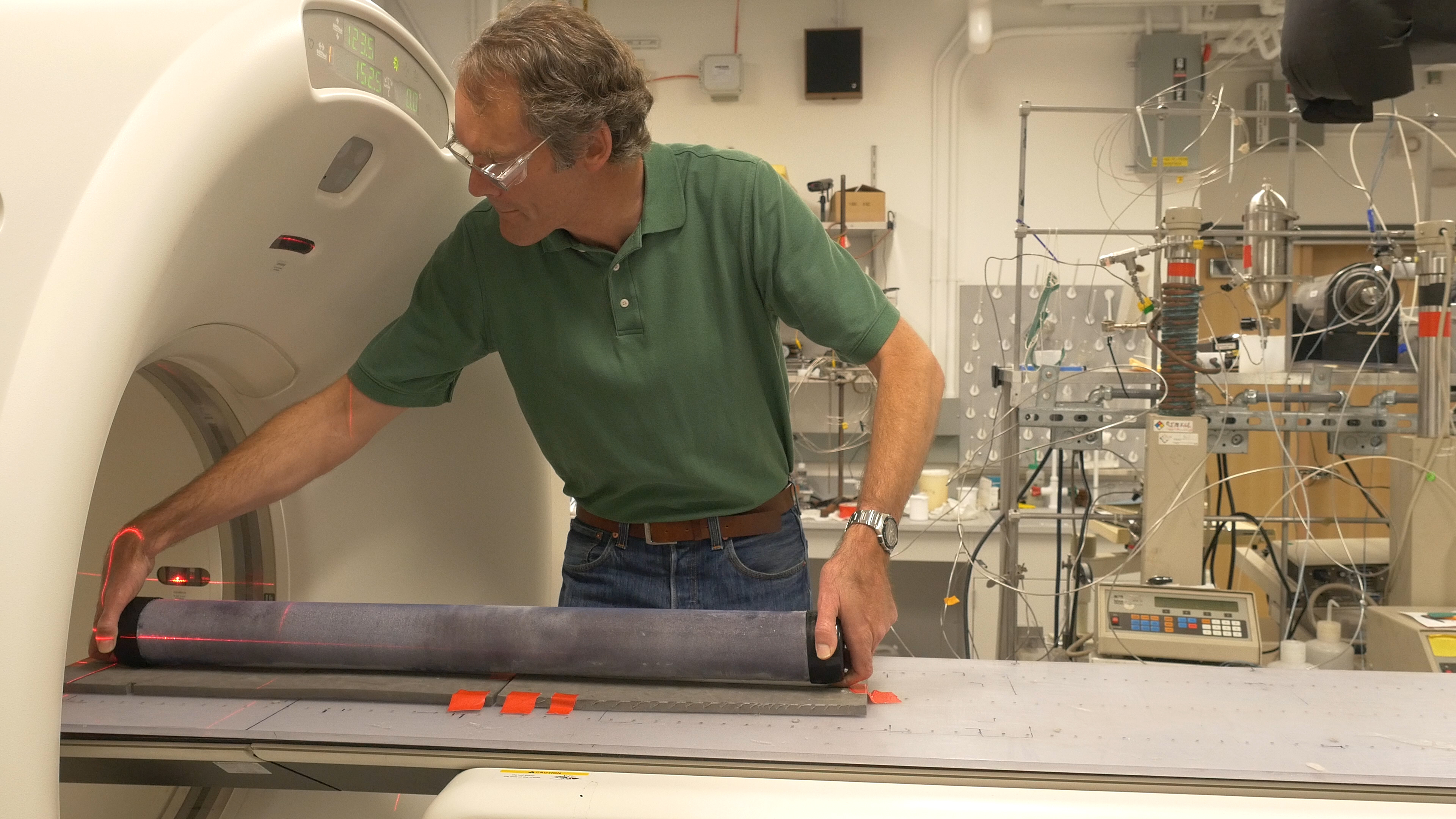

One aspect of the project requires the researchers to drill down from the surface and extract long solid cylinders of frozen soil. They ship the frozen samples back to research labs for a battery of tests. At Lawrence Berkeley Lab, they’re using a CT scanner, similar to those found in hospitals, to measure and examine the makeup of the cores, because different substances react differently to changing temperatures.

While the “active layer” near the soil’s surface can freeze each fall and thaw each summer, the permafrost layer further below may stay frozen for thousands of years. Within it lays the remnants of ancient plants and bacteria that have stayed dormant, trapped in the frozen soil. It also contains greenhouse gases, like carbon dioxide and methane, which are the waste products created by bacteria as they break down the dead plant matter buried in the soil. If the soil thaws, the ancient bacteria will get to work decomposing the plant matter and releasing greenhouse gases.

The extra greenhouse gases could trap heat in the atmosphere, which would in turn thaw more permafrost. This could result in a catastrophic feedback loop that would accelerate the warming of the planet. Another possibility is that a warming climate might create longer growing seasons in the summer, which would allow more plants to grow at the surface. As the plants grow, they could trap more carbon out of the atmosphere.

In addition to its vast size, the Arctic tundra is also extremely complex. The different geological features make it difficult to predict how the large swaths of land will react to warming, researchers say. Current models suggest that between 7 percent and 90 percent of permafrost may thaw by the year 2100. That wide range shows that scientists need to gain a more detailed understanding of the systems at play in order to achieve more precise predictions about the future.