California sea otters (Enhydra lutris) — the frolicking mascots of the coast who draw visitors to aquariums in droves and who float among the kelp beds just beyond the surf line — have the densest fur of any mammal on Earth.

With up to a million hairs per inch, the super-soft coats were once such a lure for hunters that they nearly led to the otters’ demise in the early 1900s. But now, the federally protected species is free to use its luxurious fur for one key purpose: to keep warm in the often chilly Pacific Ocean, particularly during winter months.

“They live in cold water, and it’s too cold for them,” says Heather Liwanag, a biologist who studied otter fur as part of her Ph.D. research at U.C. Santa Cruz.

Everywhere in the otter’s geographic range, she says, is outside their “thermal neutral zone.” This zone is the range of temperatures in which a mammal can live without expending energy to maintain its internal body temperature. So how do they do it? The same way you or I would—with a nice warm blanket. But theirs is a blanket of air.

“They’re using fur for insulation, but it’s not really the fur that’s insulating them,” says Liwanag, now an assistant professor of biology at Adelphi University in New York.

The true insulating power comes from a layer of air the fur keeps trapped next to their skin. Otter fur has two special properties that make it especially good at creating an insulating layer of air: It’s dense, and it’s spiky.

Otters fur is about 1,000 times more dense than human hair. But it wouldn’t do them any good if it were smooth and perfectly combed. Otters want their hair as tangled as possible, so that the air bubbles they blow into their pelts can’t get out. This is where the spiky aspect comes in handy.

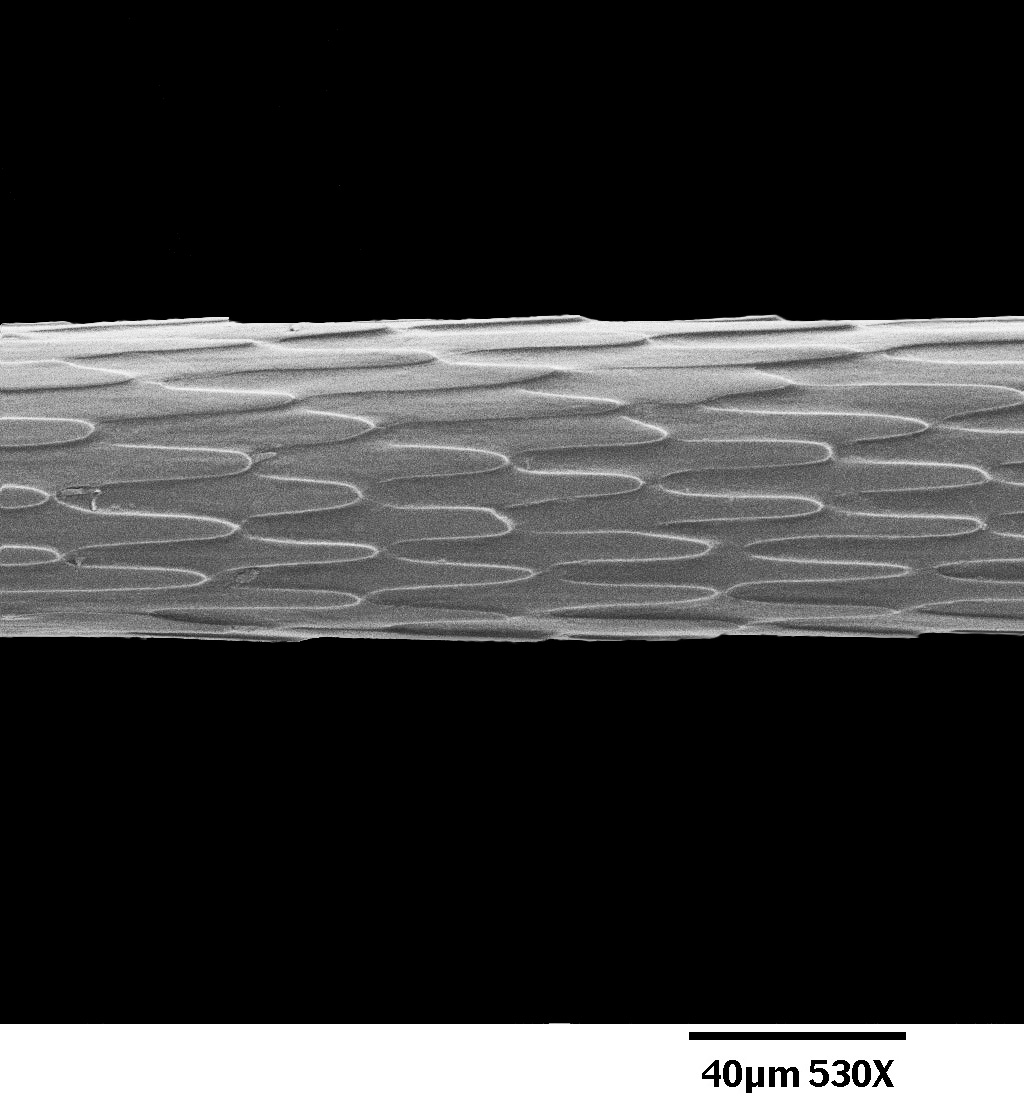

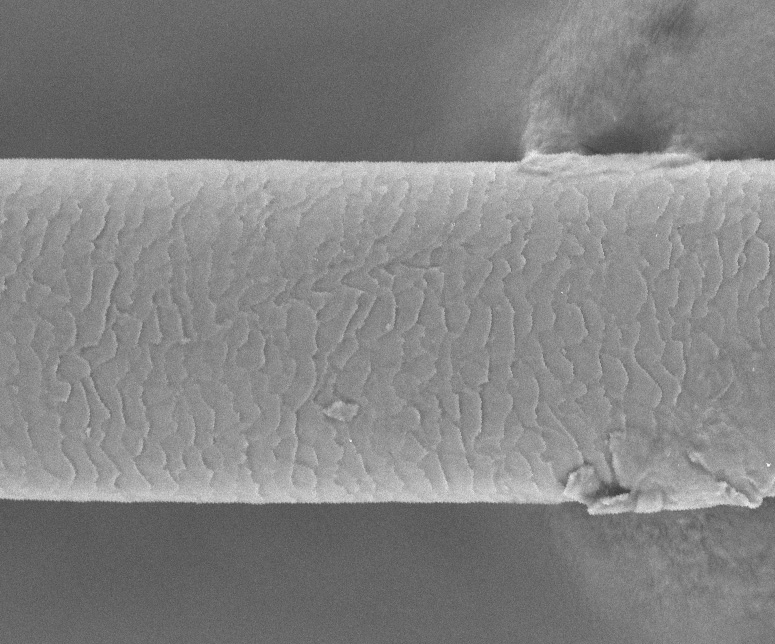

Otter pelts feel smooth and soft to us, but if you look at otter hair with a microscope you can see that it’s covered in tiny, geometric barbs. The barbs help the hair mat together so tightly that the fur near the otter’s body is almost completely dry. And keeping the animals dry is key to keeping them warm.

There are some disadvantages to the otter’s heating system. Because it relies on the trapped air, otters can’t dive too deep because high pressure forces the bubbles out. Also, the air makes them so buoyant they have to work hard to swim down. They sometimes even need to grab a rock or piece of kelp to help stay submerged.

Oil disrupts the sea otter fur’s ability to trap insulating air.The oiled section

shows bright red where the otter’s body heat is exposed. (California Department

of Fish and Wildlife)

Their unique use of air bubbles to stay insulated and warm is what makes oil spills so dangerous to otters. Oil can mat down otter fur and keep it from holding air. Without the insulation the otter is left unprotected from the frigid ocean water. It doesn’t take long for oiled otters to succumb to hypothermia and drown.

Many other marine mammals, including whales and sea lions, stay warm a different way — with layers of blubber.

Liwanag, in her thesis research that was published in 2012, compared the insulating powers of fur and blubber under different conditions. She wanted to learn more about how different species of mammals adapted to the marine environment to stay warm.

“Going in to this thesis, I fully expected blubber to be the better insulator,” she says, “because we see it arise multiple times, across different lineages.” But that wasn’t the case, and it turned out that fur—or really, air—is warmer, at least at shallow depths.

“If an otter were to use blubber to stay warm,” Liwanag says, “the amount of blubber it would need would be bigger than the otter.”