When geologists want to study an active earthquake fault, they often rely on a trenching study. They dig a long trench across the active trace of the fault, perhaps as much as 10 feet deep, or deeper if money and conditions allow. They brace the walls, if needed, to prevent cave-ins, then they climb down into the trench and carefully map its walls, looking for signs of past earthquakes and ground movement. (I gave more details in KQED Science last year.)

Geologists prefer to start this kind of work with a bulldozer. If that’s unfeasible, they’ll hire a backhoe instead. In a big, well-funded project they might get to use both.

But sometimes they have to revert to pre-mechanical means and dig with picks and shovels. This 19th-century technology, says one textbook, “is a valid option in places where power excavation equipment cannot be brought to a remote site, and abundant cheap labor is available.” Three recent examples show that the motivation of doing science can be powerful enough to get the job done.

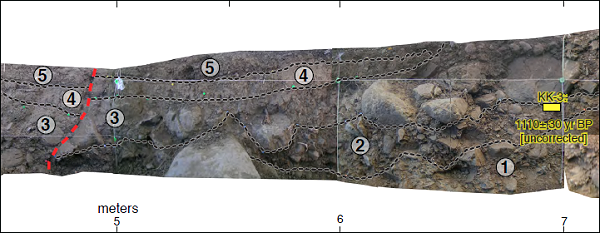

Last August, Humboldt State University researcher Sylvia Nicovich led a team of volunteers to a lump in the land south of Eureka, California, along the Van Duzen River, suspecting that it marks part of the Little Salmon fault. Her crew took two days to dig a trench across it 50 feet long and 4 feet deep, through a grove of newly planted saplings. “Rallying up a bunch of dirt lovers who enjoy being outside and physical was not a problem,” she said. “In fact, no one complained the whole two days of heavy digging, even with blisters on their hands and sunburns on their backs.”

A backhoe, even if the site permitted it, would have been more hassle, Nicovich said: “Lining up funds, land access in this delicate area, and all the necessary equipment for employing a backhoe turned out to be much more difficult.” And the scientific yield was good—the sides of the trench revealed a buried terrace of gravel.

Cores driven from the left end of the trench helped trace the gravel surface farther downward and show that it matched other evidence of uplift due to recent fault activity. Nicovich presented her results at a meeting in San Francisco last month.