Article by Mallory Pickett

Below the majestic trees and prehistoric ferns that grace California’s redwood forests lives a weird and slimy creature: the banana slug.

Named for their bright yellow color, banana slugs aren’t that different from the slugs you might try to keep out of your garden. They belong to the same family of animals, called gastropods, which have no spine and only one foot.

Banana slugs are important members of the redwood forest community, even if they aren’t the most exalted. They eat animal droppings, leaves and other detritus on the forest floor, and then generate waste that fertilizes new plants. Being slugs, they don’t move very quickly, and without a shell, they need other protection to keep themselves from becoming food and then fertilizer. Their main defense: slime.

slug was found in Henry Cowell Redwood State Park after a day of rain.

Slime refers to mucus—the same stuff that coats your nose and lungs—found on the outside of an animal’s body. Banana slug slime contains nasty chemicals that numb the tongue of any animal that attempts to nibble it, discouraging predators like raccoons, who have to go to the trouble of removing the slime if they want to eat the slug. But this is just one of many ways slugs depend on slime, and they use it for everything from locomotion to nutrition.

Slime can absorb up to 100 times its original weight in water. So it helps slugs, which are mostly water, stay moist. It’s also both a great lubricant and a sticky glue, so they can use it to glide over a razor blade or stick to a windowpane. Engineers are fascinated by these dual lubricant/adhesive properties, and would love to learn to make slug slime in the lab.

Christopher Viney is one of these engineers. He’s a materials engineer at the University of California, Merced, and a slime expert. Viney has spent years studying its chemical and physical properties, something very few scientists had done before. He and team harvested slime from dozens of banana slugs, which he says are “a very clean, reproducible source of mucus.” They discovered that the slime, which is chemically very similar to human mucus, has special properties that set it apart from other bodily fluids. For one thing, it’s not really a liquid, at least not a conventional one.

Viney discovered that mucus is a liquid crystal, which means it’s somewhere in between the liquid and solid state, as its molecules are more organized than a typical liquid but not as rigidly ordered as a solid. It’s composed of strands of glycoproteins — molecules in which a protein backbone is decorated with carbohydrate side chains — that are semi-ordered, like braided hair, instead of being tangled together randomly like a bowl of spaghetti.

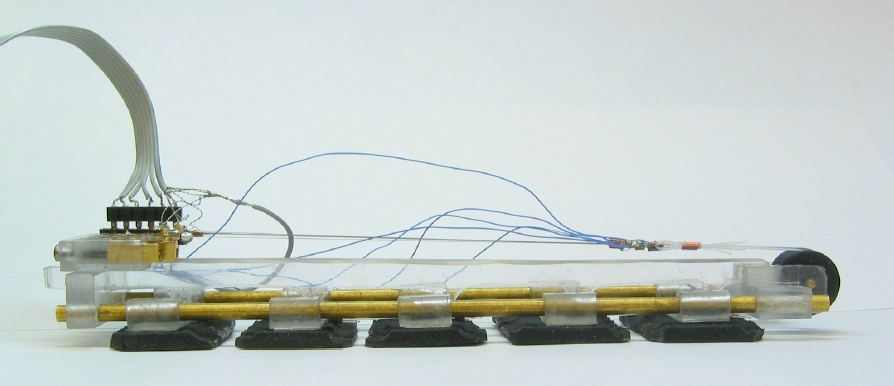

Viney has since moved on to studying spiders and silkworms, but many other engineers, biologists, and even medical doctors are still studying banana slugs. Engineers at MIT tried to copy the unique way slugs and snails move by building a “robo-snail,” which they hoped would be more stable and better able to traverse rough terrain than a robot that walks like a human or moves on wheels.

how gastropods like slugs and snails move, using foot pads that mimic gastropod foot muscles and synthetic slime.

The robo-snail has foot muscles and even synthetic slime. It can crawl over glass and up walls and ceilings, but it can’t quite achieve the mobility, grace and stickiness that come so effortlessly to slugs and snails. Janice Lai, a graduate student at Stanford University, used a special camera to observe every detail of a banana slug’s muscular movements and to model them, so that the next generation of robot snails and slugs can be a little bit closer to the real thing.

Janet Leonard, a staff scientist, and Brooke Wagner, a former graduate student, both of the University of California-Santa Cruz, have spent a lot of time closely observing banana slugs too, during the slug’s most intimate moments. They study banana slug mating: a long, slimy and occasionally carnivorous ritual (the slugs sometimes eat each other’s penises after mating, and no one really knows why).

Mating rituals are different for each of the three species of banana slugs, but some species spend over four hours on the process: two hours of courtship and two hours of repeated fertilization. After all this time in one place, the couple will be left in a big puddle of slime—which they eat.

“It’s important to recycle those nutrients,” Leonard says. “That time spent mating is expensive.”

The banana slug’s mating behavior, and its slime, have evolved over millions of years. After all this time, the banana slug is very well adapted to the redwood forest environment, scientists say.

Ilaria Mazzoleni at the Southern California School of Architecture, and biologist Shauna Price at UCLA want to capitalize on these millennia of evolution. They say they want to learn from some of the slug’s tricks to create a building that is equally well suited to the redwood environment. With a group of architecture students they built a prototype for a greenhouse with special silicone units that capture and release water, inspired by the banana slug’s mucus secretions.

Mazzoleni acknowledges that some people, including her own mother, find banana slugs “quite gross.” But she says architecture “is a functional art,” and the banana slug is “a great source of inspiration for that function.”