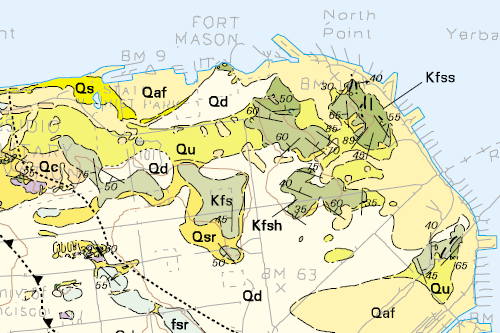

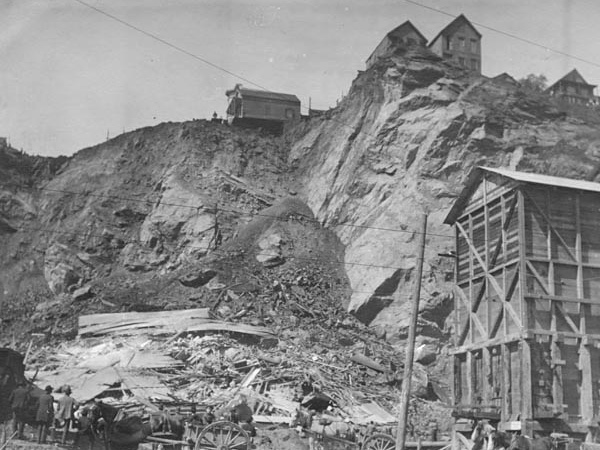

San Francisco is known for its hills, but before that touristic meme caught on, stone quarries were on course to remove some of them entirely. Twin Peaks had quarries; so did Bernal Heights; so did Diamond Heights; so did Point Lobos. There was a quarry in Golden Gate Park. But it all began at the nearest bedrock to the city’s original waterfront—Telegraph Hill.

A modern city needs rock as much as it needs water. Roadbeds and foundations are important uses that may come to mind today. As the Gold Rush began, San Francisco needed stone to build wharves and piers, stone to fill in the marshland and build more piers, and stone to use for ballast—rocks to weigh down the holds of ships after they were emptied of cargo. The pace of business was frantic, and regulations were few. Every possible hillside was pressed into service, and Telegraph Hill was the one that served the most.

The Vulcan Quarry was located on Francisco Street near Kearny Street. The George P. Wetmore Quarry was at the corner of Lombard and Montgomery streets. Other quarry faces are found just north of Broadway on the south side of the hill. But the biggest was the Gray Brothers quarry operation, headquartered on Sansome Street at Green Street, where a great vertical cut almost 200 feet high still stands, barely covered with vegetation.

By 1900 the ongoing damage alarmed not just the hill’s modest homeowners, but civic groups who wanted it preserved as a landmark. A member of the California Club told the Call on 3 January 1900 that the hill was “one of the natural and beautiful sites of San Francisco in addition to being closely identified with the early history of the city.” But quarry owner George Gray called it “very unsightly” and argued, among other things, that “if Telegraph Hill were cut down, residents on the east side of Russian Hill would have a magnificent marine view they do not now enjoy.” A decade later, the quarry was shut down and the city crept in. In 1927, Philo Farnsworth invented television in his Green Street lab on the quarry site.

A walk around the south, east and north sides of Telegraph Hill will give you many opportunities to peek at its innards. On the whole, it’s holding up well.

The sandstone is so massively bedded here that it crumbles less than your average former quarry. I think it’s fair to say, without offering a professional geologist’s opinion, that the next big earthquake will leave the hill mostly intact.