The initiative also includes new incentives for replacing lawns with drought-friendly landscaping, consumer rebates for water-saving appliances, and special assistance for residents whose wells have run dry.

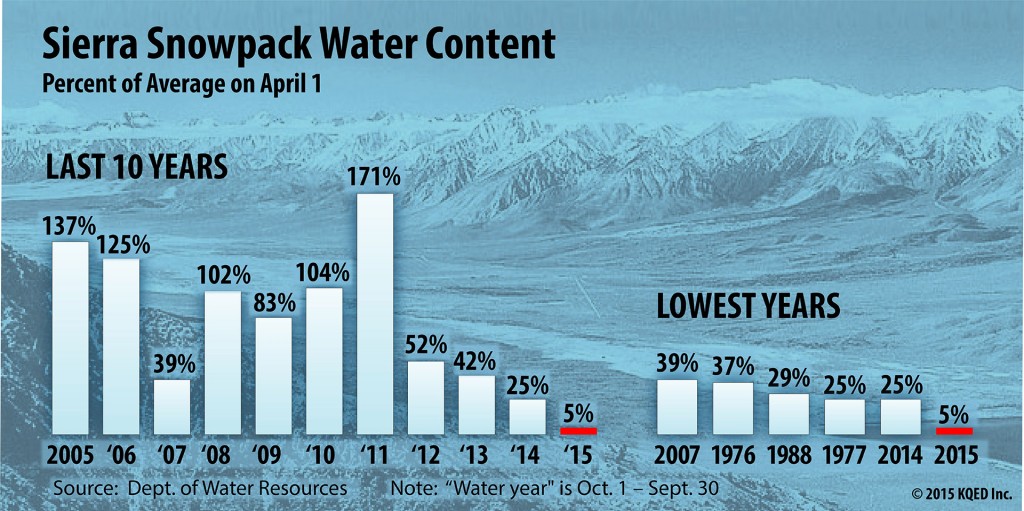

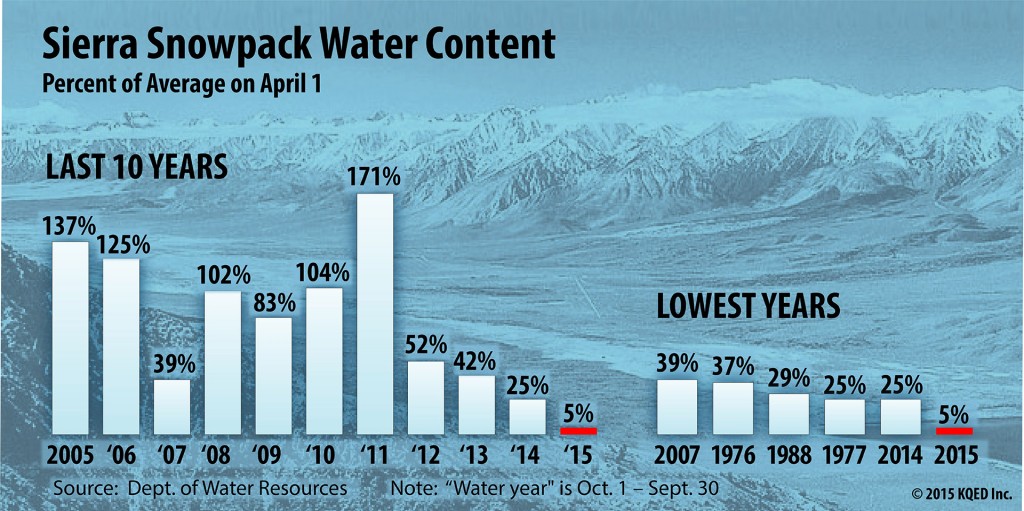

While the state’s Department of Water Resources does monthly snow surveys during the winter season, the April 1 survey is the benchmark for assessing the season as a whole. That’s when snowfall is reckoned to have peaked and the runoff season gets underway. Six percent on April 1 is essentially saying there’s next-to-nothing to show for an entire winter’s snow accumulation.

The snowpack has now seen four years of steady decline. 2013 was California’s driest year on record. 2014 was dry too, but also the warmest on record, which combined for a one-two punch to California’s water supply. In March, for example, both Sacramento and Redding logged average temperatures more than 10 degrees above normal, according to consulting meteorologist Jan Null of Golden Gate Weather Services.

The snowpack has now seen four years of steady decline. 2013 was California’s driest year on record. 2014 was dry too, but also the warmest on record, which combined for a one-two punch to California’s water supply. In March, for example, both Sacramento and Redding logged average temperatures more than 10 degrees above normal, according to consulting meteorologist Jan Null of Golden Gate Weather Services.

“There will be consequences,” says Mark Cowin, who heads DWR.

More than 400,000 acres of farmland were fallowed last year because of scarce water. Credible sources have estimated that figure could double this year.

“More impacts to farms where supplies will be shorted,” predicts Cowin, “more local communities where wells will run dry, and we’ll have to help assist them in some sort of emergency response, and more impacts to fish & wildlife, which is of course, very important.”

Groundwater resources will be stressed even more, as water-constrained farmers turn up the pumps to offset cuts in allocations from state and federal water projects.

Though Cowin hastens to add that “the vast majority of our citizens will not run out of water,” some already have, mostly in rural areas where wells have gone dry.

“I hope that this will continue to be a wake-up call for people that things are different,” says Lester Snow, a former DWR chief who now heads the non-partisan California Water Foundation.

“And not only is it gonna be bad this year but let’s not pretend that next year’s gonna be a lot better,” he added. “This drought has revealed fundamental weaknesses in our drought management system, and we need to start addressing those weaknesses.”

Other impacts from the paltry snowpack will be more subtle, such as the loss of hydroelectric power. Less runoff coming down the hill, turning hydropower turbines means that utilities have to replace the electricity, which they usually do with natural gas-fired power plants. That wields a bigger carbon footprint and adds to Californians’ electric bills — $1.4 billion since 2012, by one estimate.