This post was originally published in 2015.

One afternoon in the spring of 1914, Mount Lassen awoke with a cough, the sudden burst of steam and ash from its 10,500-foot summit startling residents of the northernmost Central Valley and surrounding mountains.

Burt McKenzie, a cattleman in the high meadows nearby, telephoned a Forest Service ranger and told him the mountain was “blowing up.” The ranger checked it out on snowshoes the next day. Soon he and other climbers confirmed that the explosion had left a smoking crater about 100 by 350 feet in size, ringed with fresh volcanic ash and puffing sulfurous fumes.

Similar activity continued for a year: small explosions and mostly harmless clouds of steam and ash. Newspapers entertained the country’s readers with the newest sensation from colorful California. Local photographers staked out the good spots and sold their images to all and sundry.

Since that time, geologists have learned to discount those historic newspaper stories and prize those historic photographs instead. Michael Clynne, who has studied Lassen for the U.S. Geological Survey since 1975, told an audience last month that about 1,000 different photographs survive showing Lassen in action. With their help and lots of scientific sleuthing, we have made sense of California’s first and only volcanic eruption since statehood.

Mount Lassen was awake for just over three years, from that first blowout in May 1914 until a final burp in June 1917. It climaxed in a proper eruption, with red-hot lava and everything, over the four days of May 19-22, 1915 — 100 years ago this week.

The first year’s explosions were steam blowouts, triggered when rising magma met groundwater and flashed it into vapor. Geologists call these phreatic (“free-AT-ic”) events. From 1914 through the following spring there were almost 200 phreatic explosions, practically guaranteeing visitors the opportunity to see one.

The active crater slowly grew to about 1,000 feet. On May 14, 1915, it was seen to glow as real live lava rose up and congealed into a large dome. On May 19, a new crater opened with an explosion, shattering the dome and showering its glowing guts onto the northeast flank of Mount Lassen, which was 30 feet deep in snow after the El Niño winter of 1914-15.

That night and the next day there ensued a triple-whammy of damage. First an avalanche of snow and lava roared 4 miles down the mountainside, snapping off trees at the stump.

As the lava ended, the snow melted and started a large mudflow, or as geologists call it, a lahar (“la-HAR”). The lahar plowed 11 miles farther down the valley of Lost Creek, tearing out trees by the roots.

When the mudflow stopped, all of that meltwater seeped out in a large, muddy flood that swept over several ranch houses on its way to the Pit River, where it caused a massive fish kill. The ranchers escaped with their lives.

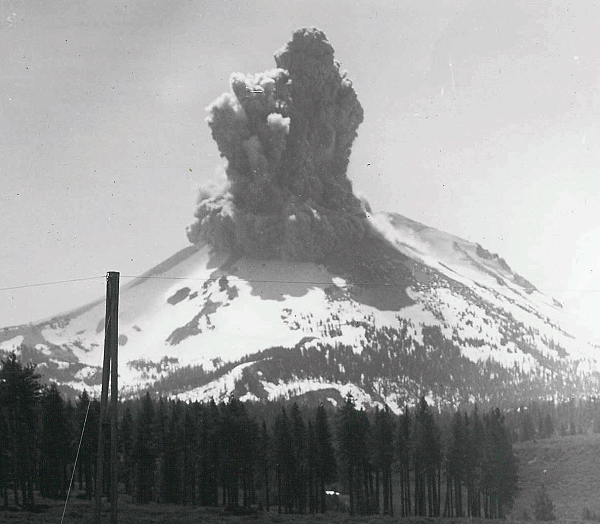

Then, on the afternoon of May 22, a classic-style eruption opened a new crater near the summit. A high column of ash formed a mushroom cloud, seen as far away as Eureka and Sacramento. Winds carried the high ash eastward in amounts that people noticed all the way across Nevada.

The lower part of the eruption cloud descended upon Lassen’s northeast flank and started another triple-whammy, causing even greater damage to the forests, rivers, and ranches. First this time was a pyroclastic flow – a fiery avalanche of pulverized rock. For all the fearful spectacle, no one died that week.

After the climax of May 22, Lassen resumed its phreatic explosions, which continued for two more years and then sputtered out. The boiling mudpots and vapor-spewing fumaroles south of the volcano, already a tourist attraction in 1914, continued unchanged. And so it’s been ever since, the forest slowly returning to the Devastated Area.

Mount Lassen isn’t like the other Cascade volcanoes. The range is famous for its high, snow-capped peaks, from Shasta to Rainier and on up to Canada, but it includes a wide variety of volcano types.

The Lassen area is at the very southern end of the chain, where plate tectonic movements are gradually snuffing out the deep source of its vitality. There, magmas that rise into the Earth’s crust are made of stickier stuff than the typical Cascade recipe, and they also tend to burst out in a scattershot pattern rather than in one big vent.

In the Lassen area, short-lived eruptive episodes build lava domes and smaller structures. Lassen itself is a particularly large dome, one of the world’s biggest. It formed 27,000 years ago in a brief spasm of activity, and, to judge from the uniform age of its lava rocks, it had been inactive ever since.

Given that geologic history, the 20th century eruption at Lassen looks like an oddity rather than a pattern — perhaps a mere coincidence. Geologists do not think Lassen is a Shasta in the making.

Nevertheless, Lassen’s most recent eruption will likely not be its last.

“The Lassen volcanic center is still active,” Clynne says, “and it will erupt again. It’s only a matter of time.”

The magma chamber is still there, but the molten rock is so choked with mineral crystals it can barely flow. Only a pulse of fresh magma from below could melt it a little and enable a new eruption.

Using seismographs, tiltmeters, satellite observations and other techniques, we can now monitor the space beneath the magma chamber and watch for new infusions of material. Lassen’s next eruptive episode may not happen at Mount Lassen, but whenever and wherever it starts, it won’t take us by surprise again.