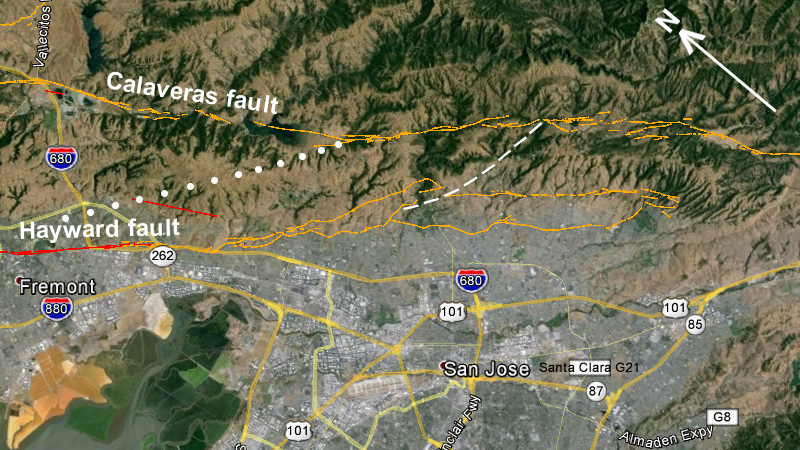

Ask Bay Area seismologists their most worrisome earthquake scenario, and many will say it’s not a repeat of the great San Francisco quake of 1906. They don’t think that’s likely. Instead, it’s a possibility considered unthinkable not long ago. That would be a rupture that tears the full length of the Hayward fault, between Pinole and Fremont, then jumps past the end to the next fault.

The next fault to the north is the Rodgers Creek fault, running from San Pablo Bay into Sonoma County. Scientists have made scenarios for big quakes on the combined Hayward-Rodgers Creek. The damage from shaking, fires and landslides would exceed $200 billion.

The next fault to the south is the Calaveras fault, running from east of San Jose past Hollister. But that combination hasn’t been modeled. Until a few years ago nobody thought this deadly combo was likely.

Where the two faults merge, geologists have mapped a complex snarl of ground fractures. The faults don’t appear to line up together well, which means they would prevent any rupture from pushing through. But our maps have been too imprecise to be certain.

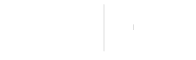

Now UC Berkeley seismologist Estelle Chaussard has assembled the clearest picture yet of the Hayward-Calaveras merge. Her model, just published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, simplifies the intersection while showing that deep underground, the two faults line up dangerously straight together. But the same model helps us to simulate and plan for the hazard of a combined fault rupture.

Deep underground where earthquakes actually take place, the two faults join in a smooth line. But when geologists map the fault traces in this area – if they can even see them in the underbrush and landslide scars – the maps look as untidy as the edges of a torn-up newspaper. Moreover, they can’t tell which of the various fault traces is currently active.