The Sex Lives of Christmas Trees

It’s the time of year when people start inviting pine, fir and spruce trees into their homes, and wreaths and pine cones take center stage. But while pine cones may seem a familiar trapping of the holiday season to most of us, for Bruce Baldwin, they tell an ancient story, millions of years old, of evolution, competition and reproduction.

Baldwin is a plant biologist in the Integrative Biology Department of the University of California, Berkeley. He’s also curator of the university’s Jepson Herbarium, a collection of California plants used for research and archival purposes. In addition to the pressed and dried plants, the herbarium’s collections also include a variety of cones from around the state, including some from the Coulter Pine, which boasts the largest cones of any pine tree in the world.

Pine cones aren’t just for decoration, Baldwin said. They are the reproductive organs of conifers, an ancient group of seed-bearing plants.

“There are two different types of cones,” said Baldwin, “a lot of people don’t realize that. There’s seed cones and pollen cones. The pollen cones are relatively tiny. The seed cone gets to be much larger and takes three years to develop and release seeds so you can often see pine cones of three different stages of development on a single tree.”

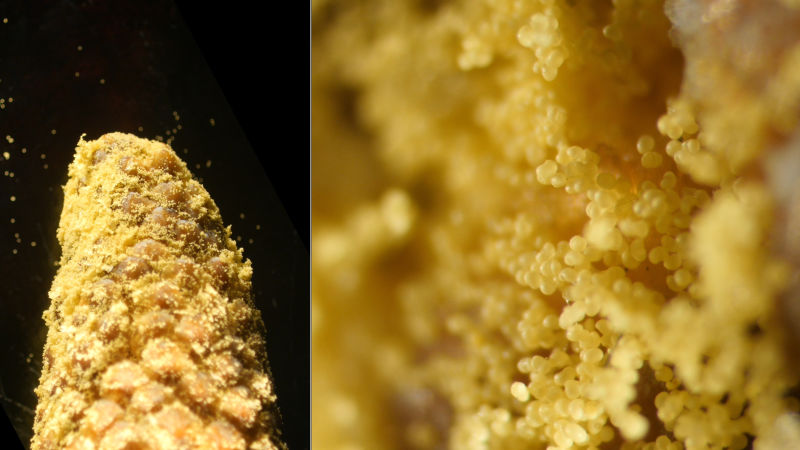

What most people recognize as a pine cone is typically the female seed cone. This structure keeps the immature seeds safe, nestled between protective scales.

But early in their development, the scales open slightly for a short time to grant access to wind-borne pollen released from smaller pollen cones. Conifers are mostly wind pollinators, broadcasting huge quantities of male gametes into the air during summer months. The pollen can be seen when it settles on parked cars and windowsills as a fine yellow powder.

After receiving the pollen, the female cones close back up until the seeds are fertilized and mature. Once they are, the scales reopen allowing the wind to disperse the winged seeds. Other species rely on birds or mammals to distribute their next generation.

In some forests, like the closed-cone pine forests of California, mature cones may stay closed for decades. Species like the bishop pine are serotinous, meaning that they only open when exposed to the heat of a forest fire. The trees are able to wait until the fire has reduced the competition for light and provided a much-needed boost in nutrients to the soil before even attempting to send their seeds out to set root.

Conifers are some of the oldest plants in the forest. And they were once much more diverse than they are today. But since the evolution of flowering plants, their diversity has plummeted. Today only about 0.3 percent of all the species of seed plants have cones. Flowering plants have taken over most of the warmer, wetter habitats, pushing out the conifers. But why?

“Flowering plants reproduce much faster. Everything is sped up in their reproduction,” explained Baldwin. “And when you evolve the fruit you evolve a lot of different ways of dispersing the seeds.”

Enlisting the help of animals to carry off their seeds may help give flowering a reproductive advantage, he said. Conifers mostly distribute their seeds by wind.

While they no longer dominate the tropical areas of the globe the way they once did, conifers do cover much of the Northern Hemisphere’s forest ecosystems.

“They’re less successful than they were at one time, but still major players as far as seed plants go” said Baldwin. “They do great at higher latitudes and higher altitudes, though there are a few exceptions. But by-and-large they are more successful in areas that are cooler, dryer and with poorer soils”

Flowering plants are able to out-reproduce conifers in the areas which have more ideal temperatures, and moisture levels. Conifers are thus relegated to areas where flowering plants cannot survive well. Conifers are able to exist in these areas because their anatomy allows them to resist damage caused by freezing, and extreme dryness. Conifers also pack their leaves with terpenoids, which are compounds responsible for the pine smell that allows the trees to resist decay and hungry herbivores.

While they may no longer be as diverse as they once were, the tallest (coast redwood), most massive (giant sequoia) and oldest living (bristlecone pine) individual organisms in the world are all conifers. While they may not be as flashy as their flowering cousins, cones are still able to hold their own, particularly around Christmas time.

You can check out the conifer collections at the University of California, Berkeley Jepson Herbarium.

Or take a stroll through Tilden Regional Parks Botanic Garden to see a variety of California conifers.