Listen to the Story:

Scientists Track Undersea Noise Pollution as Ship Traffic Swells

Scientists Track Undersea Noise Pollution as Ship Traffic Swells

Undersea sounds from Monterey Bay provided by Dave Cade and Hopkins Marine Station.

UPDATED 6/1/16: The Obama Administration on Wednesday released its first-ever comprehensive strategy for reducing undersea noise pollution.

Noise is becoming ever more “pervasive” in the ocean, says Michael Jasny, who directs the Marine Mammal Protection Project for the Natural Resources Defense Council. He says ocean noise from shipping, naval sonar and industrial operations has been doubling every ten years for several decades, interfering with marine animals’ ability to find food and reproduce.

“This is a problem that is intensifying,’” he says. “The science has made clear that it has to be dealt with.”

Jason says the patchwork of laws governing ocean noise have not been joined by a single strategy. While NOAA’s 140-page plan stops short of establishing any actual rules, environmentalists say it’s a good start toward “concrete action” to muffle the ocean soundscape.

The draft “roadmap” could eventually lead to actions such as placing speed limits on merchant ships in some areas, or re-drawing shipping lanes to minimize impacts on marine life.

ORIGINAL POST:

When one of the world’s largest container ships passed under the Golden Gate Bridge on New Year’s Eve, it raised the curtain on a new era for West Coast container ports — and raised new anxiety for marine biologists.

Scientists have long been concerned about the impacts of noise pollution on undersea ecosystems. A wide variety of marine animals, from whales to snapping shrimp, depend on sound to navigate, communicate, and even survive.

“At a very basic level, we know that these animals use sound as we use light,” says Brandon Southall, a marine consultant and research associate at the University of California, Santa Cruz. “It’s their fundamental essential mode of communication.”

While environmentalists have fought epic battles with the U.S. Navy over interference from sonar, Southall says the growth of commercial shipping poses by far the biggest threat to the undersea soundscape, from the noise ships generate simply by moving through the water.

With an overall length of 1,300 feet, the ULCS (Ultra-Large Container Ship) Benjamin Franklin is the biggest ship ever to call at a North American port — 200 feet longer than the Navy’s newest, biggest aircraft carriers.

When fully loaded, the Franklin has a draft of 52 feet — it’s like dragging a 5-story building along underwater. That takes giant propellers and a huge amount of power to move. And all of that generates low-frequency noise below the surface.

“Other things in the ocean make sound,” says Southall, “but shipping is the overwhelmingly dominant component of the noise that people put into the ocean in places like San Francisco Bay here, where you have all the ships coming in and out.”

The ship’s operators say the Franklin is designed to be more than compliant with new international guidelines for minimizing ship noise below the water line. But the guidelines are voluntary, and there’s no assurance that other shippers will follow suit, especially in retrofitting older ships.

According to Lloyd’s Register, total tonnage of the global merchant shipping fleet is expected to double by 2030 (v. 2010). That would mean more ships and bigger ships. The number of large container ships could multiply six times, driven by growing populations, rising consumerism and increased global trade.

In response, scientists are deploying a network of undersea listening stations to develop a more complete “picture” of ocean soundscapes and how they’re changing.

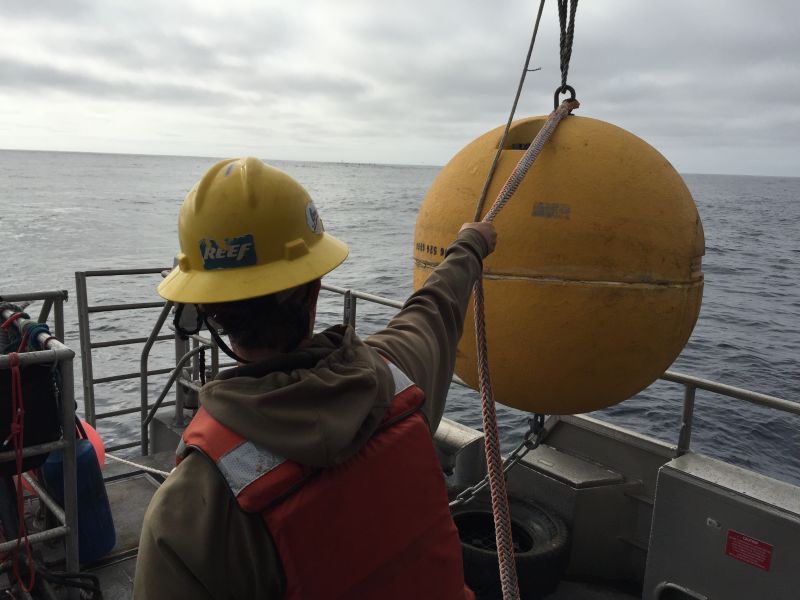

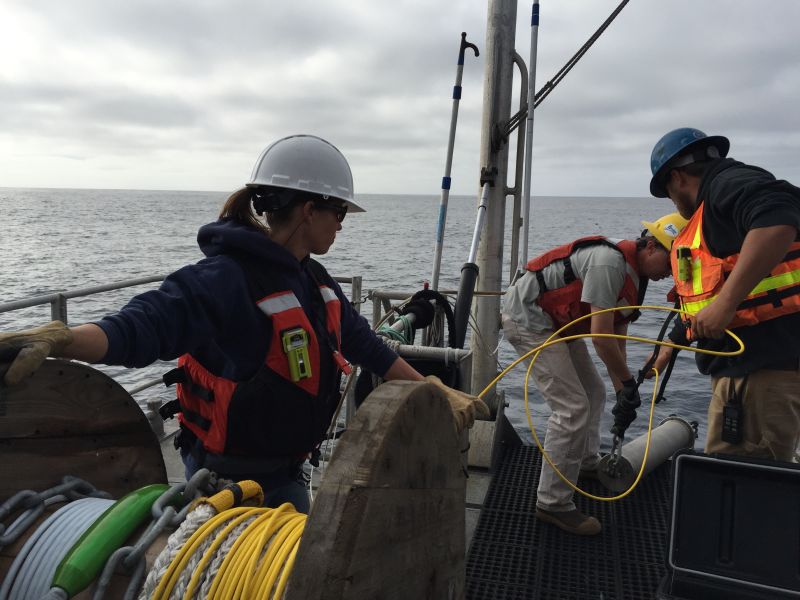

“There’s a lot of noise in the ocean and the oceans have been getting noisier,” researcher Danielle Lipski told me as the NOAA research vessel R/V Fulmar was about to cast off from Bodega Bay in October.

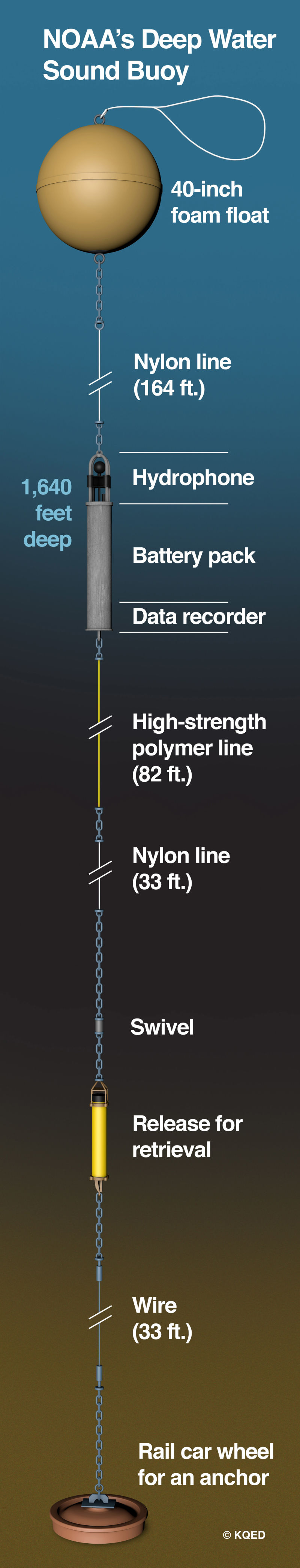

Lipski’s mission on that day was to deploy the newest in a network of underwater listening devices, this one about 20 miles off of Pt. Reyes.

“We know that there are ships and we know that there are whales,” she said, “but we don’t really understand the soundscape there.”

Lipski says sound — especially in the low-frequency range where whales vocalize — can travel hundreds or even thousands of kilometers underwater, depending on a variety of factors such as the contours of the sea floor, water salinity and even temperature.

Researchers at NOAA’s Pacific Marine Environmental Lab hope this undersea “surround sound” will reveal, among other things, how much noise pollution is being generated by shipping lanes that cut through the Cordell Bank National Marine Sanctuary.

“From that I think we’ll get a pretty good idea of how that sound is affecting the habitat quality of the animals that are in the sanctuary,” Lipski said.

Answers won’t come quickly. The listening station, anchored to the sea floor in more than 1,600 feet of water, cannot transmit, so it will continue recording sounds for two years. Only then will scientists retrieve the hydrophone and begin to analyze what they’ve got.

“Having two years’ worth of data’s gonna be a really rich data set for us to understand the types of sounds that change seasonally and year-to-year,” Lipski told me.

And then, scientists can make recommendations for things like where to expand shipping lanes — and where not to — and fine-tune new international guidelines for making the ships themselves quieter.

Meanwhile, things continue to amp up under the waves. From a whale’s perspective, Southall likens it to living in a city undergoing rapid growth.

“He’s in a place that is loud and dynamic but it didn’t have this whole component of ships, boats, echo sounders — you know, just human presence — in the lifespan of some of these 150-year-old animals,” Southall said. “Their whole environment has gone from a rural area to a busy city, if they live near shipping lanes.”