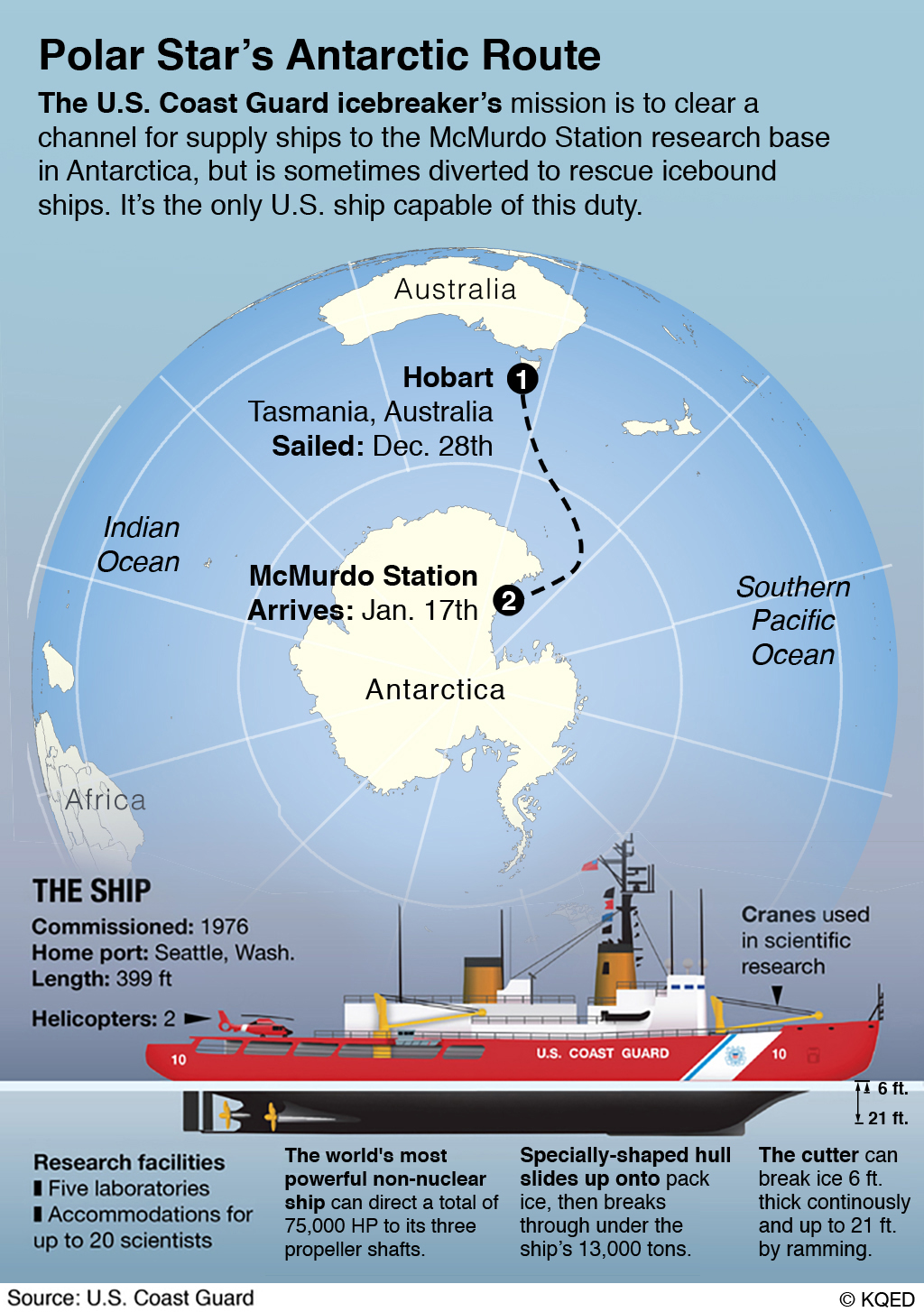

The fifth in a series of dispatches from freelance writer Brandon Reynolds aboard the USCG icebreaker Polar Star, on its annual resupply mission to the research base, McMurdo Station. It’s a critical task imperiled by the nation’s aging, shrinking fleet of ice-breaking ships.

The plan was this: groom the channel; spend a few days at McMurdo Station; escort a supply ship and a fuel tanker in; go north to Marble Point to refuel a National Science Foundation depot; wander across the arc of the continent and then dart north across the chaotic Southern Ocean and up the coast of South America to Valparaiso and points north.

But if there’s one thing I’ve learned on this ship, it’s that plans are suggestions and suggestions are dreams and dreams here are more familiar than reality. Things change at a moment’s notice. Mostly by breaking.

There are arcane equations that affect the ship, dealing with power output, weight distribution, atmospheric behavior, celestial navigation, on and on. There is only one that really means anything to the average dim-but-curious writer, and that’s the relationship between cutting a channel through the ice and the damage it causes; in other words, the ratio of breaking-in to breaking down.

The ice is, in scientific terms, absolute hell on the ship. Polar Star breaks in a variety of ways, and that delays the grooming of the channel, the only way that supply ships can get in. So when we’re back underway we speed along to the next breakdown. Are these critical breakdowns? They’re serious enough. Most of them are, strictly speaking, mission-enders — for a few hours. Then we’re on our way again.

What’s happening here that keeps the engineering department busy with repairs is a living example of the paradox of the implacable force against the immovable object. Polar Star is the last working heavy icebreaker in the U.S. fleet, and with 75,000 horsepower, it’s billed as the “most powerful non-nuclear icebreaker in the world.” The bow is nearly two inches thick, made of a special steel alloy that’s resistant to the cold and — more than 40 years after the keel was laid — no longer made in the United States. For durability, the frames (the ship’s “ribs”) are about six inches closer together than normal. The football-shaped bow allows the ship to slide (or grind, as it were) up onto the ice like an aggressive leopard seal and break through it. That takes a lot of power.

Most of the time, Polar Star runs on six Alco 251 diesel-electric generators. These are train locomotive engines, but they’re also used for icebreakers and nuclear power plant backups. They even make a satisfying chugga-chug chugga-chug, which is quite soothing when we’re out at sea. (During what qualifies as night during the austral summer, I lie in my “rack” and listen to the sound of distant trains along with the foamy hiss of the waves against the bow, a real surf ’n’ turf for the senses.)